Read The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine Online

Authors: Miko Peled

Tags: #BIO010000

The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine (10 page)

A close friend of my father’s, Issam Sartawi was a close confidant of Yasser Arafat and the PLO’s representative to Paris.

In an article he published in 1977, my father described in great detail both that first meeting with Sartawi and his own thoughts immediately before, and during, the meeting.

8

(When the article was published, Sartawi’s identity had not yet been made public, so he never mentioned him by name.) “How does one feel when one is about to meet his enemy?” my father asked.

He continued,

As I recall I was sitting in a comfortable armchair trying without success to read an article in

Le Monde

when the doorbell rang and two men entered. These were the two men for whom I had made the trip to Paris.

My role was relatively easy. The story of my people since the return to our homeland began is etched in my memory…

As my father saw it, the main question was this: “Will we be allowed to live our lives in peace and security… and be masters of our own destiny? Anyone who allows us to do this is a friend. Is the man with whom I am speaking willing to be our friend?” He also asked, “Can reality be transformed?” His answer there: “Anyone who does not believe it can is depriving himself of the great powers that nature has bestowed on mankind.”

Over the years, my father met with Sartawi in various locations all over Europe and North Africa—they spent time in Palma De Majorca off the coast of Spain, in Morocco, and in Tunis. The late Austrian Chancellor Bruno Kreisky, who was Jewish, facilitated many of these meetings, as did Landrum Bolling, a Quaker and former President of Earlham College in Indiana, who also became a good friend of my father’s. Landrum, a lifelong devoted peace activist, told me once about the time he and Chancellor Kreisky were with my father and Issam in Majorca. He and Kreisky stayed behind and let the other two walk along a secluded beach resort, deep in conversation. “If it was left up to these two men,” Landrum said to the Austrian Chancellor, “this conflict would be resolved immediately.” Kreisky agreed.

Before leaving for these meetings my father would say, “I will be away for a few days, I can’t talk about it but don’t be alarmed.” My mother worried sick until he was safely home. As we sat together late one night my father told me about a meeting at a remote resort in North Africa. “It was luxurious beyond imagination,” he said, “and miles from anywhere. Issam wanted to reassure me that we were safe, and he said there was no way anyone could possibly know that we were here.” He paused before getting to the main point of his story. “I looked around and pointed out the beautiful young receptionist. ‘Do you know for a fact that she does not work for the Mossad?’ I asked him.” My father took nothing for granted, and he knew just how far the arm of the Israeli intelligence could reach.

The contacts between members of the council and the PLO were largely kept secret, as few Israelis could comprehend the idea of talking with the

Ashaf

, and many Palestinians were fiercely opposed to a dialogue with Zionist Israelis. Over the years, Issam and his wife, Dr. Widad Sartawi, developed a personal friendship with my father and mother. Many years later, when my eldest son Eitan was 10, he and I—along with my mother and my sister Nurit and other family members— spent a memorable time with Widad and her family at her home in Paris.

In 1977, Israeli Television set up a roundtable discussion with the entire general staff of 1967—on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the war. The roundtable was held on a news program called “Moked,” and was later featured in the excellent documentary by Ilan Ziv that came out in 2007 called

Six Days in June

.

At one point, my father remarked that he did not recall ever hearing or seeing a directive from the cabinet to take the West Bank. It was the first time that I heard him criticize the IDF commander’s decision to take the West Bank without first seeking cabinet approval. “It had always been considered an important strategic directive to avoid conquering areas that were heavily populated, he said, “Taking the West Bank with its Arab population was a clear reversal of this principle, and I don’t recall ever hearing or seeing such a directive come down from the Israeli government.”

As he was saying this, the camera began pulling back to show the faces of the others around the table. Their unease at his words was obvious. Not only was my father reminding everyone that the West Bank and the Golan Heights were taken without cabinet approval, an act that in the past he had defended, but he was now

pointing out that the generals themselves reversed an important strategic directive without proper authority.

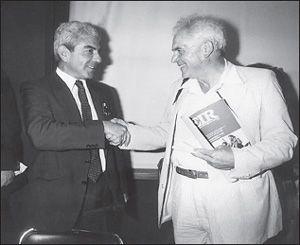

Israeli generals 10 years after the war.

For his leftist politics, my father received occasional death threats and was sometime accused of treason by extremist Jewish groups, most of whom had not served a single day in uniform. He would report these to the police and although he did not seem troubled, he always slept with a loaded pistol by his bed. At one point word got out that there had been a death threat made, and reporters called to interview him on Israeli radio. “Are you afraid for your life, sir?” the reporter asked.

His response was as cool and rational as ever: “The incident was reported to the police, and I have every confidence that they will deal with it appropriately.”

“I understand sir, but, General Peled, my question is, are you afraid for your life?”

“The police took a report, and I am sure they will know what to do.”

“Yes sir, I understand you have faith in our police force, but are you afraid?”

“I have nothing more to add.”

He refused to say any more than that, and he ended the interview. In a way it was not unlike his attitude toward building a bomb shelter for our home. If something made sense to him, he would not allow emotions like fear get in the way of good reason, and that was the end of the conversation.

In hindsight, I think he was right to answer the way he did in so far as he did not want to give in to the extensive myth that there was some horrible, pervasive threat and that we all had to live in fear. No, there was a rational, reasonable way to resolve these issues, and my father had faith in people’s ability and in the state

of Israel. He certainly could have done a better job expressing himself at times, and at giving some validation to the fact that the rest of us were afraid and may have needed reassurance as opposed to orders and edicts. But then again, he was a general.

Whenever Dr. Sartawi called our home from Paris, his code name was The Friend. “Hello, is Matti home? This is the friend speaking.” When I heard that, I would be filled with a sense of excitement and importance, and I would rush to get my father. Then I would leave the room immediately.

One discussion they had was about creating a Palestinian state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, what was later named, “The Two-State Solution.” For Yasser Arafat to give up all of Palestine with the exception of the West Bank and Gaza—two pockets of land that amount to 22 percent of Palestine—was an enormous concession to make before official negotiations began. The official line of Fatah—a main Palestinian liberation party and a major faction of the PLO—was to support one secular democratic state that would include Arabs and Jews and allow the return of the Palestinian refugees. Arafat had serious people around him who saw the two-state solution as an option that was both pragmatic and practical. Others within Fatah vehemently disagreed, claiming they could not abandon the millions of refugees who wanted to return to their homes and land in what was now Israel. Arafat had to tread carefully between these two camps. He wouldn’t officially endorse a two-state solution until 1988, but the idea was born in these early years when he let his advisors speak with prominent Zionists.

Upon his return from these trips, my father would meet with Yitzhak Rabin, then in his first term as prime minister. He wanted to brief Rabin on his talks with the Palestinians and to convince him that the time was right for the Israeli government to engage in official talks with the PLO. Everyone thought highly of Rabin as a person and of his abilities as an officer and a leader. When I would hear my father start a sentence with “Yitzhak said,” I knew it was important. But it was never blind admiration; there were many times where my father forcefully criticized Rabin.

I remember one occasion when Rabin came to our house to be briefed. He had visited our house before for social gatherings, weddings, and other family celebrations, and our families knew each other well as a result of the many years the two men worked together while in uniform. Even in the early days it was always a big deal when Rabin came to visit because he was the subject of great admiration. “Will Yitzhak be there? Will he be coming?” people would ask my mother. “Yes, Yitzhak will be coming.”

Now when the prime minister visits your house, it is a big deal. A team of secret service agents positioned themselves at each of the many entryways to our house. Military jeeps positioned themselves at the main intersections leading to our home and a helicopter hovered overhead. And then the prime minister’s motorcade appeared, and we went out to greet him.

The two men sat in our spacious living room, and my father asked that they have the room to themselves. I was 12 or 13 at the time, so I went outside and talked with the secret service guys.

I grew up believing that peace, even if difficult, was sure to come. That belief was bolstered in November 1977, when it was announced that Egyptian President Anwar Sadat would visit Jerusalem. And he would do it with no guarantee that his gesture would bring any tangible results.

It was unthinkable, unbelievable—an unprecedented and truly courageous act of good faith. An entire nation sat glued to their televisions as the Egyptian presidential plane landed in Tel Aviv. Many people simply did not believe it would happen until they saw the impressive figure of President Sadat step out of the plane.

The Israeli honor guard played a marching tune as he strode down the stairs and ceremoniously inspected the troops. Highway 1, the main highway that leads from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem was closed for the occasion. We lived only minutes from the highway, so I ran with dozens of friends to see the motorcade and wave signs in Arabic that said,

Ahlan wa Sahlan Rais El Sadat!

Welcome President Sadat!

Sadat was welcomed at the entrance to Jerusalem with traditional bread and salt by the chief rabbis. He went to pray at the Al Aqsa Mosque in the Old City of Jerusalem, and then he spoke at the Knesset in Arabic in front of a full house and a packed visitors’ gallery. It was a day of profound, almost delirious jubilation. Peace with an Arab nation was at hand.

I was in high school at the time and my father was on sabbatical at Harvard. He had good relations with the Egyptian ambassador to the United States, and this, along with the goodwill that came about as a result of Sadat’s visit, resulted in an invitation for him and my mother to visit Egypt. Theirs must have been the very first Israeli passports stamped with Egyptian visas.