Read The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine Online

Authors: Miko Peled

Tags: #BIO010000

The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine (12 page)

In late 1994, a few months after my first son Eitan was born in San Diego, a sharp pain in my father’s lower back presaged the diagnosis of incurable pancreatic cancer. We had known about the pain for some time, and we hoped it was an orthopedic issue that could be fixed. But then we got the call that it was cancer.

Despite pain and rapid deterioration of his health, my father remained active until his last days, dedicating himself to his research of Arabic literature, to advancing a dialogue of mutual respect between Israelis and Palestinians, to mitigating the plight of soldiers jailed for refusing to serve in the occupied territories, and to his political writings.

His final academic work was the translation, from Arabic to Hebrew, of a book called

The Sages of Darkness

by the Syrian-Kurdish writer Salim Barakat. It was a big project, and he had many exchanges with the writer, which he greatly enjoyed. He used a modem to communicate with Barakat over the Internet. For this last work of his, he was awarded the Israeli Translators’ Association Award. He gave me an inscribed copy, which of course I cherish.

My father’s last political article was titled “A Requiem to Oslo” and appeared in a magazine published by The Israel Council for Israeli-Palestinian Peace.

11

There

he predicted the disastrous end to the peace process. He argued that the process had already reached an impasse from which it may not recover. “The failure was due, quite clearly,” he wrote, “to Rabin’s refusal to redeploy forces on the West Bank and allow general elections to be held in the Occupied Territories.” He continued:

When my my father was making a point, he was often compared to one of the prophets who chastised the people of Israel.

The real cause for Israel’s position is that the results of general elections confirming Arafat as the unchallenged leader of the Palestinian people, would place the Palestinian side closest that they ever came to statehood status.

This he said during the years that Rabin was receiving the Nobel Peace Prize and the world saw him as

the

man of peace. So, once again, he was saying the unthinkable.

When we learned of my father’s illness, Gila and I decided not to wait to take Eitan to see his grandfather. We ended making two trips to see my father, going once in October of 1994 and then again in December.

It was very moving to see Father so frail yet still sharp and smiling. We took several pictures of him as he held Eitan. We also had a wonderful family gathering with all four siblings, Yoav, Nurit, Ossi, and I with our spouses and children. My father told stories, and we all listened intently, suspecting that this might

be our last gathering where he was still well enough to speak. Now I wish I had recorded the moment, because try as I may I can’t recall what stories he told us that evening. Over the days and weeks that I was with him, I kept asking my father to write about himself and about his life, but he refused. “I find it boring to write about myself,” he insisted, and he wouldn’t consent for me to record him either. He was very optimistic about his recovery and his mood for the most part was quite relaxed.

Smadari was there too. Naomi Shemer, Israel’s most beloved songwriter and an old friend of the family, wrote a poem in his honor. The poem begins with the words, “The body’s betrayal, the loyalty of spirit,” alluding to Father’s sharpness of mind even as his body was being eaten by the cancer.

I continued to visit every few months on my own. As his condition got worse there was no point in Gila and Eitan coming along. The third time I visited, my father had just begun receiving chemotherapy, and I went straight from the airport to the hospital. “How are you?” I asked. He looked terrible.

“Miserable,” he replied, and then added, “You should go home and rest, you must be exhausted from the long flight.” He was never an easy man, but he was a little more relaxed as a grandfather than he was as a father. The disease accentuated his moods so when he felt good he was actually quite jovial, but when the pain hit him or the chemo was in him, he was miserable.

I stayed about 10 days. My mother decided to care for him at home as opposed to a hospice. On my fourth visit I stayed till the end. He held on to life as long as he could, believing until the very end that medicine would cure him. Finally, in the early morning hours of March 10, 1995, he succumbed to the disease. My mother and siblings had been taking shifts staying by his bedside. I was with him at 4 a.m. when he took his final breath. He died in his bed in the home he loved so dearly.

We decided against burying Father at the military cemetery on Mount Herzl in Jerusalem. His legacy was so much more than his military service, and if he’d been buried in the military cemetery, his tomb would have said simply that he was a general and when he was born and when he died. However, more than half his life was about other things—Arabic literature, activism, and peace. So my mother purchased a plot on a hillside cemetery in Kibbutz Nachshon, just outside Jerusalem. We felt it more appropriate to lay him to rest in a beautiful forest near his home in Jerusalem, where we could put what we wanted on his tombstone.

The funeral was a full military ceremony. When the Jeep showed up at our house with the coffin—on its way to the cemetery—we stepped out to see it and say goodbye. Six generals would carry my father’s coffin, and they sat around the coffin chatting. As we walked up to the Jeep, they hurriedly hushed one another to look dignified. My mother rested her head on the coffin and cried.

My father’s generation, the bright, young officers who won the war of 1948 for us and then went on to become the generals of the 1967 war, were

iconic, and my father’s role in the buildup to the Six-Day War reached almost mythical proportions. That alone would have made the funeral a major event. It also brought together an unprecedented combination of Israeli generals, heads of state, and radical peace activists as well as Palestinian leaders. Messages of condolence were read from both the government of Israel and Yasser Arafat. Dr. Ahmed Tibi came to represent Arafat (as Arafat himself was not permitted to enter Jerusalem) and lay a wreath on the grave on his behalf. It was placed next to the wreath from the President of Israel. As I recall this, I still find it hard to believe: The first Palestinian president presenting a wreath and a message of condolence on the grave of an Israeli general. The press noticed this, and the photo of the two wreaths side by side made its way into many newspapers.

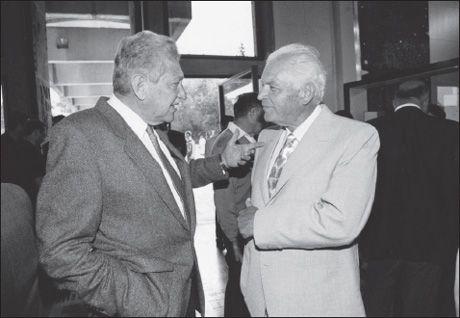

Eyzer Weizman, former commander of the Israeli Air Force and Deputy Chief of Staff. He was one of my father’s few life long friends. Here he is in his last formal post, President of the state of Israel.

From Uri Avnery on the left to Ariel Sharon on the right, everyone came to pay respects. The army chief rabbi who ran the ceremony asked me to say the

kaddish

, or “prayer of the bereaved,” and he added, “It’s for father.” I did say the mourners’

kaddish

, but I couldn’t help thinking that if he knew anything about my father, he would know not to say such nonsense. Father had no tolerance for religion or religious ceremonies.

My father’s death prompted countless news stories in Israel and around the world, many of which attempted to analyze his career and his personality. I found

two pieces, one by a Palestinian and indeed world-renowned professor Walid Khalidi

12

and the other by Israeli veteran journalist and lifelong peace activist Uri Avnery

13

, particularly effective. My father’s close ties with these two men and the kind words they wrote upon his passing demonstrate the quantum leap he had taken over the years since his military service ended. Dr. Khalidi wrote among other things, “Matti was no diplomat. Well ahead of his time and against daunting opposition, he had cut through the century-old Arab-Zionist conflict and had developed deep convictions with regard to its resolution.”

Avnery summed up his written eulogy with the words, from Shakespeare’s Hamlet, “He was a man, take him for all in all—I shall not look upon his like again.”

It’s true that Matti Peled could be difficult, but he was greatly respected and admired. He distinguished himself with his commitment first as a military expert and then as a peace activist and advocate. True, he did not allow for much discussion, but his lectures at the dinner table were always illuminating, and I received much of the confidence I have in my identity as a Jewish Israeli from him.

Yitzhak Rabin, then prime minister, also attended my father’s funeral, as protocol called for it. But he never called to say farewell to my dying father as all his other comrades in arms did, nor did he visit our home during the

Shiv’a

, the traditional seven days of mourning, to express his condolences. Tragically, eight months later, Rabin too was dead—murdered by a Jewish boy who was raised on the toxic mix of Orthodox Judaism and radical Zionism. It was the end of an era and the beginning of great uncertainty.

1

Matti Peled, “The beauty has not faded,”

Ma’ariv

, June 15, 1973.

2

The 1973 Mideast War, also called The Yom Kippur War, began on the Jewish Holiday of Yom Kippur, October 6, 1973. Egyptian and Syrian forces attacked Israel and caught the IDF by surprise, which resulted in panic and many casualties. A special inquiry, the Agranat Commission was set up to investigate the IDF failings. It found IDF top brass responsible and several generals, including the IDF chief of staff, had to resign. Prime Minister Golda Meir, who remained unscathed by the commission, had to resign as well as a result of popular protests.

3

Matti Peled, “The Palestinian Problem,”

Ma’ariv

, June 27, 1969.

4

Matti Peled, “Thoughts at Beginning of the Fourth Year,”

Ma’ariv

, June 5, 1970.

5

Matti Peled, “Who Heard of the Palestinians?”

Ma’ariv

, March 23, 1973.

6

Fedayeen are people who volunteer to fight for a cause. They were Palestinian freedom fighters, but to us the name meant terrorists.

7

Henri Curiel, an Egyptian-Jewish communist, living in exile in Paris, played a key role in facilitating the opening of these contacts. He was assassinated in 1978. It remains a mystery who killed him.

8

Matti Peled, “My meetings with PLO representatives,”

Ma’ariv

, July 1, 1977.

9

Palestinian-Israelis are Palestinians who live within Israel and have Israeli citizenship. Israelis usually refer to them as “Arab-Israelis” Around 1.5 million Palestinians live in Israel as Israeli citizens.

10

Sima Kadmon, “Rabin Does Not Want Peace,”

Ma’ariv

, August 16, 1993.