The Glimmer Palace (19 page)

Read The Glimmer Palace Online

Authors: Beatrice Colin

Tags: #Fiction, #Literary, #Historical, #War & Military

The three Germans were imprisoned for several weeks. And then a halt was called to firing and they were brought to the front line and pushed over the brink of a French trench.Tentatively they made their way across what would soon be known as no-man’s-land, with their polished boots and their shining buttons, the unsounded bugle and the rolled-up white flag, splattered and soiled by the freshly churned-up mud.

Lilly saw Otto once more that year, on a temporary ice rink in an empty lot in late 1914. He was wearing a uniform and holding the hands of a girl with red hair and a purple muffler. As Lilly watched, Otto turned and started pulling the girl round and round the rink. And the more the girl screamed and told him to stop, the faster he skated. And then, digging the blades of his skates into the ice, he came to a skidding stop and the girl, with skates parallel and cheeks aflush, flew straight into his open arms.

He was dead by Christmas. His boots were stolen from his body by a boy from Silesia who deserted and walked all the way home, only to be shot by his own father.

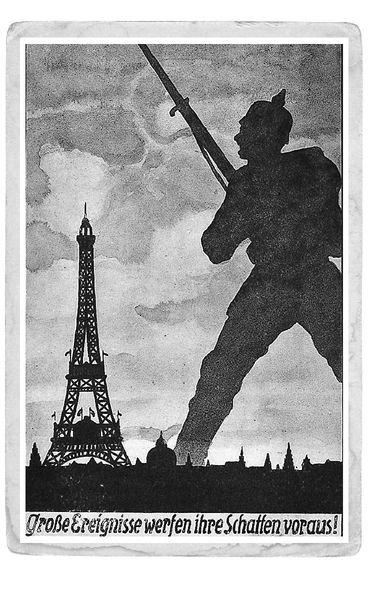

Thunder Clouds

K

reuzberg. The Palace Movie Theater. November 1914. The frontiers are closed. All foreign films are banned. No more Westerns, no more Charlie Chaplin or Tontolini. Just German films. The newsreel has started when Greta and her mother take their seats. On screen, the soldier holding the gun somewhere in France is young and blond. He bangs the door of a whitewashed barn with his fist. Five French soldiers come out of the barn with their hands upon their heads.

And yet, and yet, the third French soldier looks familiar. “It’s Philip,” Greta whispers. “Don’t you see?” Despite the uniform and the hands across the face, it’s him, her brother. “Why would he agree to do such a thing?”

Why did he walk down that lane in France, ten miles at least from the entrenchment known as the Front. Why? Because there was no mud, no blood, no gangrene or other bodily fluids, no death, no pain, no fear. Just uniforms taken from French corpses buttoned over stomachs still digesting the extra bratwurst each of them received in payment.

Greta’s tear-filled eyes hold on to the roll of her brother’s shoulder, the stamp of his feet in polished boots, the back of his head clasped with those still-familiar hands, while the people in the audience almost cheer the roof off.

“We’re winning the war,” they shout. “Our boys’ll be home before you know it.”

Greta and her mother both leave before the feature.

Years later, Lidi’s abrupt and unexpected exits were legendary. It was said that she could be halfway through a film or a dinner or a conversation, with a glass in one hand and a fork in the other, when she would suddenly hand them over to the nearest person and make for the door. And she would quite often leave without her coat.

But in the early days of the Great War, after being sacked for alleged infidelities with her employer’s husband, Lidi’s exit was anything but glamorous. She packed her cardboard suitcase, folded the maid’s uniform, placed it back in the bottom drawer where she had found it, and put on the Countess’s daughter’s blue dress. And then she left all the books that the penniless poet had given her, except one, on the bedside table, opened the window with its view of a wall, and pulled the door to for the final time.

Lilly, as she was known then, walked away from the villa where she had worked for so many months and did not look back. If she had, she might have noticed that from the outside the house seemed so still, so rigid that it was almost as if it had been sent to sleep forever. It did, in fact, stand virtually unchanged until 1945, when it was blown to bits by Russian shells.

It was a hot, windless late-August day. In gardens full of blossom, women in pale dresses poured lemonade from tall glass jugs.The soft clink of croquet balls and the occasional whoop of drunken young men drifted from the far reaches of smooth grass lawns. An open-topped omnibus motored past, the top deck full of couples with picnic baskets and straw hats. A horse and cart from the country clopped along behind it, laden with baskets of strawberries. A distant church bell struck two.

The doctor noticed the maid as he passed in a horse-drawn cab, but he did not stop. Earlier that day, he had spotted the kaiser’s motorcar racing through the streets to another meeting at the Reichstag. The German army had defeated the French on the Western Front. The whole city was full of flags. Dr. Storck’s excitement was such that he, too, would also enlist only a few months later. His role as a physician to a small group of wealthy ladies, however, did nothing to prepare him for the field hospital in Poland on the Eastern Front where he was posted in January 1915. Faced with small wounds oozing with gangrene that would rapidly kill otherwise healthy men, daily amputations, and a never-ending stream of horrific and usually fatal injuries, the doctor sometimes sat down, wept copiously, and had to be coaxed back to work by one of the nurses with hot tea laced with Polish vodka.

On that hot summer day, however, when the whole country seemed to be on holiday as people sauntered and strolled and even promenaded, Lilly walked at a pace that suggested she was going somewhere, that she was even a little late. As she walked she tried to clear her head, she tried to work out what she would do and where she would go. First she would have to find a room in a boardinghouse. But that wouldn’t be easy: the rental barracks, as they were known, were overcrowded with workers from eastern Prussia. And then she would have to find another job. She was old enough to find work in a factory. Now that so many men had enlisted, it was rumored that they had started to employ more women. But why even do that? I am free, she told herself. I can go anywhere, do anything, and be anyone. I have no past, only a future.

And then the idea occurred to her that she ought to try to find some of her relatives. And yet they had never tried to seek her out. They must have known she existed. They must have seen the newspaper article.The road surface changed beneath her feet from cobbles to twin tracks of dust. The houses were built farther apart here, and saplings had been planted in long lines along what would be the curb. The smell of rye drifted in from the fields where migrant Russians and Poles were bringing in the harvest. Lilly realized that she had been inadvertently walking away from the city instead of toward it.

On a corner was a signpost. She was heading in the direction of Potsdam. On the horizon, anvils of gray cloud were looming up and rolling closer.The air was filled with electricity.The sun was too hot. Her shoes were too small. The suitcase was too heavy. And so there, just level with the signpost, as a pair of magpies flitted from fence to hedgerow and back again, she stopped. An image of Marek in the summerhouse came into her mind before she could prevent it. He had fooled her; she was indeed worthless, disposable. There was grit in her eyes, her mouth, her throat. No wonder she didn’t hear the car approaching.

The Daimler convertible slammed on its brakes, its tires bit into the dust, but it did not stop in time. Lilly didn’t even raise her arms as a wall of polished chrome and painted metal came skidding toward her. It hit her so hard that she flew up into the air and over the hood before coming to land, hard, on the rough surface of the soon-to-be suburban road.

When she opened her eyes, she was momentarily surprised that she was still alive. And then she noticed that she had lost her shoes. Her dress was torn and both stockings were shredded at the knee. The contents of her suitcase were strewn along the road. A drop of blood fell from her temple and landed on her hand. She sat up. Nothing seemed to be broken.

“My dear girl,” a woman’s voice said. “I didn’t see you.”

“You should have been looking where you were going, Eva,” a man’s voice scolded. “She could have been killed. Are you all right?”

A couple had climbed out of the car. Both were wearing driving goggles.

“Can you walk?” the woman asked Lilly.

“Of course she can’t walk,” the man interrupted.

He turned to her and held out his hand.

“I knew I should never have let my sister drive a car. I’m so sorry. Are you hurt?”

“I don’t think so,” Lilly replied.

But they didn’t seem to be listening. Still arguing, they placed their hands under her arms and gently hoisted her up.The heat of the road burned her feet through her thin cotton stockings. Her head was spinning.

“I think I need to . . .” Lilly said.

“Sit down,” the woman ordered.

Lilly sank onto the wide wooden running board of the car. Here, at least, there was some shade. And then the woman noticed Lilly’s dress.

“Oh, you’re at Luisenstadt.” The woman pulled off her goggles, leaving two dark red rings around her eyes.

The Countess had given her maid the unworn uniform of the expensive private school that she had wanted her daughter to attend. The blue serge was dirty and the hem was torn but the style was unmistakable.

“Let me get your suitcase? . . .” She paused at the end of the sentence, as if expecting something else of her. The woman was only a little older than Lilly, with fair hair, a strong chin, wide cheeks, and small flint-blue eyes. She wore a gray linen dress with a hobbled skirt. She inclined her head. Finally Lilly understood: she wanted to know her name.

“Thank you,” she said. “It’s Lilly.”

“Lilly. It’s the least I can do,” she replied.

While she ran back and forth collecting camisoles and other undergarments, dresses and stockings, her brother brought out a hip flask from the car and offered her some apple schnapps. Lilly hesitated. He pulled off his goggles and leather cap.

“Have some,” he said. “Go on. It’s nice and cold.”

He was wearing tall boots, breeches, and a flannel coat. He had the same wide face as his sister but his features were in almost the opposite configuration. His nose was narrow and freckled with sun. His eyes were wide and startlingly blue. He was as handsome as she was plain.

Looking back, Lilly wondered why they had not interrogated her further.They did not seem remotely curious about what she had been doing in the middle, it could be fairly judged, of nowhere with a suitcase. Lilly took a small sip and the schnapps burned her throat and made her cough. And so she took another and felt better. And then, from the corner of her eye, she saw the newspaper cutting about her parents on the ground a few feet away. As she watched, a motorcar veered past, heading toward the city. Caught in the tailwind, the snippet of newspaper blew over a hedge and was gone. Let it go, she told herself, it doesn’t matter. And she wiped the dust and the tears from her eyes. In response, the man clumsily sat down beside her and put his arm around her shoulder. He smelled of leather, French cologne, and alcohol.

“Don’t worry,” the man whispered. “It’s the shock. My horse threw me last year, and apart from the bruises, I felt quite odd. I was filled with sadness when there was nothing to be sad about. Lasted about a week.”

He glanced round at her as if he was suddenly aware that he’d given her too much information too soon.

“Anyway, we should be on the safe side. Let’s drive back into town and call our doctor.”

“No,” Lilly replied. “Really, I’m fine.”

“You’re not fine,” he replied. “And then, after you’ve seen the doctor, we’ll drive you home. Apart from anything else, you’re not wearing any shoes.”

Lilly opened her mouth to protest. But it was true. She wouldn’t get very far without shoes. And so they sat in silence for a few moments, the apple schnapps making its way straight into her bloodstream.

“Aren’t you . . . ?” she asked.

“Going somewhere?” he asked. “If you call lost going somewhere. My sister can’t read a map.That’s why she was driving.We were going to see the fountains of Sanssouci before they switch them off for the season. Have you been yet?”

Lilly shook her head.

“Don’t blame you. It was my sister’s idea,” he went on. “Anyway, we need to get back to the city. You know how it is, people to see, things to do.”

The sunlight was as clear as a lens. He pointed out a bird, a lark that had settled on a wooden fence and started to sing.They watched it until it flew away, and then she turned and noticed that he had not been looking at the lark at all.

Just then, the sister came back with her arms full of Lilly’s belongings.

“We have this too,” the girl said, holding up the book of poetry. She hadn’t found the shoes. Or the box with the photographer’s lens and the postcard of the Virgin Mary.

Lilly rode in the backseat of the Daimler with a thick woolen rug tucked around her despite the heat and her suitcase strapped on to the luggage rack on the rear.The man had taken the wheel and the car roared as he turned a corner too fast and shook as it sped over tram-lines. Although his sister regularly turned and spoke, the noise of the engine was so loud that it was impossible to hear a word. Lilly sat back and tried to take it all in; it was the first time she had ever traveled in a car.

At the Unter den Linden there was a huge traffic jam. Crowds of people had crammed into the streets to watch the new army recruits parade past in their brand-new uniforms and spiked helmets. The men were heading to the railway station at Zoo, where trains were waiting to ship them to the front.