The Grand Alliance (30 page)

Read The Grand Alliance Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II

Hitherto help from across the ocean had been confined to supplies; but now in this growing tension the President, acting with all the powers accorded to him as Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces and enshrined in the American Constitution, began to give us armed aid. He resolved not to allow the German U-boat and raider war to come near the American coast, and to make sure that the munitions he was sending Britain at least got nearly halfway across. As early as July, 1940, he had sent a naval and military mission to England for “exploratory conversations.” Admiral Ghormley, the United States Naval Observer, was soon satisfied that Britain was inflexibly resolved, and could hold out against any immediate threat. His task, in collaboration with the Admiralty, was to determine how the power of the United States could best be brought to bear, first under the existing policy of “all aid short of war,” and secondly in The Grand Alliance

184

conjunction with the British armed forces if and when the United States should be drawn into war.

From these early beginnings sprang the broad design for the joint defence of the Atlantic Ocean by the two English-speaking Powers. In January, 1941, secret Staff discussions began in Washington covering the whole scene, and framing a combined world strategy. The United States war chiefs agreed that should the war spread to America and to the Pacific the Atlantic and European theatre should be regarded as decisive. Hitler must be defeated first, and on this conception American aid in the Battle of the Atlantic was planned. Preparations were started to meet the needs of joint ocean convoy in the Atlantic. In March, 1941, American officers visited Great Britain to select bases for their naval escorts and air forces.

Work on these was at once begun. Meanwhile the development of American bases in British territory in the West Atlantic, which had begun in 1940, was proceeding rapidly. The most important for the North Atlantic convoys was Argentia, in Newfoundland. With this and with harbours in the United Kingdom American forces could play their fullest permissible part in the battle, or so it seemed when these measures were planned.

Between Canada and Great Britain are the islands of Newfoundland, Greenland, and Iceland. All these lie near the flank of the shortest, or great-circle, track between Halifax and Scotland. Forces based on these “stepping-stones” could control the whole route by sectors. Greenland was entirely devoid of resources, but the other two islands could be quickly turned to good account. It has been said,

“Whoever possesses Iceland holds a pistol firmly pointed at England, America, and Canada.” It was upon this thought that, with the concurrence of its people, we had occupied Iceland when Denmark was overrun in 1940. Now we could The Grand Alliance

185

use it against the U-boats, and in April, 1941, we established bases there for the use of our escort groups and aircraft. Iceland became a separate command, and thence we extended the range of the surface escorts to 35°

West. Even so there remained an ominous gap to the westward which for the time being could not be bridged. In May a Halifax convoy was heavily attacked in 41° West and lost nine ships before our anti-U-boat escort could join it.

Meanwhile the strength of the Royal Canadian Navy was increasing, and their new corvettes were beginning to emerge in good numbers from the building yards. At this crucial moment Canada was ready to play a conspicuous part in the deadly struggle. The losses in the Halifax convoy made it quite clear that nothing less than end-to-end escort from Canada to Britain would suffice, and on May 23 the Admiralty invited the Governments of Canada and Newfoundland to use St. John’s, Newfoundland, as an advanced base for our joint escort forces. The response was immediate, and by the end of the month continuous escort over the whole route was at last a reality. Thereafter the Royal Canadian Navy accepted responsibility for the protection, out of its own resources, of convoys on the western section of the ocean route. From Great Britain and from Iceland we were able to give protection over the remainder of the passage. Even so the strength available remained perilously small for the task to be performed.

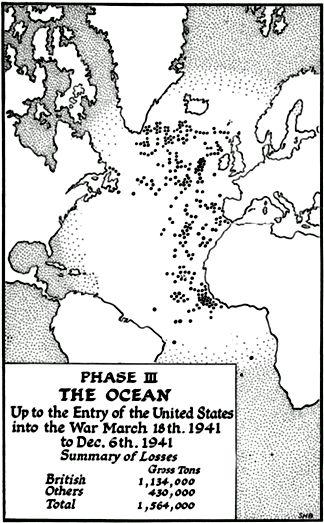

Meanwhile our losses had been mounting steeply. In the three months ending with May U-boats alone sank 142

ships, of 818,000 tons. Of these, 99 ships, of about 600,000

tons, were British. To achieve these results the Germans maintained continuously about a dozen U-boats in the North Atlantic, and in addition endeavoured to spread-eagle

The Grand Alliance

186

our defence by determined attacks in the Freetown area, where six U-boats in May alone sank thirty-two ships.

In the United States the President was moving step by step ever more closely with us, and his powerful intervention soon became decisive. As we had found it necessary to develop bases in Iceland, so he in the same month took steps to establish an air base for his own use in Greenland.

It was known that the Germans had already installed weather-reporting stations on the Greenland east coast and opposite Iceland. The President’s action was therefore timely. Furthermore, by other decisions not only our merchant ships but our warships, damaged in the heavy fighting in the Mediterranean and elsewhere, could be repaired in American shipyards, thus giving instant and much-needed relief to our heavily strained resources at home. The President confirmed this in a telegram of April 4, which also stated that he had allotted funds to build another fifty-eight launching yards and two hundred more ships.

Former Naval Person

4 April 41

to President Roosevelt

I am most grateful for your message just received

through the Ambassador about the shipping.

2. During the last few weeks we have been able to

strengthen our escorts in home northwestern approaches, and in consequence have hit the U-boats hard.

They have now moved farther west, and this morning

(April 3) sank four ships on the twenty-ninth meridian

one day before our escort could meet them. Beating the

U-boat is simply a question of destroyers and escorts,

but we are so strained that to fill one gap is to open

another. If we could get your ten cutters taken over and

manned we would base them on Iceland, where their

good radius would give protection to convoys right up to

The Grand Alliance

187

where they meet our British-based escorts. Another

important factor in northwestern approaches is long-distance aircraft. These are now coming in. Meanwhile,

though our losses are increasingly serious, I hope we

shall lessen the air menace when in a month or six

weeks’ time we have a good number of Hurricane

fighters flying off merchant ships patrolling or escorting

in the danger zone.

Great news arrived a week later. The President cabled me on April 11 that the United States Government proposed to extend their so-called security zone and patrol areas, which had been in effect since very early in the war, to a line covering all North Atlantic waters west of about West Longitude 26°. For this purpose the President proposed to use aircraft and naval vessels working from Greenland, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, the United States, Bermuda, and the West Indies, with possibly a later extension to Brazil. He invited us to notify him in great secrecy of the movement of our convoys, “so that our patrol units can seek out any ships or planes of aggressor nations operating west of the new line of the security zones.” The Americans for their part would immediately publish the position of possible aggressor ships or planes when located in the American patrol area. “It is not certain,” the President ended, “that I would make a specific announcement. I may decide to issue the necessary naval operative orders and let time bring out the existence of the new patrol area.”

The Grand Alliance

188

The Grand Alliance

189

I transmitted this telegram to the Admiralty with a deep sense of relief.

Former

Naval

16 April 41

Person to President

Roosevelt

I had intended to cable you more fully on your

momentous message about the Atlantic. Admiralty

received the news with the greatest relief and satisfaction, and have prepared a technical paper. They

wonder whether, since Admiral Ghormley arrives here

in about two days, it would be better to discuss this with

him before dispatch. I do not know whether he is

apprised or not. The matter is certainly of highest

urgency and consequence. There are about fifteen U-boats now operating on the thirtieth meridian, and of

course United States flying-boats working from Greenland would be a most useful immediate measure.

Two days later, on April 18, the United States Government announced the line of demarcation between the Eastern and Western Hemispheres to which the President had referred in his message of April 11. This line, drawn along the meridian of 26° West, became thereafter the virtual sea frontier of the United States. It included within the United States’ sphere all British territory in or near the American continent, Greenland, and the Azores, and was soon afterward extended eastward to include Iceland. Under this declaration United States warships would patrol the waters of the Western Hemisphere, and would incidentally keep us informed of any enemy activities therein. The United States, however, remained non-belligerent and could not at this stage provide direct protection for our con¬voys. This remained solely a British responsibility over the whole route.

Both the British and American naval chiefs were at this time anxious about the Azores. We strongly suspected that the The Grand Alliance

190

enemy were planning to seize them as a base for U-boats and aircraft. These islands, lying near the centre of the North Atlantic, would in enemy hands have proved as great a menace to our shipping movements in the south as Iceland in the north. The British Government for its part could not tolerate such a situation arising, and in response to urgent calls from the Portuguese Government, who were fully alive to the danger to their own country, we planned and prepared an expedition to forestall such a German move. We had also made plans to occupy Grand Canary and the Cape Verde Islands, should Hitler move into Spain.

The urgency of these expeditions vanished once it became clear that Hitler had shifted his eyes towards Russia.

Former

Naval

24 April 41

Person to President

Roosevelt

I now reply in detail to your message of April 11. The

delay has been caused by waiting for Admiral Ghormley, whose arrival was uncertain. The First Sea Lord

has had long discussions with Ghormley, as the result

of which I am advised as follows:

2. In the Battle of the Atlantic we have two main

problems to deal with in addition to the menace from

aircraft round our coast. These problems are those of

the U-boats and the raiders.

3. As regards the U-boats, we have had considerable success in dealing with these pests when they

were working somewhere in the longitude of 22° West

in the northwestern approaches. Whether it was because of our success or for some other reason, they

are now working in about 30° West.

4. We have, however, been able gradually to

strengthen our escorting forces, thanks to the United

States destroyers which were sent us, and by the use

of Iceland as a refuelling base for the escorts.

5. It may be expected that the enemy’s reaction to

this will be to send his U-boats still farther west, and as

The Grand Alliance