The Grand Alliance (26 page)

Read The Grand Alliance Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II

He is very glad to see that there is a sharp recovery

in the last two weeks, and he hopes this may be the

first fruits of the Import Executive.

The Prime Minister will be glad to see the Import

Executive Committee at 5 P.M. on Tuesday, with a view

to learning from them whether they have any further

measures to propose to avert a potentially mortal

danger.

The Grand Alliance

161

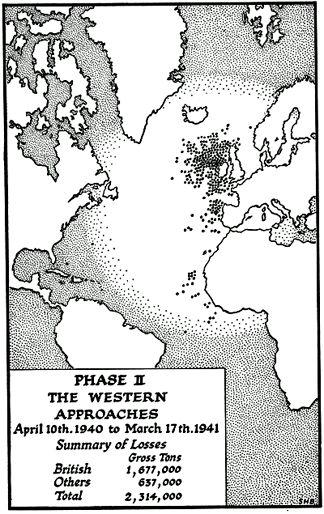

As early as August 4, 1940, I had asked the Admiralty to move the controlling centre of the western approaches from Plymouth to the Clyde.

2

This proposal had encountered resistance, and it was not until February, 1941, that the increasing pressure of events produced Admiralty compliance. The move to the north was agreed. The Mersey was rightly chosen instead of the Clyde, and on February 17 Admiral Noble was installed at Liverpool as Commander-in-Chief of the western approaches. Air Chief Marshal Bowhill, commanding the Coastal Command, worked with him in the closest intimacy. The new joint headquarters was soon operating, and from April 15 the two commands were forged into a single highly tempered weapon under the operational control of the Admiralty.

The new year opened with violent and almost continuous storms, causing much havoc among the older ships which, despite their age and infirmity, we had been compelled to use on the ocean routes. Presently, in Berlin, on January 30, 1941, Hitler made a speech threatening us with ruin and pointing with confidence to that combination of air and sea power lapping us about on all sides by which he hoped to bring about our starvation and surrender. “In the spring,” he said, “our U-boat war will begin at sea, and they will notice that we have not been sleeping [shouts and cheers]. And the air force will play its part, and the entire armed forces will force a decision by hook or by crook.”

The Grand Alliance

162

The Grand Alliance

163

Prime

Minister

to

25 Feb. 41

Import Executive

I learn that the Admiralty salvage organisation has

recently made as great a contribution to the maintenance of our shipping capacity as new construction,

about 370,000 gross tons having been salved in the

last five months of 1940, as against 340,000 tons built,

while the number of ships being dealt with by the

salvage organisation has increased very rapidly, from

ten in August to about thirty now.

They are to be congratulated on this, and I feel sure

that if anything can be done to assist in the expansion

of their equipment and finding of suitable officers your

Executive will see that such measures are taken.

Meanwhile we cannot take full advantage of these

results owing to shortage of repairing capacity. I have

no doubt that your Executive is planning an increase of

this capacity, and meanwhile is making use of facilities

overseas in the case of all vessels capable of doing

one more voyage before repair.

Apart from the U-boat war upon us, we were at this time seriously affected by the sorties of powerful German cruisers. The attack on a convoy by the

Scheer

in November, 1940, when she sank the noble

Jervis Bay,

has already been recorded. In January she was in the South Atlantic, moving towards the Indian Ocean. In three months she destroyed ten ships, of sixty thousand tons in all, and then succeeded in making her way back to Germany, where she arrived on April 1, 1941. We had not been able to deploy against her the powerful forces which a year before had tracked down the

Graf Spee.

The cruiser

Hipper,

which had broken into the Atlantic at the beginning of December, 1940, was sheltering in Brest. At the end of The Grand Alliance

164

January the battle-cruisers

Scharnhorst

and

Gneisenau,

having at length repaired the damage inflicted upon them in Norway, were ordered to make a sortie into the North Atlantic, while the

Hipper

raided the route from Sierra Leone. In their first attempt to break out, these battle-cruisers, under the command of Admiral Lutjens, narrowly escaped destruction by the Home Fleet. They were saved by persistent fogs, and on February 3 successfully passed through the Denmark Strait unobserved. At the same time the

Hipper

had left Brest for the southward.

On February 8 the two German battle-cruisers, astride the Halifax route, sighted an approaching British convoy. The German ships separated so as to attack from different angles. Suddenly, to their surprise, they perceived that the convoy was escorted by the battleship

Ramillies.

Admiral Lutjens at once broke off the engagement. In his basic instructions he had been ordered to avoid action with an equal opponent, which he was to interpret as meaning any one British fifteen-inch-gun battleship. His prudence was rewarded, and on February 22, he sank five ships, dispersed from an outward-bound convoy. Fearing our reactions, he then moved to an area farther south, and on March 8 he met a convoy from Freetown. But here again he found a battleship, the

Malaya,

in company, and he could do no more than call for U-boats to converge and attack.

The U-boats sank five ships. Having shown himself in this area, he once more returned to the West Atlantic, where he now achieved his biggest success. On March 15 he intercepted six empty tankers, dispersed from an outward-bound convoy, and sank or captured them all. The next day he sank ten more ships, mostly from the same convoy.

Thus in these two days alone he destroyed or captured over eighty thousand tons of shipping.

The Grand Alliance

165

But the

Rodney,

escorting a Halifax convoy, was drawing near. Admiral Lutjens had run risks enough and had much to show. Early on March 22 he entered Brest. During their cruise of two months the

Scharnhorst

and

Gneisenau

had sunk or captured twenty-two ships, amounting to 115,000

tons. Meanwhile the

Hipper

had fallen upon a homeward-bound Sierra Leone convoy near the Azores which had not yet been joined by an escort. In a savage attack lasting an hour she destroyed seven out of nineteen ships, making no attempt to rescue survivors, and regained Brest two days later. These were heavy losses for us, additional to the toll of the U-boat war. Moreover, the presence of these strong hostile vessels compelled the employment on convoy duty of nearly every available British capital ship. At one period the Commander-in-Chief of the Home Fleet had only one battleship in hand.

The

Bismarck

was not yet on the active list. The German Admiralty should have waited for her completion and for that of her consort, the

Tirpitz.

In no way could Hitler have used his two giant battleships more effectively than by keeping them both in full readiness in the Baltic and allow rumours of an impending sortie to leak out from time to time. We should thus have been compelled to keep concentrated at Scapa Flow or thereabouts practically every new ship we had, and he would have had all the advantages of a selected moment without the strain of being always ready. As ships have to go for periodic refits, it would have been almost beyond our power to maintain a reasonable margin of superiority. Any serious accident would have destroyed that power.

The Grand Alliance

166

My thought had rested day and night upon this awe-striking problem. At this time my sole and sure hope of victory depended upon our ability to wage a long and indefinite war until overwhelming air superiority was gained and probably other Great Powers were drawn in on our side. But this mortal danger to our life-lines gnawed my bowels. Early in March exceptionally heavy sinkings were reported by Admiral Pound to the War Cabinet. I had already seen the figures, and after our meeting, which was in the Prime Minister’s room at the House of Commons, I said to Pound,

“We have got to lift this business to the highest plane, over everything else. I am going to proclaim ‘the Battle of the Atlantic.’” This, like featuring “the Battle of Britain” nine months earlier, was a signal intended to concentrate all minds and all departments concerned upon the U-boat war.

In order to follow this matter with the closest personal attention, and to give timely directions which would clear away difficulties and obstructions and force action upon the great number of departments and branches involved, I brought into being the Battle of the Atlantic Committee. The meetings of this committee were held weekly, and were attended by all Ministers and high functionaries concerned, both from the fighting services and from the civil side. They usually lasted not less than two and a half hours. The whole field was gone over and everything thrashed out; nothing was held up for want of decision. An illustration of the tempo of the Battle of the Atlantic in 1941 is afforded by the meetings of this committee. It met weekly without fail during the period March 19 to May 8. It then met fortnightly for a spell, and finally much less frequently. The last meeting was on October 22.