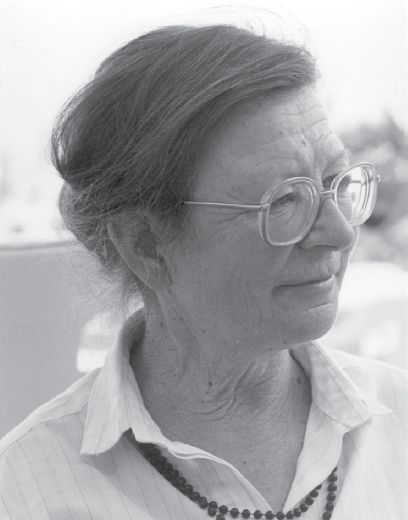

The Heart Has Reasons (15 page)

Then the next day, my friend Hansje van Loghem, one of my sorority sisters, asked me if I’d like to help her and her boyfriend Piet Meerburg to hide Jewish children. I immediately said yes. I didn’t know until then whether I would be brave enough to do something like that. But from that moment on, I never stopped.

Because of my Utrecht connections, I became a liaison between the Amsterdam Student Group, of which Piet was the leader, and the Utrecht Kindercomité run by Jan Meulenbelt. Hetty was in that Utrecht group, and we became fast friends. Then the Nazis said that anyone who had not signed the declaration of loyalty could not attend school, so I moved back in with my family in Utrecht, and Hetty and I worked together every day to help hide Jewish children. My stepfather was employed by the railroad, so I could travel for practically nothing on the trains. That came in handy when transporting the children.

I wasn’t afraid to take the children on the train—I was a little bit stupid, I guess, because I was young. But, come to think of it, no one in my family was really afraid. When I told my mother what I was doing, she said, “Oh! That’s a good idea.” She was a very positive person. Even after my arrest, she always believed that I would be set free and that no harm would come to me. My father was the same way. Our whole family believed that you should go ahead and help, and not worry about it.

How were we arrested? It’s complicated. . . . There was a very nice lady in the east of Holland whose house was big enough to hide about ten Jewish children. They could go outside there, and swim in the river. It was a very good situation for them, and we were trying to come up with more situations like that. And then a certain minister offered us the use of a big house in the south of Holland in a place called Esch, but before bringing children there, we had to find someone to live there who could take care of the children. One of the group members located an older couple that was willing to do it.

We didn’t know them. They moved in very quickly and said, “Very well then, bring us the children.” So we began to bring them children, and we also sent an older Jewish girl over there to provide household help. It was she who overheard them arguing about whether to turn the children in immediately, or wait for more to come. She ran away after that, and hid in Utrecht. At the same time, some Jewish people managed to get a message to us from out of Westerbork—they said that every Jew that couple had been in contact with had been betrayed.

So what must you do at such a moment? If it was only a matter of the children, we could remove them, but they’d met several members of our group, and they knew our contact address. After discussing it for hours, we decided we had to kill them! Imagine us, young college students, having to make such a decision. Rut Matthijsen knew about a knokploeg that did that kind of thing, and we asked them to help us.

The day of the action, Hetty and I bicycled to Esch. The others were already there—Rut was in the woods a little ways from the road, keeping a watch over the four bicycles, while Jan was hiding with the knokploeg near the house. It was a beautiful spring morning, and we went to the front door and told the couple that we wanted to take the children out for a little walk. That was fine, but we saw that their foster son was visiting! What would happen to him? But it was too late to change anything—we strolled down the path with the children, while Jan led the knokploeg to the door. A few moments later we heard gun shots. Hetty looked

back and saw the foster son crawling out the door towards the neighboring farm. We put the three children on our bicycles, and pedaled hard to the train station. Soon we were speeding along the rails to Utrecht, where we safely delivered them to another address.

We learned later that the boys from the knokploeg had only been able to kill the man. The woman was severely wounded with a bullet in her lung, but it was only a matter of time before she had recovered enough to talk. They shot the foster son in the leg because they didn’t know if he was part of it or not, but he knew enough to send the SD after us.

They caught Hetty the next day, and she somehow was able to telephone in order to warn us of the danger. I was about to have a Sunday meal with my family when Jan called and said that I should come meet him. Yes, but how would I get there? The safest way was by bicycle, but mine was still at the Utrecht station. When I went to pick it up, I felt the firm grip of a SD plainclothesman on my shoulder.

The arrest felt like a dull blow; I was a little dazed. What do I do now?, I thought. The plainclothesman left me at the Utrecht police head-quarters, but the Dutch police didn’t seem to understand at first that I was a serious case. They put me in a cell with another girl, and I got busy eating some addresses I had on me. When I learned that this girl would be released the next day, I asked her to pass on a message to my parents: “Look for me after the war.”

Before long the SD returned, and the interrogations began: I was shown a photo of the man who had been shot, a terrible photo of him all keeled over with blood everywhere. I closed my eyes and cried a little, and told them that I had nothing to do with it. Still, the foster son had told them certain things. I concentrated on not giving away any information that could endanger the group or the children.

Hetty and I were reunited at the prison in Hertogenbosch where we spent a few tedious days, and then they shipped us to Haaren prison, which housed a lot of Resistance people. The prisoners there kept in touch through the pipes, and Hetty found a way to talk through the vents. She was given a harder time during the interrogations because she had dark features and looked dashingly defiant. I had more of a dumb blonde look, like someone who wouldn’t know anything. Also, she had been seen with Jan, and I hadn’t. Still, the interrogations were never easy, and whenever someone had to go, we would send messages through the pipes like “Be strong” and “We’ll be praying for you.” Afterwards it was always, “Are you all right? Did you make it?”

Haaren had been built as a seminary so the rooms were really monks’

cells with two bunk beds and a little window up top. I found that if I moved the bunk beds to the door, I could stand on top and sing through the open window to Hetty. We would sing to each other in Dutch, and it sounded like folk songs, but we were actually having little conversations. She told me what she had said to the Germans, and I told her what I had said to them, and we finally came up with a story we could both tell about what we had been doing. One time, though, Hetty looked down from the window and saw a pair of black boots, so we figured they had been listening in all along.

After six months, we were sent to the concentration camp in Vught. There was enough food there, and you could get parcels and so on. But then the Germans sent all the women to Ravensbrück, and the men to Sachsenhausen. Those were bad camps. Ravensbrück was overcrowded, and dirty, and you didn’t have enough to eat. The Germans were marching around, well fed, their uniforms new, their boots polished, acting as if the war had already been won. Still, we always thought that the Allies would win the war. Always. It will not take long, we thought. Some weeks. Well, it was many months. But you always believed that in the end the Germans would be defeated, and everything would be all right. We put our doubts and fears into the deep freeze. You couldn’t comprehend what was really happening. It was impossible.

While we were in Ravensbrück, a woman came who had been in Auschwitz. She had somehow convinced the Germans that she wasn’t Jewish, and they let her transfer. She told us what was happening there, and we couldn’t believe it. We gave her extra bread because we felt so sorry for her. Then later the Germans built gas chambers at Ravensbrück, so we saw first-hand.

What I learned in Ravensbrück is that when inhuman conditions go on, day after day, you still can’t help but develop some kind of homely routine. And I found that, in spite of everything, cheerfulness would sometimes break through, especially when we sang our little songs to the others.

At first we sang because we were in prison, and didn’t have anything else to do. We were alone in our cells, so we sang to amuse ourselves. I had taken classical singing lessons, and I remembered many lieder by Schubert and Schumann. There were two or three other girls who passed through who also had a repertoire, and there was one woman who knew many operettas. So I learned from all of them—we would listen to each other through the walls and halls—and the boys above us knew English songs like “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary.” Then after a while, Hetty and I

started taking some of those melodies and making up our own words.

There is one from Vught that we used to sing to the tune of “Anchors Aweigh.” It dates back to the time when Hetty and I had to work in a tire factory the Germans converted to manufacture gas masks. We were on an assembly line, and had to glue the nosepieces down. But we tried to botch things up as much as we could.

Come along, mates, to factory Den Bosch

We make the gas masks here

And we don’t give a damn

If the Krauts don’t like our work

For soon we will be back

In freedom’s arms again.

Hours, days, and months,

Creep along so slow

Unglued masks are all around

But on the line that we glue down

Not one nose will stay put

They all will go kaput!

We’ll never lose heart

We’ll always keep our heads up

They’ll never get hold of us

No matter how sly they are

Ahoy, ahoy, striped women

They’ll pay for this someday

Ahoy, ahoy, striped women

They’ll regret what they have done.

I think that our little songs enabled us to gain some perspective on our miseries. We liked making them up, and the other prisoners liked listening to them. They were just silly songs, but they meant a lot to us.

Most of the songs were meant to be rather entertaining—or so we thought. We usually performed them in a humorous, tongue-in-cheek kind of way. It must be difficult to understand how we could still laugh during those times, but somehow we did. A few years ago there was a reunion of women who had been at Ravensbrück. Everyone asked me and Hetty to sing for them, and so we sang once again.

The last song we ever wrote was when we were leaving Ravensbrück.

This one is more serious, but still we sang it cheerfully:

It’s done; we’re finally free

We couldn’t believe our ears

When they called us to Appell

Have they more tricks up their sleeves?

We know them all too well.

For years we were held captive

Behind the endless wire

No one lost her faith here, ever

For years we longed for our own homes

Then the white vans of the Red Cross

Came to bring us our salvation

From behind the endless wire.

Captives now, no longer

Behind the endless wire

This is the end of all our longing

Of being hungry, cold, and dirty

For the white vans of the Red Cross

Came to bring us our salvation

From behind the endless wire.

What was life like for you after the war?

My family was very happy to see me, and our friends from the group were happy to find that Hetty and I had survived. They’d never given up hope. In fact, Geert Lubberhuizen had put aside a copy for us of everything the

De Bezige Bij

had published since the day we’d been arrested.

Everyone was eager to get on with their lives, and I soon got married. My husband Ate had spent four years in Buchenwald, Dachau, and some smaller camps. I had known his brother at the university, and I remember the day he told me Ate had been caught. But we didn’t meet until 1945, soon after we both had been liberated. He had gone through more or less the same experiences as me, so that was practical—there

wasn’t much to explain. We fell in love, and that was that.