The Heart Has Reasons (12 page)

So you have some regrets about what you did during the war?

No, I would do it again. I would not

not

do it because of the consequences. I believe we did what we had to do. It was our destiny.

When the nazis invaded the netherlands, their hard, unyielding approach must have come as a complete shock to Dutch citizens, who had never experienced anything like it during their lifetimes. Hitler’s way of operating allowed for neither compromise nor mercy, and he had fashioned the Third Reich in his own image. Yet, if we look back to the Eighty Years War (1568–1648), one of the most defining periods of Dutch history, the circumstances of the Nazi occupation take on the quality of a déjà vu. The Dutch national anthem dates back to this time:

A shield and my reliance,

O God, thou ever wert.

I’ll trust unto Thy guidance,

O leave me not ungirt.

That I may stay a pious

Servant of Thine for aye

And drive the plagues that try us

And tyranny away.

The verse recalls the oppressive grip of imperial Spain during which King Philip II sought to purge all heretics—which, to him, meant

non-Catholics. But the Protestant reformer John Calvin—born Jean Cauvin in France in 1509—was extremely influential in the Netherlands during this period, and a band of his staunch followers declared that they would rather die than have a corrupt Christianity forced down their throats. In 1566, Philip II appointed a new regent, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, to bring about law and order in his colonial territory. Destined to become the quintessential villain of Dutch history, this Duke of Alva arrived with an occupying army and demanded that all Dutch sign an oath of loyalty to the Spanish king and the Catholic Church. When several prominent landowners presented him with a petition calling for religious tolerance, he had them beheaded. Such actions, along with the financial damage he inflicted through tariffs and fines, soon led to open revolt.

It was at this time that William of Orange rose up to rally the disgruntled Dutch Calvinists to fight a battle for freedom that would continue for generations. The Spanish Crown sank millions of ducats into this long-distance war of attrition but, in the end, had little to show for it except a ruined economy—their own. After eighty years, Spain finally relented and the Dutch were free to worship as they wished. In the meantime, the identity of the Dutch, and especially that of the Dutch Calvinists, had accreted around that epochal struggle.

In a sense, Heiltje Kooistra is one of the spiritual heirs of the Dutch Calvinists of the sixteenth century who opposed the Duke of Alva. Nearly four centuries later, she and her husband recognized that Hitler represented a threat not only to the Jews, but also to the hard-won freedom from religious persecution that their Calvinist forbears had secured.

As Calvinism moved into modern times, it split into two major sects: the strict

Gereformeerden

(Dutch Orthodox Church) and the more assimilated

Hervormden

(Dutch Reformed Church). The Gereformeerden, also known as “blackstockings,” still number as many as 600,000 today, and, as at the time of the war, remain concentrated in the north, especially Zeeland and Friesland. Farmers by tradition, one can often see them on Sunday, dressed in black, walking to church so as to avoid driving on their Sabbath. They are known for their unwavering adherence to their religious principles, which, most noticeably, involve a rejection of worldly pleasures and pursuits.

Though the blackstockings tend not to associate with strangers,

during the Nazi occupation they were among those most willing to take in Jewish people. During the occupation, many of them felt that in order to be true Christians, they must help, and such behavior became the norm in their communities. In the words of one blackstocking rescuer, “If you didn’t have an onderduiker in your house, you weren’t a proper peasant farmer.”

But the decision to help may also have been influenced by John Calvin’s high regard for the Jews and Judaism. Unlike Martin Luther, who, especially towards the end of his life, excoriated both Jews and Catholics, Calvin had emphasized that the Jews are God’s chosen people and affirmed that both the Hebrew scriptures and Christian gospels are divinely inspired and seamlessly coterminous. That, combined with his writings that recount a God who, working through men, “broke the bloody scepters of arrogant kings” and “overturned intolerable governments,” may have roused these farmers, as well as other Calvinists such as Heiltje and Wopke, to put their faith into action. Indeed, his exhortations to revolt against iniquitous authority had become inscribed as one of the doctrines of the Calvinist Church.

A third, more subtle, factor may also have come into play: saving Jews was a way to know that you yourself were saved. Calvinism puts its faithful into an interesting theological predicament: God has already predestined who will gain divine favor and fellowship and who will be cut off from it, but mortals are not privy to that knowledge. However, an indication of the sealed judgment can be discerned by observing each individual’s words and deeds. True believers are urged to heed the voice of their conscience and act rightly. Though righteousness is, in theory, its own reward, it carries the side benefit of providing a welcome clue that one is among the elect.

This history and theology may help to explain why Calvinists were so highly represented among the people who rescued Jews in the Netherlands. For example, the Gereformeerden, though numbering only 8 percent of the population, constituted about 25 percent of the Dutch Resistance.

In 1942 when the deportations first began, both Calvinist and Catholic churches united in writing a declaration of protest. When the Germans demanded that the statement not be read from the pulpits, the Reform Calvinist Church gave in, but the Catholic and the Orthodox Calvinist churches went ahead anyway. Shortly afterwards, the Nazis arrested 700 Catholics and, later, 500 Protestants, all of whom were considered

Jewish according to the Nuremburg Laws, although they had converted to Christianity. These Catholics and Protestants whom the Nazis had redefined as Jews became part of that great stream of people being deported to Westerbork and terminal destinations in the east.

THREE

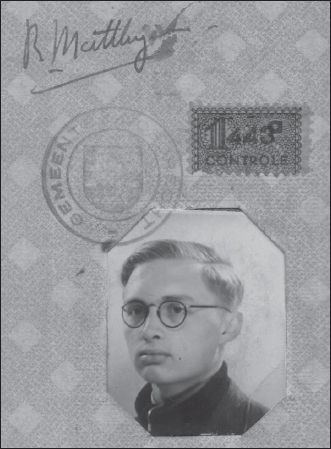

~ RUT MATTHIJSEN ~

CHEMISTRY OF COMPASSION

It is more difficult to

crack a prejudice than an atom.

—Albert Einstein

The resistance did not consist only of big personalities, nor were all of its members stationed on the front lines. Rut Matthijsen is a serene, soft-spoken man, long accustomed to the hush of laboratories through his work as a biochemist. His measured words and studied answers to my questions revealed a lifelong habit of precision and reserve, even as his brown eyes beamed affably behind the powerful lenses of his glasses.

During the war, Rut usually worked painstakingly behind the scenes, applying his emerging scientific skill to a variety of technical problems that beset the Utrecht Kindercomité, and the Resistance in general. His quiet confidence, combined with a detail-oriented, analytical mind, made him especially suited to tackle these challenging tasks. His business acumen also came in handy, as he attempted to raise money to literally “save the children.”

In 1942, I was a college student taking summer courses in chemistry at the University of Utrecht when a fellow student asked me if I would allow the room where I slept to be used during the day. “There are people coming from Amsterdam,” he explained, “and they need a stopping-off place that’s close to the station.” Thinking that he might be referring to onderduikers, I said yes. Curious to meet my transient guests, I went home the next day and found members of the Utrecht Kindercomité with some Jewish children in tow. These people were inspiring—unlike some chem students.

Soon I was spending most of my time helping them transport Jewish children to safe addresses. Once the fall semester started, the group got smaller, even as the number of children who needed to be hidden was increasing rapidly. Many of our fellow students said, “Sorry, I have to study.” But a core of ten or fifteen stayed on. A sense of group responsibility arose quite spontaneously between us, and a tremendous bond formed. I trusted them with my life, and they trusted me with their lives as well. You wouldn’t do anything without thinking about how it might affect the others.

Meanwhile, the Nazis were trying to make over the universities, just as they had made over the government. When they suspended the Jewish professors, there were protests, and the students in Leiden and Delft organized strikes. The Germans then closed both universities, though Delft was later reopened. But in Utrecht we didn’t have a strike—we thought we weren’t ready for that yet. And so, a few months later, all Jewish students were suspended. Still no protest. But by then I had withdrawn from the university to devote myself to rescue work full-time. I wasn’t able to concentrate on my studies, anyway.

At first I did what Hetty and Gisela were doing—delivering children, distributing ration coupons—but such work was more

dangerous when done by a young man, and I’m not sure I possessed the requisite sangfroid. For instance, once when I was on my way to an address in South Amsterdam to bring food to some families that were hiding Jewish children, I was stopped by an officer who was interested in what I had in my suitcase. When he found it was full of cheese and sausage, I was arrested on the minor charge of being a black market profiteer. I might have tried to talk my way out of it, but I hadn’t prepared a story in advance. Then I panicked at the thought that when they found the identification cards in the suitcase, they would turn me over to the SS. To prevent this, I jumped out the window.

That landed me in the hospital with a concussion, and an armed guard outside my door. A Resistance friend arrived, and with his help we were able to persuade the police to drop the charges against me. But I still had to spend another five weeks recovering in the hospital.

I found a more valuable direction for my energies when I teamed up with another group member to do falsification work, which led—surprisingly—to a source of income for the children in hiding. You see, the foster families were, of course, taking on a big responsibility, but besides the danger of it, many of them had very limited resources. We realized we needed to assist them with the children’s upkeep, but we were all students, and none of us had much money. We gave what we could—for instance, my stamp collection brought in 300 guilders—but it wasn’t enough. So that was an ongoing problem.