The Heart Has Reasons (7 page)

While still in Haaren, I embroidered an old piece of burlap using some yarn I had torn from my sweater. In the center was a little pig and bear behind bars, framed by the words: Stand fast my heart in adversity. Those were the words we lived by, but later we took up a more personal motto: Pooh and Piglet always together.

You see, without her—and, I think, she without me—I don’t think we would have made it. We thought exactly the same way. We could always see the humor in a situation, and then it wouldn’t be as bad. And, you know, calling each other Piglet and Pooh—that was marvelous. To be Piglet and Pooh is something abstract. You can say, “Pooh feels unhappy.” You don’t have to say, “I feel unhappy.”

The Germans made us feel powerless. To match our wits with them, to do something about that sense of powerlessness, was very attractive. Once I asked for soap and a wash cloth, and instead they interrogated me again. A Nazi officer named Gottschalk said, “You are a Jew. Wash yourself by spitting in your hands.” I answered very coolly, “Herr Gottschalk, I have exactly as much Jewish blood as you have.” And instead of beating me, he didn’t say anything! So I’m sure he had Jewish blood. I had hidden two boys with the last name of Gottschalk, so I guessed he must be Jewish also. From that moment on, I was given things to wash myself. But I learned what it was like to be treated like a Jew. You were humiliated so terribly. I thought, I won’t let myself be humiliated.

In prison, the boy above me wanted to break out with another paratrooper who was a few cells down. He asked if I could get him a map of the region, and I immediately began working on it. I love challenges. They make me feel fine, especially when you find that you can’t be beaten by them. Whatever happens, you’ll always be the master of it. That’s the way I was thinking.

On our floor, there were a couple of prisoners who came around to bring us our meals. They gave us a lot of attention, because at that moment we were the only women in the prison. So I told these boys I wanted a map, and one of them was able to get me a

marvelous

map which showed the location of the seminary and all the surrounding villages. I then had the problem of how to get it to that British boy. My bed had iron rails, and when I broke one off, it was sharp. So I used that to scrape a little hole next to the vent going up, and I was eventually able to slide that

map right up to him.

Soon afterward, the two of them made their escape, and Gisela and I were immediately suspected of having helped them. The Germans searched our cells, and they discovered the hole I had made in the ceiling. For that, they sent both of us to the concentration camp in Vught, in the south of the Netherlands. Meanwhile, those boys were able to make it back to England, though they had a horrendous time.

At the camp in Vught, the Germans made us work in a big tire factory in Den Bosch that they had converted to manufacture gas masks. We had to make gas masks from six in the morning until six at night, and I sat at the end of an assembly line and molded the nose onto each mask. From there, the masks went into a vulcanization oven where they would be baked and come out hard. But I dug my nails into the nose-pieces while they were still soft, so that when they came out, nobody would be able to breathe while wearing one! For that, I was sentenced to the bunker: the prison within the concentration camp.

In the bunker, I sat with the boys who were going to be shot, and they gave me their last letters to their sweethearts and families. Later, I was able to get those letters through. One boy gave me two buttons from his shirt, and I kept them for the whole rest of the war, when I was able to pass them along to his parents, along with my memories of his final hours.

When the Allies came too near, we were crammed into railroad cars and deported to Ravensbrück, a women’s concentration camp in Germany about eighty kilometers north of Berlin. They let us out at the nearest station, and as we trudged along towards the camp, I picked some flowers from along the side of the road, thinking they would brighten up our barracks. But Ravensbrück was no place for flowers.

When we got there, it was overfull, so we couldn’t even go in. They made us sit on a pile of coal for two days and two nights in the rain. Everyone was black and dirty and dripping wet, but still, there was this kind of laughter inside me, as if it couldn’t be real, as if we were on another planet.

When they let us in, there was a big street, a

lagerstrasse

, and in the evening you had one hour when you could go walking there. And you heard

all

tongues around you: Russian, Norwegian, Polish, Danish, Hun-garian, Romanian, French. At first you just heard voices, but then slowly you started hearing if it was a Hungarian or a Romanian, and then we got to know several of these women, and the Russians sang so beautifully.

The whole time during the war, we kept making up songs. We used tunes that we knew, anything we could think of—folk songs, Charles Trenet, German, English, or Dutch songs. We made up new words, and told the story of what had happened each day. It was a kind of diary all through the camp time. Gisela sang a lot, and she sang very well, and I could always, very easily, sing in harmony with her. She would sing high and I would sing low. The moment she started, I quickly made the second voice, and that’s the way the two of us would sing.

The sad thing was that very few people sang with us. It was always a big mass of people being unhappy. There were lots of them who didn’t want to sing. They liked us to sing

for

them, but they didn’t come along with us on it.

And I can understand. When we came to Ravensbrück, it was like hell—all these skeletons clinging to you because perhaps you had something for them to eat. It was really

unbelievable

when you came in. There were about 50,000 women in a camp built to hold 5,000. From all nationalities.

I had always wanted to go around the world and meet all kinds of people, and there I thought, I needn’t here: I have them all. The Allies were so near that we said, “Two weeks and it will be over.” But that is not what happened. We arrived in September of ’44, and it wasn’t until April of ’45 that it ended.

We had to live in dirty barracks with the lice and sleep on hard mattresses filled with a little fetid straw. The thin blankets were never enough, so we would cover ourselves with rags. During the day, many of the women had to do shoveling or other hard labor, but we worked at the Siemens factory, which at least was indoors. For lunch we would get a watery soup with some cabbage in it, and for dinner, more soup and a piece of hard bread. We were always hungry, and cold too—it often snowed during the winter.

But somehow I accepted my fate when I was in the camps. I wasn’t arrested for nothing—I had

done

something. I met many Jewish people in Ravensbrück, and we had exactly the same life. But for them, it was much worse. They were being destroyed solely because they were Jews. And that was awful! There were lots of them who died there. In December ’44 they installed gas chambers, and each week, all the old women who could not work any longer were put onto trucks and taken away. Then on Sunday night, the others waited for us to sing for them. We thought, we can’t do it. But then we thought, we have to. One must simply go on.

I got a terrible ear infection in Ravensbrück, and Piglet—this is

Gisela—always managed to get a little scrap of a letter to me in the infirmary. Those letters were marvelous. I want someone to tell me, why do they move me so? I still have them, and whenever I read them now, I always start to cry. She would write, “It’s my mother’s birthday today, and I’ve been singing her favorite songs the whole day long. Come with me to the woods and we’ll kick through the leaves . . .”—always things like that, you know? She somehow managed to get them to the Dutch nurse in the infirmary, who would then slip them to me.

So we had all kinds of ways of getting through: the singing, the letters . . . Did you know you can make dominoes from bread? And if you want to sew, tear the threads from your clothes. My friend once had a Sinterklaas present made for me by the Polish women, who were very good at sewing. You had to pay them with bread to do something like that.

There was a group of Greek partisans who had fought in Albania together with the English army. They were arrested and had been sent a long way by train to Ravensbrück. They spoke some French, and we did too, so we would sit around at night telling stories as we picked lice from each other’s hair. We had lovely conversations, and when we talk now with other women who had also been in Ravensbrück, their experience was so entirely different from ours. They only know about rain and dirtiness, and we only know about the

exciting

stories that we heard there.

Yes, our morale was higher than many of the other prisoners, but we were just young and bold with no responsibilities. There were a lot of Communist women there whose husbands had already been shot. There were so many who already had such sad things behind them. But we were just sorority girls. It was

easy

for us to live through it. Because of our good spirits, we were able to cheer up other people. And that makes

you

feel better, for you can’t cheer someone up without being cheered up yourself. It’s not that we had a good time there, but it was a very

special

time. You can never compare it with ordinary life because it brought you to the limits of what you could endure . . . and still there was a song to sing.

Each morning and evening we would line up for the Appell. We had to stand at attention for hours in the cold as they called out our numbers. Someone would be missing, and they would kick us, and hit us, and start all over again. Then one day I looked up and saw a gull winging across the sky. Unbelievable! Where did it come from? Where did it go? To see that gull with the sun on its wings . . . it was like a vision of another world. For truly in Ravensbrück you had the impression that you were no longer on this earth.

Towards the end, the Germans knew they were going to be defeated,

and all their devils broke loose. They stopped feeding us, and day and night they were burning the dead bodies. I shared a bunk bed with four other women, and when I woke up one morning, the Hungarian girl who had been sleeping next to me was dead. The worst of it was that you didn’t really react any more—you just said, “Oh, she’s dead.”

At the beginning, we didn’t think that we ourselves would turn into skeletons—but we had. I thought, it’s a pity for my parents. It will be hard on them if I die, but Gisela kept believing that everything would be all right. That really helped me.

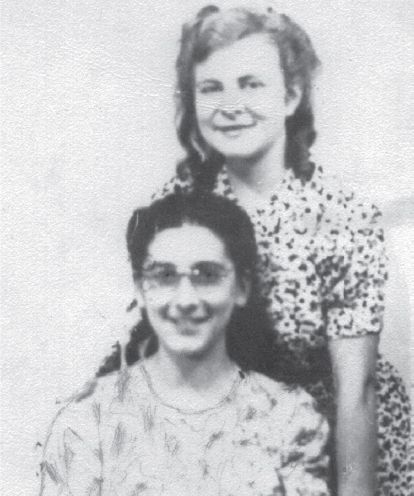

Hetty and Gisela in Sweden after the liberation.

We were liberated on 28 April 1945 through an arrangement that Folke Bernadotte, the Swedish diplomat, made with the Germans. It was incredible; absolutely incredible. A Red Cross official who came into the camp talked to us, and it was so fantastic to have someone talk to you like a human being.We were given fresh bread and lentil soup, and there were doctors on hand to take care of us. My need was not the most urgent, although I weighed just less than forty kilos—that’s eighty-eight pounds! Then we were taken to Sweden by van and railroad and ferry.

When the ferryboat arrived in Malmö, we hobbled down the gang-planks, squinting with delight in the springtime Swedish sun. Despite our exhaustion, we smiled and waved at the welcoming party of Red Cross workers, and soon were plying them with questions: “How long will we be here?” “Can we contact our families?” “Is the war really over?” When someone asked, “Will we get a hot bath with soap?” the answer, incredibly, was yes.

We learned that there was still a bad food shortage in the Netherlands, so we wouldn’t be returning home anytime soon. Many people

coming out of the camps had tuberculosis, and I found out that I was one of them. So I had to part with all my friends, and go away to a sanatorium near Stockholm.

It took a long time before I could accept that life should go on. Everything was all clean and white with Swedish nuns in their starched caps coming in to adjust your pillow. But it all seemed make-believe somehow, and when I looked in the mirror, I hardly recognized myself. When I really had to think about something, I thought myself back into the concentration camp. That seemed more real to me than freedom.

It was hard to be apart from Gisela, but I thought, I might as well make the best of it, since my recovery will take a long time. They gave me a dictionary and some books, and I thought, here’s an opportunity: I’ll learn Swedish. I was in my bed all day, so there was also time to knit things for all my little nephews and nieces who were born in the meantime. I had a strong will to live, so it was not so difficult.

There was no communication between Sweden and Holland for months, and no one was traveling back and forth. At the end of August ’45, the first camp survivors began to return, and by that time my family knew I was alive because I had a nephew who went to the Dutch embassy in Stockholm, and he saw my name on a list of Dutch women who had been liberated from Ravensbrück.