The Heart Has Reasons (3 page)

Two extreme Jewish responses were therefore seen early on. In Amsterdam, where the Jewish population was concentrated, more than a hundred Jewish people committed suicide during the first weeks of the occupation, putting their heads in gas ovens, or jumping out of windows rather than be subjected to what they feared the Nazis had in store for them. There were also some Jews who, either alone or in gangs, directly fought the Germans with whatever weapons they could get their hands on. This was tantamount to suicide, considering the tens of thousands of heavily armed German combatants.

The majority of Holland’s 140,000 Jews adopted a wait-and-see attitude, however, as did the rest of the Dutch populace. The easiest option was to go about one’s life as before, keep a low profile, and hope that the Germans had the sense to realize that there was no point in arresting quiet, law-abiding Dutch citizens. The Germans were quick to exploit such hopes; their deceptive policies led Jews to believe that decent treatment was possible if they complied fully. Still, Dr. Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the forty-eight-year-old Reichskommissar put in charge of the Netherlands by Adolf Hitler, stated the Nazi position quite clearly in an early public address: “We shall hit the Jews wherever we find them and those who side with them will bear the consequences.”

Less than five months into the occupation, the Germans required all government employees to fill out an “Aryan attestation.” This form called for detailed information about the applicant’s family background, especially any Jewish ancestry. Though there was some protest, not just from the government employees, but also from several churches and universities, in the end, all but 20 of the 240,000 Dutch civil servants dutifully signed and returned the form. Dutch historian Peter Romijn reports:

From the German point of view, the registration went as planned. Anyone who was of two minds about signing the attestation, and who sought guidance from their superiors, found none. The Supreme Court refused to sanction refusal to sign, most members arguing that in view of the state of war the Germans

had the right to take such measures. Because of the position taken by the Secretaries-General and the Supreme Court, any chance of making a collective protest was lost.

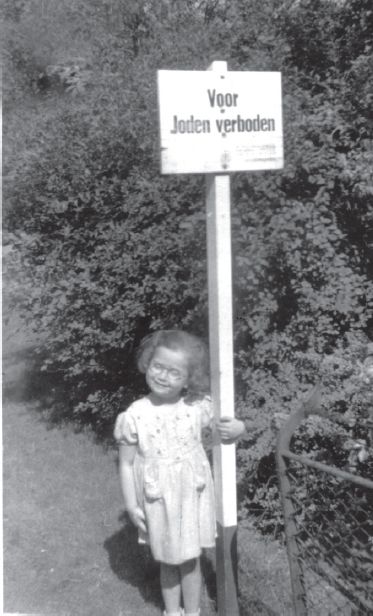

Soon after demanding the Aryan attestations, the Germans began to issue the first of hundreds of regulations aimed at denying Dutch Jews their civil liberties. In the beginning, the devil was in the details, sometimes ridiculous details: “Jews cannot walk on the sunny side of the street.” Hardly worth fighting against, but greater restrictions followed: “Jews cannot go to the park.” “Jews cannot attend the cinema.” “Jews cannot play sports.” By the time the deportations started two years later, Jews could not travel or change their place of residence. They were prohibited from marrying non-Jews; they could not even visit non-Jews. They could not drive cars or make telephone calls. Many were barred from practicing their professions. As they became increasingly stigmatized and desperate, they also became increasingly isolated from non-Jews. Through such means, the Nazis sought to establish the Jewish people as a subhuman species, repellant and deserving of persecution.

A Jewish girl in the Netherlands standing next to a

“Jews Forbidden” sign. Courtesy of the Netherlands

Institute for War Documentation.

Who was enforcing these regulations and carrying out the Nazi agenda? When the rescuers recount roundups—known as

razzias

—and other operations, there was no single generic Nazi group that carried them out, but rather a startling array of NSB storm troopers (“Black Police”), German common police (“Green Police”), Waffen-SS (SchutzStaffel, meaning, “Defense Echelon”), Gestapo (“Secret State” police), SD (German intelligence officers), Sipo (German security officers), Krpo (German criminal police), Wehrmacht (German soldiers), and still others such as detectives,

espionage agents, and the Dutch police, who were all taking their orders from the German authorities. Holocaust scholar Christopher R. Browning has remarked that in the Netherlands the bewildering assemblage of Nazi groups essentially competed with each other to see which could most quickly do away with the Jews.

The NSB storm troopers require special explanation, for they were not Germans at all, but Dutch. The Nationaal Socialistische Beweging was a Dutch fascist party, founded in 1931, dedicated to establishing a powerful central government with emphasis on order and discipline. During the occupation, NSB members often proved to be more dangerous than the Germans because they spoke the language, knew the neighborhoods, and served as eyes and ears for the Gestapo. Many a fledging rescue attempt ended in tragedy due to an NSB informer. Such NSBers and others wanting to make easy money turning in their co-citizens, took the Gestapo up on its offer of seven-and-a-half guilders—which had the buying power of about fifty dollars today—for each Jew whose whereabouts they betrayed.

Before the war, the NSB had been able to capture only about 8 percent of the vote; after the Nazis arrived, however, their leader, Anton Mussert, formed an alliance with the German occupiers and suddenly became extremely powerful. He and his followers enthusiastically assisted the Nazis in all of their operations, especially the rounding up and deportation of Jews. Within a couple of years, the Nazis had made the NSB the only legal political party and declared Mussert the leader of the Dutch people.

In January 1941, the Germans announced that all Dutch citizens over the age of fifteen had to register, and from then on carry identification cards. This request was, as Holocaust historian Raul points out, “the first step to ensnare the Jews in a tight network of identification and movement controls.” Dutch historian B. A. Sijes estimates that out of a Jewish population of 140,000, only a few dozen Jews refused to register.

By this time, Jews were increasingly being taunted and beaten up in the streets, not yet by the Germans themselves (who were covert and methodical about carrying out their plans), but by NSBers. On February 11, some of them entered the Jewish Quarter of Amsterdam and proceeded to attack people at random and break the windows of storefronts. This time, however, a Jewish

knokploeg

—the Dutch word for a kind of vigilante gang—attacked the attackers, and one Dutch Nazi by the name of Hendrik Koot was seriously wounded.

Members of the Nationaal Socialistische Beweging (NSB) marching in a rally in the Netherlands. Courtesy of the

Netherlands Institute for War Documentation.

The following day, the Nazis ordered the establishment of a Jewish Council to act as an intermediary between themselves and the Jews. They appointed the chief rabbi of the Ashkenazi community, as well as its president, Abraham Asscher, to lead the Council, along with one of the rabbis from the Sephardic community. When both rabbis declined, Asscher suggested Dr. David Cohen, an influential, thoughapparently not widely liked, secular leader in the Jewish community who was already head of an agency that assisted Jewish refugees. (Cohen had snubbed the rabbinate by hardly including any rabbis on the board of this and another major Jewish organization that he had founded.) And so Asscherand Cohen chaired the Council, which immediately began to issue announcements to the Jewish community based on orders from the Nazis, the first being that all Jews must surrender their weapons.

On February 14, even as the death of Hendrik Koot was receiving wide coverage in the Nazi-controlled newspapers, another incident happened in South Amsterdam. Some members of the Green (German) Police surrounded Koco’s, a popular Jewish-owned ice cream shop believed by the Germans to be a base for a Jewish

knokploeg

. The previous week, after the shop’s windows had been smashed, its owners rigged up a contraption to spray ammonia at any unwelcome intruders. When the device went off as some German police entered, the owners and others present were arrested. But this was just the start of the Germans’ retaliation, which was always much more severe than the incident that triggered it.

On Saturday, February 22, when many Jews were quietly observing the Sabbath, hordes of Green Police cordoned off the Jewish Quarter and arrested hundreds of Jewish men, dragging them off the street or pulling them from home and synagogue. After being marched in columns to Jonas Daniël Meyerplein, a public square, the men were forced to run through a gauntlet of policemen swinging their truncheons and then ordered to squat for hours with upraised arms. The next day, the police raided again, bringing the total number of arrests to more than 400.

This first brutal roundup sent shock waves throughout the entire country. British historian Bob Moore writes, “For the first time, the Germans had shown their hand: the tactics of the oppressor, which had been so evident in Germany since 1933, were now being applied in the Netherlands.” The Communist party called for a protest strike, an idea that spread in a great flurry of whisperings to other groups and workers of all kinds—not only in Amsterdam, but in Utrecht and elsewhere. Though the Communists had initiated several previous strikes in opposition to Nazi policies, this was the first time that a strike had been called specifically to protest the Nazis’ treatment of the Jews. Thousands of workers walked off the job, bringing shipping, unloading, transportation, and other services to a standstill.

The Nazis responded with a crackdown that resulted in at least seven deaths and the arrest of more than a hundred strikers. The next day, however, the strike grew bigger. Thousands of longshoremen, metal workers, and others refused to go to work, severely crippling the economic and industrial infrastructure that the Nazis were so vigorously exploiting. In the armament industries alone, more than 18,000 workers were absent from the factories and assembly lines. However, when the Nazi authorities claimed that the strike was being instigated by the Jews and threatened to arrest and possibly shoot 500 additional Jews the following day, the strike’s leaders, heeding advice from the Jewish Council, called an end to it.

The February Strike was the only mass protest over the plight of the Jews to be carried out in all of occupied Europe and perhaps the only mass strike in history on behalf of a persecuted minority. For many Jews, it was the most cherished moment of the war, providing a tangible sense of solidarity with their Dutch co-citizens that cut through the isolation and denigration the Nazis had imposed on them. Still, it was ultimately

ineffectual.

Jewish men arrested on February 21, 1941 and made to squat for hours at the Jonas Daniël Meyerplein with upraised

arms. Courtesy of the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation.

During this winter of 1941, Jews in the Netherlands must have been desperately weighing their options. Clearly “fight” was futile; what about “flight”? Many Jews were thinking about leaving the country or going into hiding, but both possibilities were fraught with difficulties. All legal means to emigrate had been cut off by the Nazis, and those who tried to make a run for it found danger in every direction.

Holland is surrounded by the sea to the north and west, and flanked by Germany to the east. To the south lie Belgium and France, both of which had been invaded at the same time and were also under German occupation. To pass through these lands, money would be needed to pay off the right people, and even then there would be no guarantees. Nevertheless, about 1,400 Jews escaped to Switzerland via Belgium and France, and another 1,300 managed to get to Spain and Portugal. To the west of Holland is the open sea, and by crossing it one could reach England. Some Dutch tried to do this in small boats and canoes, but only about 200 were able to make it without being intercepted by German patrol boats.