The Heart Has Reasons (9 page)

I am also helping Beit Lohamei HaGetaot, the Ghetto Fighters’ House in Israel, to create a Dutch exhibit. Some time ago, a lady phoned me and said, “For so long I’ve been looking for you, and at last I have found you!”

I said, “I think you have a nice bright voice, but I haven’t the faintest idea who you are.” And then she came to visit, and I opened the door and she said, “Oh, exactly the same eyes!” She walked into this room, and said, “Don’t you remember? You were standing under the clock at the Amstelstation and I gave you my two little children—a boy and a girl.” I said, “I stood so often under the clock at the Amstelstation.” But as we talked, the memory slowly came back to me.

She told me how the people who had escaped from the ghettos and camps in Poland went to Israel and formed a kibbutz in the Western Galilee. When they were still in the ghetto, they had promised each other that those who survived would preserve all the things they had made and written—diaries, paintings, knitting, everything. So in 1949 they built the first Holocaust museum. But it was only about the people of Eastern Europe, and this woman, who is from Holland and spent time in a camp, thought it should include the Dutch too. She asked if I would get involved, and we started to do it together. Many of my things will be on display, like that embroidery of Piglet and Pooh.

There was an unveiling recently of a very special stained glass window that was installed at a church in Vught. The window symbolizes the solidarity between the women who were in the concentration camp there. You see one woman lying on the ground, and the other ones helping her to get up. It’s a beautiful window, and when it was first shown they had a program that included music that had been sung in the camps. A choir sang some of the songs that Gisela and I had made up. My granddaughter was there, and it was very emotional for her. For the first time she could picture how life was for me when I was a young woman—as she is now.

How can we prevent something as terrible as the Holocaust from happening again?

It already has. Not on the same scale, but we’ve already seen the Khmer Rouge regime massacre its own people in Cambodia, the Iraqis gas the Kurds, the Serbs in Bosnia butcher the Muslims, the Chinese slaughter the Tibetans. And just a short time ago, the Hutus in Rwanda took up their machetes and hacked almost a million Tutsis to death! Who did anything about it?

Recently I was asked to speak at a college in Israel. In the audience there were both Jewish and Arab students, and at the end an Arab boy raised his hand and asked, “Would you have helped my people if they were in trouble?” And I told him that at that time it was the Jews who needed the help. If it had been another group, I think I would have helped

them also. You can’t let people be treated in an inhuman way around you. Otherwise

you

start to become inhuman. It’s a simple notion, but people tend to care only about their own people, don’t they?

Yes, and it saddens me.

. . .

So, if I, as a Jewish person, say, “Never again,” thinking

only of the Jews, I probably won’t take action on behalf of other groups.

That’s right, and one group alone might not be strong enough to protect themselves from a bad situation; everything depends on their getting help from the others.

Any other ideas as to how we can help bring about peace and justice in the world?

I think only by being an example yourself. That’s the only way to teach anybody anything. . . . Shall I make you a bowl of soup?

Like all children of those who barely escaped the holocaust, I have often asked myself the “what if” questions, the most prominent being: What if my father and his family hadn’t made it out of Poland? When considered deeply enough, these questions can become as confounding as Zen koans. For me, they also conjure up the little bit of pre-Holocaust family history I've been privy to.

My father once told me that after his family had departed their village of Glowaczow and were waiting to leave Poland from Warsaw on the ocean liner

M.S. Batory

, they stayed for a few days with a cousin who tried to persuade them to remain another week. “It will be so long before we see each other again,” she pleaded. “Why not take the next ship?” My father, only a boy at the time, tugged at his mother’s skirt and insisted that the family stick to their plan. As it turned out, not another passenger ship left Poland until after the war was over and nine out of ten of Poland’s 3.3 million Jews had been murdered.

My father went on to enjoy a full and comfortable life in the United States. But without that ship, his life would have ended in another era, in another country. It would have ended before he learned to speak English, before he worked in the clothing store with my grandfather, before he enlisted in the U.S. Army to go back to Europe and fight the Germans. It would have ended before he went to Brooklyn College on the GI Bill,

before he met my mother there, before my sister and I were born.

If not for that ship, he would have suffered exactly the same fate as all my other relatives in Poland.

Or maybe, just maybe, he would have run across someone like Hetty or Gisela. . .

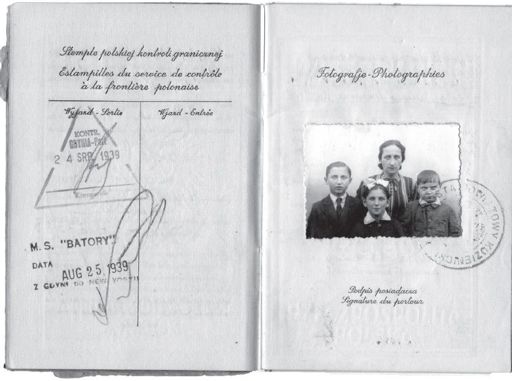

Pages from the passport used by Lillian Klempner to emigrate to the United States with her children, including the

author’s father on left. The stamp indicates that passage took place on August 25, 1939 aboard the M.S. Batory, the

last passenger vessel to leave Poland before the Nazi invasion a week later.

TWO

~ HEILTJE KOOISTRA ~

FAITH LIKE A ROCK

Whomever the Lord has adopted and deemed worthy

of His fellowship ought to prepare themselves for a hard,

toilsome, and unquiet life, crammed with very many and various

kinds of evil. It is the Heavenly Father’s will thus to exercise

them so as to put His own children to a definite test.

—John Calvin

To fully understand heiltje kooistra’s narrative, some background is needed about the “hunger winter”—the period towards the end of the war when the Nazis reduced, and then cut off, the food supply to those 4.5 million Dutch still under their control.

Early in the occupation, the Nazis issued ration coupons that the Dutch had to present when purchasing food. Though they appropriated all the choice foods, the rations were still considered adequate for

nutrition, if not for taste. By November 1944, however, they lowered the rations to 1,000 grams per person, or just over two pounds per week. The result was widespread undernourishment, especially in the densely populated cities of Amsterdam, Utrecht, and Rotterdam where people did not have gardens or livestock. Processions of hungry people began journeying into the farmlands to beg or barter food directly from farmers.

In December 1944, the ration was decreased to 500 grams per person, per week. “So this at last is the phantom of starvation,” read a newspaper article at the time. “It attacks unexpectedly, in a cool and businesslike manner. Older people feel it first in their hearts, for they see that their children are hungry, really hungry, and there is no remedy.” A later article referred to the eerie silence that had fallen over the cities: “Those who are hungry shout, but those who are starving keep still. The traffic has stopped, all enterprises are paralyzed. Footsteps are smothered by the thick snow and this immense silence is penetrated by one single thought: that of the daily bread which is lacking.”

By February 1945, the ration had been lowered further to a life-threatening 350 calories a day. Before Red Cross packages and U.S. food drops brought relief in early May, more than 18,000 Dutch people had starved to death.

....

I first heard about Heiltje Kooistra from her friend Hetty Voûte, who told me that I

must

talk with her. At the time of the Nazi occupation, Heiltje and her husband Wopke lived with their three young daughters in a small house in Utrecht, a house that soon became the scene of much secret activity. Now in her eighties, Heiltje still lives in that same small house on the same quiet street.

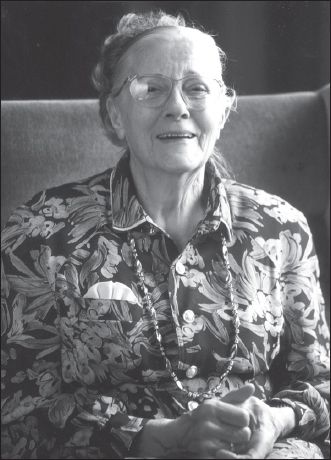

She came to the door smelling of soap and rosewater, a tall woman in a vivid blue dress. Her face was broad, without any sharp angles or gauntness, and her hands, as she offered them to me in greeting, were plump and soft. My first impression was that of a sturdy woman who was also very gentle.

As she told her stories, Heiltje seemed, at first, to be all about practicality, but a different side came out when she recounted the fun she and her husband used to have with their secret guests after the day was done. And something extraordinarily different emerged when she began to speak about her religious beliefs, and how these came to bear on her rescue activities.

As I was leaving the house, she showed me a book by Clara Asscher

Pinkof, a widely read Dutch author who survived the Holocaust and later wrote about her experiences. This book,

Star Children

, is about the Jewish children of Amsterdam, most of whom did not live to see the liberation. Heiltje opened the thin volume to an epigram: “If you trust deeply in God, you can draw to yourself a miracle.” Below, the author had written, “Wopke and Heiltje have brought a miracle close at hand.” In the story that follows, Heiltje reveals something of the contours of that miracle.