The Heart Has Reasons (29 page)

Wartime portrait of Gerard Musch.

At first, my parents objected, because it was so dangerous, but later they became very supportive. Gerard and I fell in love during those months and we even got engaged, but our happiness was cut short when he was arrested in May ’44 and sent to the concentration camp in Vught. Dick Groenewegan was also arrested, but he managed to escape, and made his way back to our house to hide. Naturally, I was terribly worried about Gerard, but my mother would say, “Mieke, just take one day at a time.” She really lived by that and convinced me to do the same.

As far as our own safety and the safety of our young charges, we were fortunate to have a contact in the police department who would warn us when there might be a raid. Then we would hide our Jewish friends in the bathhouse, in the cellar, and some we’d put in the church behind the big pipe organ or up in the belfry. The Germans never caught any of the children at our house, and only two of the children hidden by the NV ever fell into the German hands. In all, we were able to save about 250 of them.

Sometimes I think my war started after the war was over. Gerard had suffered so much in the concentration camps that when he came back, he was a changed man. We learned that Jaap had been executed by firing

squad after having been tortured very badly, and that Joop Woortman had been killed as well. They had even arrested and tortured Rev. Pontier.

Jaap and Gerard Musch during the war with three Jewish teenagers they had placed in “safe addresses.”

So what did we do? We tried to move forward. Gerard began to work and to study as hard as he could. We got married and had our children, but there was a lot under the surface. It’s hard to explain—we’d made it through so much, but it was only after the war that we began to feel its full effects.

Gerard started drinking. When he eventually sought treatment, they tried to get him to talk about what happened to him in the camps, but he’d blocked it all out. He had spent the last year of the war in Sachsenhausen where men were strapped to blocks and whipped or put in straitjackets and starved. How can you put that behind you without even talking about it? Instead he became an alcoholic.

He was a good husband in many ways, but finally I had to choose between what was best for the children—we had seven of them by then, including one who is deaf—and his continuing to live here with us. I have no doubt as to the origin of his problems.

The older I get, the more I think about those war years. They never leave you.

Why do you think so few people helped?

For the same reason that there would be so few today. Nothing has changed. And the same kind of men continue to stoke the machinery of war. Sometimes there’s a sort of rage within me. I want to shout: “It’s ridiculous what you’re doing! Why do you use people as soldiers to kill other people!”

You say nothing has changed, but we don’t have German soldiers outside shooting

Jewish people.

Ah, well, give the German a rifle and he will shoot. And perhaps you could say, “Give the French,” or “Give the Dutch.” It depends on how you get them behind your bad ideas, you know? The masses are easily manipulated, and so are their violent urges. . . . Is this too depressing for you?

No.

People say “Never again,” but just because they say that doesn’t mean that they’re any more aware than the Germans were when Hitler was making his debut. How many people who read the newspaper can tell the difference between propaganda and fact? How many can see through the bad politicians? There’s such a lot of dirty politics.

So you’re saying we mustn’t underestimate our capacity to be misled

. . .

Yes, or to do the wrong thing when we think we’re doing the right thing. We have it good here in Holland, and we are proud. But in many ways we shouldn’t be, we shouldn’t be . . . especially if you look into our history. I recently read a book about the slavery in South Africa at the time it was a Dutch colony. It makes you feel really ashamed to be Dutch. And if we have done many bad things in the past, why should we think that we are so much better now? You see what is happening with people who come here from Africa because their lives were in danger in their own country. Some Dutch complain about the social assistance these people are getting, as if it is being taken out of their own pocket. They might not say directly to you, “I hate blacks.” But you feel in the way

they talk about them that if they had a chance, they would drive them out. Sometimes people, like cab drivers, will call them racist names. They fall silent when I say, “I have a black son-in-law.” I tell them, “We’re all part of the same human family.” We have to watch the way we think. I sometimes find myself stereotyping people—it’s a startling discovery to make about oneself.

When you have had several bad experiences with people of a certain type, you must be very careful to not begin thinking about all of them like that. My husband suffered terribly at the hands of the Germans, but he didn’t hate all of them—he hated the people who had caused the suffering.

When we educate our children about the Holocaust, it’s not enough to tell them about the horrors—we have to tell them that it should not happen that way again. That hate doesn’t bring peace, and that violence doesn’t bring peace, and that you need to be strong in mind and think things over before you get a weapon to use against the one you call your enemy.

It sounds like you believe in nonviolence.

Well, that’s simply the message of Jesus: love your neighbor, even love your enemies. His words are more real to me than the things of this world. Yet I have many doubts. Very many. I read in my Bible every night, and as I read I have the feeling that I know very little. Jesus came to bring peace, yet there is still so much bloodshed in the world. Every time I turn on my TV, I see that we are a violent, killer people. The more we hate, the more we become what we hate.

I am troubled by the misguided, sometimes terrible, things that are done in the name of God or Jesus. Often it seems that people are practicing tribalism, not religion. Then there are those who think they must fight falsehood with their truth, but they don’t want to fight the falsehood

within

their truth. They are pristine, while the others are evil. But the devil is no respecter of religion or nationality. As Solzhenitsyn has written, the line separating good and evil doesn’t move along national borders, or between political parties, or social classes. It passes through every human heart—through all human hearts.

In prewar Germany, there were those who opposed Hitler. Some stayed and tried to alter the fate of their country; others fled. I remember immigrants to Holland who were good Germans and aghast at what was happening to their homeland.

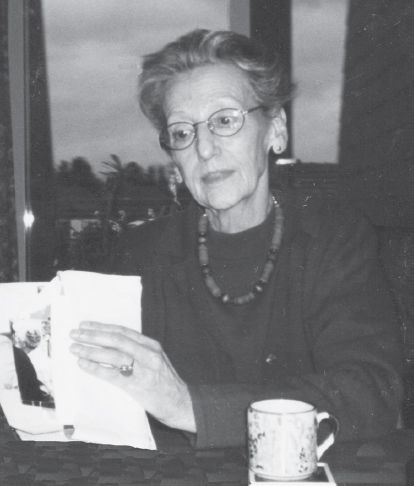

Mieke Vermeer as an elder.

It’s always a fight trying to uphold the truth, but truth is not the sole possession of any one person or group. I really don’t understand the religious fanatics, be they Jews, Christians, or Muslims, who are so sure that only what they think is right And I don’t understand how you can fight for a religion with weapons.

And then the victims just hate you

and your religion more. When my

father was growing up in Poland

in a little town about fifty miles

from Warsaw, peasants would

assault Jews on Christmas and

Easter. He had to stay indoors to keep from getting beaten up by these so-called

Christians. Now, when he sees a crucifix, it nauseates him,because to him it’s a symbol

of hate, not of love.

Hmm . . . I wonder what he would think about you talking to me—someone who has come to believe in Christ, and yet who helped rescue Jewish people.

I think he would consider you an exception; someone who wouldn’t have taunted him

when he was a child.

God forbid. [

deep sigh

]

Do you have any advice for younger generations as to how we can prevent something as

terrible as the Holocaust from recurring?

Do what you can, where you are, with what you’ve got. There are many little holocausts going on in the world, and all around us. Step in wherever and whenever you can.

What do you mean “little holocausts”?

I’ll tell you about one I once heard about from a social worker: A nine-year-old girl was kept locked up in a closet by her legal guardians, who were crack cocaine addicts. When the social worker opened the door, she found the girl lying there half-starved. Her clothes were soiled, there were lice in her hair, and she had cigarette burns on her body. That little girl was trapped in a little holocaust. If my friend had not stepped in, I don’t know what would have happened to her.

Some might think that it cheapens the Holocaust to compare the children of drug addicts with Jewish children during the occupation. But what could be cheaper than the Holocaust? If you were the wrong religion at that time, or if you were a gypsy, or gay, or disabled, your life had no value. I believe the best way we can honor the memory of those who died during the Holocaust is to come to the aid of innocent people who are suffering now. Especially children.

During the Nazi years, people didn’t always want to know about the harm being done to children. They would turn away because they dreaded what might happen to them if they tried to do something. But today, there’s no excuse. There are many people, very well off, who don’t want to be bothered. That’s why I believe in comforting the afflicted, and afflicting the comfortable.

What do we do about people’s cynicism? Joni Mitchell asks in one of her songs,

“Is justice just ice? Governed by greed and lust? Just the strong doing what they can.

And the weak suffering what they must?”

We lived through that. It was very frightening, but we weren’t cynical about it—we took action. And action is still needed today. The prophet Amos says, “Let justice roll down like waters,” but that isn’t something God can do alone. He needs our help.

Where do we start? Besides the “little holocausts” you speak of, there are unprecedented

threats such as the possibility of nuclear war or environmental catastrophe brought on

by climate change . . .

Each generation has to face a new set of problems, but God also gives us the power to solve them. Think of what a terrible problem Nazism was in my day. Now it’s history.

How did Yad Vashem come to honor the members of the NV?

A group of the “hidden children” went to them, including Ed van Thijn, who had become mayor of Amsterdam. We told him that we didn’t want any special recognition—that we were more than rewarded by the fact that he and the others had survived and found their way in the world. But they were insistent and filled out a lot of paperwork testifying to what we had done. In the end, all twenty members of the NV were honored by Yad Vashem.