The Heart Has Reasons (28 page)

He would also randomly slip yellow armbands to people during deportations from the Schouwburg, instructing them to put the armbands on during the ride to the transfer point and then to ask the conductor to be released. Since the armbands showed that the deportees were on the staff of the Jewish Council, their arrests would appear to have been a mistake, and the conductor would dutifully let them go.

The reader may wonder what happened to Walter Suskind—a sad story, but one worth telling. On the eve of Rosh Hashanah, September

29, 1943, the last razzia was carried out in the Netherlands, resulting in the arrest of thousands of people. Among them were the remaining staff of the Jewish Council, including Asscher and Cohen, who were taken to Westerbork and informed that their services would no longer be needed. Suskind managed to evade arrest, but his wife and daughter, as well as his mother and mother-in-law, did not.

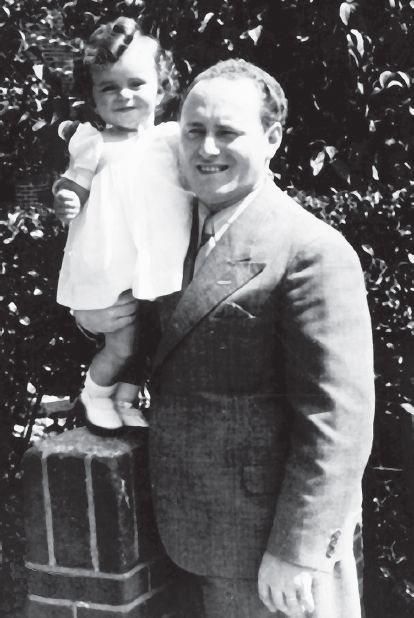

Walter Suskind with his little daughter. Courtesy of the Ghetto

Fighters’ House (Beit Lohamei HaGetaot), in Israel.

Piet begged Suskind to dive under and try to help his family from the outside, but Walterthought that he could be more effective from within. Even as the Nazis had established the Jewish Council in Amsterdam to carry out their commands, in Westerbork, also, a handful of Jews presided over a cruel semblance of self-government. Suskind hoped that, in collusion with these Nazi-appointed Jewish administrators, most of whom were also German, he could save not only his own family, but many other Jews as well.

Unfortunately, after Suskind reported to Westerbork, that did not turn out to be the case. Piet recalls, “Over there, he wanted to do what he did in the theater: play around with the index cards, and allow people to escape. However, those in charge did not dare.”

Suskind was able to talk his way out of Westerbork using his connections, but he could not get his family released. He returned to Amsterdam and continued his rescue activities, somehow managing from a distance to get other people released through the manipulation of official records. He was also able to delay the deportation of his family for a full year. Before they boarded what turned out to be the last transport ever to leave Westerbork, he returned to the camp to go with them. They all died shortly afterwards.

NINE

~ MIEKE VERMEER ~

STARING TRUTH IN THE FACE

If things are ever to move upward,

someone must take the first step and

assume the risk of it.

—William James

Of the handful of known resistance groups dedicated to helping Jewish children, several had their origins in the Calvinist Church. Mieke Vermeer, while only a teen herself, became involved in the main one, named, with a touch of irony, the

Naamloze Venootschap

—“Limited Liability Company.”

The seeds for the Naamloze Venootschap, commonly known as the NV, were planted by Rev. Constant Kikkel in Amsterdam at the time

when two teenagers of Austrian-Jewish background in his congregation, Marianne and Leo Braun, were called up for deportation. The following Sunday he preached a sermon in which he guardedly brought up their dilemma, and two young men came forward after the service, brothers Jaap and Gerard Musch, to say they would try to find hiding places for them. Together with a friend named Dick Groenewegen van Wijk, the three began their search, not only to help the Brauns, but to find hiding places for other Jewish children as well.

Success came when they followed up on Rev. Kikkel’s suggestion to talk to Reverend Pontier in the southern province of Limburg. Pontier recognized the importance of their mission and promised to talk to families he felt would be receptive; he soon reported back that there were a number of households standing by to help. Meanwhile, additional people were joining the cause in Amsterdam, including Joop Woortman, a former waiter and owner of a taxi business, who was known and trusted by many people within the Jewish sections of Amsterdam.

Soon the NV was funneling a steady stream of Jewish children from Amsterdam to Limburg to be placed by Rev. Pontier into Christian homes. Though most of his contacts were Protestant, Catholics predominate in the south, and he soon began approaching Catholic families to meet the increasing demand for safe addresses. Many Catholics opened their hearts and homes, and members of both branches of Christianity pulled together to help save lives.

....

Mieke Vermeer, in her direct yet soft-spoken way, could be the Dutch counterpart of the wandering monk in the

Autobiography of a Yogi

who describes himself as having “long exercised an honest introspection, the exquisitely painful approach to wisdom.” After asserting that true self-examination leads to the perception of “a unity in all human minds—the stalwart kinship of selfish motive,” the saddhu adds, “an aghast humility follows this leveling discovery,” one that “ripens into compassion.”

In Mieke, that compassion has fully matured, but that doesn’t mean she has mellowed. She does not flinch from looking at the world as it is, nor does she hesitate to turn the searchlight of impartial analysis onto herself. Though she can seem pessimistic about what she sees, she is clearly more interested in healing the world than in despairing of it.

....

“I’m willing to talk to you, but first may I ask

you

a question?”

“Sure.”

“You don’t mind if I’m very blunt?”

“No, go ahead.”

“What gives you the right to do this?”

“To interview you?”

“Me and the others. To collect our memories. To look into our lives.”

“I

don’t

have the right, unless you give me the right. Your stories belong to you—it’s just that if you don’t tell me, I’ll never know. Not firsthand.”

“You came all this way to hear firsthand?”

“I wrote you that my father and his family made it out of Poland by the skin of their teeth. Nearly all the relatives left behind were killed. I guess I want there to have been a different ending to the Holocaust—a happier ending. That, of course, is impossible, but if I can meet someone like you, if I can look into your eyes and listen to your stories, then I know that, yes, there was some goodness, there was some decency. Otherwise, it’s just too depressing.”

“Where do you think God was during the Holocaust?”

“I think He was in people like you.”

“If that’s true, then God became very small. Very small indeed.”

I asked, “Where do

you

think God was?”

“I think He was weeping because of all the terrible things people were doing to each other.”

At the start of the Nazi occupation, I was a young teenager living here in the south with my family—one of seven girls in a family of eleven. One day, a young man named Gerard Musch came to our door, wanting to know if we would consider taking in Jewish children.

It was my mother who first made the decision to help. I don’t know what she was feeling, but if she was afraid, she didn’t show it. She said to Gerard, “It’s fine with me. When my husband gets home, I’ll talk with him about it.” She believed she had a duty to care for not only her own children, but other people’s children, too, if they were in danger. When my father came home, he said it was all right. Soon our homestead

became one of the main safe addresses in Limburg. We took in as many as fifteen Jewish children at a time, many of them having been smuggled out of the Creche in Amsterdam. When you added the eleven of us, that made twenty-six in all. Gerard would come every couple of weeks with food coupons, money, clothes, and other supplies. We didn’t have time to think about the risk—it was like we were running a summer camp.

I have happy memories of those days. We had never known anyone Jewish before, but we liked the new children very much, and they quickly became like part of the family. They were free to run around outside, and, because of our location in the south, we didn’t have the food shortage. We had fun together playing and singing. My mother sang also, and if you were feeling down, she would sing you a happy song to cheer you up.

Meanwhile, what was happening in Amsterdam was very exciting. Joop Woortman, who by that time was in charge there, made contact with Walter Suskind, and together they came up with all kinds of ways of getting Jewish children out of the Creche. Lisette Lamon, who worked at the Creche, told us that they smuggled children out in laundry bags, rucksacks, crates, bread baskets, burlap bags, or held under a coat. One newborn even passed through a cordon of SS men in a cake box!

Just before the Creche was shut down in September ’43, there was a tremendous push to get as many children out of there as possible. Jaap, Gerard, and Dick went to the Creche themselves, and, in a daring operation, left with fourteen children. When Gerard arrived to drop some of them off at our house, I begged him to let me join the group. Though I was only sixteen, he saw that there was no stopping me. When I turned seventeen, I took over his route, delivering whatever was needed to about fifty families who were hiding Jewish children. I bicycled all over the countryside, visiting the foster parents and checking up on the children.

Jewish girls playing at the Vermeer homestead with Mieke’s younger sister (far right). Courtesy of the collection of

the Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam.