The Heart Has Reasons (25 page)

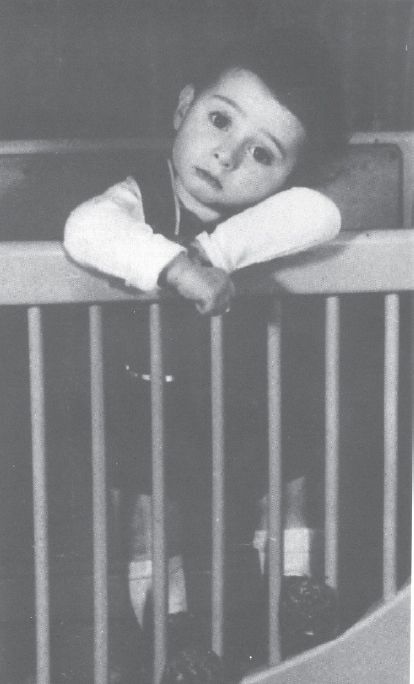

Remy, a young Jewish boy who was detained in the Creche.

Courtesy of the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation,

Remy van Duinwijck: Vrij Nederland (01-18-1986) page 5.

Both the Schouwburg and the Creche were supervised by a committee of three men who worked for the Jewish Council: Walter Suskind, Felix Halver-stad, and Bert de Vries Robles. Those were three really good men. The first time I spoke with Water Suskind, he said, “The reason we’re sitting here is to try to sabotage the Germans as much as possible—to use the power they have given us to free as many adults and children as we can.” Now that was the right idea! He himself had come from Germany in ’38. All three of those guys were Jewish. So we put our heads together to coordinate how to save those children.

The trouble was that the Germans were very well organized. They had a list of everyone who came in, and everyone who went out. If they found out that even one child was missing, the whole thing would have been over. So it was a two-step process: get the child out, and cover your tracks. And that’s where Felix came in. Felix developed a system to doctor the books so that there was absolutely no record that the child had even

been there. He became an expert at that. But Walter Suskind was really the heart and soul of the operation. You see, there was a Gestapo officer named Aus der Fünten that Walter had known in Germany—they had gone to school together. Aus der Fünten was now the man in charge of carrying out the deportations in the Netherlands, and he was around the theater all the time.

So what did Walter do? He became his drinking buddy. Walter was an actor; he could pull off something like that. In Germany, he used to perform at the theater in Cologne, but it was with Aus der Fünten that he gave his greatest performances. He and Aus der Fünten would go out drinking, and that was how Walter kept him away from the theater and the Creche. And it worked incredibly well. The Germans didn’t find out what was going on because the big boss was too busy toasting Walter! And in the meantime, Walter was organizing, planning, talking to all kinds of Resistance people, and talking to us. He would say, “Well, I have this many children of such and such ages. Can you place them?”

So once he and his people got the children out of the Creche, we would take them either north or south. We would talk to our contacts and ask, “Have you got a place for a girl of six, or for a boy of fourteen?” A girl of six would be no problem, but a Jewish-looking boy of fourteen: that would be more difficult. If we talked on the phone, we’d use code: “I have a package of ersatz coffee” would mean, “I have a dark-haired Jewish boy.” We’d need to send him down to Limburg where the people are darker. “A tin of ersatz tea” would mean a Jewish girl who could pass in Friesland, one with lighter features. So we were always in close touch with our contacts in both the north and south. We’d say, “Well, how is it, can you manage it, can you find us something?” And then if it worked out, we’d go back to Walter Suskind and say, “Yes, we can do it.” Then he and the girls working at the Creche had all kinds of ways of smuggling them out. Once they were outside, several of the girls from our group would be waiting to take them to the safe addresses.

To get to Friesland, they’d have to go on a ferry from Hoorn to Staveren. And there were always lots of German soldiers on that ferry, and the girls would sit with the children, and talk to the soldiers. Those soldiers had

no idea

they were Jewish children. I mean, the Gestapo would have known, the SS would have known, but not those German recruits. And the girls let them play with the children, because nothing looked better than that.

You know, sometimes it was safest to do things right under the noses

of the Nazis. When the house I lived in on Keizersgracht was raided in September ’42, I had to escape through the window and run across the roof to keep from being caught. Wouter and I then dived under in the sorority house on Utrechtsestraat where my girlfriend Hansje lived. Two roosters in the henhouse! But the beauty of it was that we were right across the street from the Gestapo headquarters. We could see all their comings and goings, but they never suspected we were there.

So once the girls arrived at the safe addresses, they would meet the foster families and drop off the children. Some of the children looked very fetching; others were sickly and pale. My cousin Mia Coelingh, who used to accompany Jewish children to safe addresses, tells a wonderful story of the time she dropped off one very beautiful little girl, and all the neighbors came over to admire her. One of them decided on the spot that she would take a child also, so on the next trip Mia brought her a skinny child who looked really pathetic. The woman said, “But I ordered a beautiful child like the other one!” Mia replied, “You don’t order anything here! You’re supposed to be saving a human being. And this one just had chicken pox!” The woman went ahead and took her, and it all worked out fine.

In general, we didn’t follow up much with the children, except to deliver food coupons and supplies. We figured that if the parents dared to take in a Jewish child, they should be able to do it their own way. But if something was wrong, I would hear about it.

Once we placed a fifteen-year old girl with a family, and she told us that the foster father was wanting to have sex with her. We found another place for her immediately, and—guess what?—the exact same thing happened. So I placed her with two old ladies, and that solved the problem.

As for our daily life as rescuers, we never knew what each new day would bring. Wouter and I would talk with the girls in the morning, and we would figure out who would do what. Information was coming in all the time about children who needed to be hidden and addresses that were available. And through it all, we worked closely with Walter Suskind, who was coordinating not only with us, but with others groups as well, and not only helping with the children, but also smuggling many, many, adults out of the theater also.

As the war went on, Wouter and I really began feeling the weight of the responsibility we had taken on. Many children were depending upon us, and we had to be extremely careful. It was frightening. I mean, you realized that if you were caught it could be the end of you. No one is a hero

when he’s being tortured; you never know how long you’ll be able to last. But we couldn’t think about that. Sometimes at night I’d wake up in a cold sweat. But during the day there was so much work to do that and you just threw yourself into it.

The biggest precaution we took was to make sure that no one saw more than one piece of the puzzle. We told the girls as little as possible because the less you knew, the less you could give away. Wouter and I tried not to write things down, although we had to keep a list of the children and where they were. If there had been one master list and it got into the wrong hands, the consequences would have been disastrous. So we broke the list into three parts, and kept each part in a different location. Only if the three parts were put together could you find the children, and even then it was in a kind of code.

We had a rule that if you were caught, you needed only to keep your mouth shut for twenty-four hours. After that time, we would have moved everyone you knew in the group to new addresses and gotten them new names, along with new false identification papers. Another thing: we never let the parents know the address where their children were being hidden. Can you imagine if the parents decided one day that they had to see their child? No, we never gave out the addresses of the children to the parents, or to anyone else.

Once I got a letter from Westerbork from the parents of one of the children we had hidden—it didn’t come directly to me, of course, but to my contact address—and they wanted me to bring their daughter to them in Westerbork. That, of course, was out of the question: If I went to Westerbork with a Jewish child, I’d immediately get arrested. But still, I thought a lot about that letter, and I realized that even if I could have been invisible, I wouldn’t have done it because it would have endangered the child.

The parents had given us their children to save, so now we had to do our job and save them. We didn’t realize at the time what an unbelievable thing it was that these parents had been forced by such extreme circumstances to give their children away to young people who were themselves barely adults. I think that one of the reasons we were able to do the work was because we were not yet parents—we couldn’t fully understand what it was like for them. But, despite that blind spot on our part, I must say that once those parents turned their children over to us, we assumed responsibility for those children, and we took that responsibility very seriously.

For instance, the LO wanted to give us food coupons for the chil

dren in hiding, but they insisted on knowing their addresses. I said, “If that’s what you require, we don’t want your food coupons.” Instead we got food coupons from one of our contacts in Friesland. They were doing all kinds of things up there, like stealing coupons from the city hall. So we had no problem getting food coupons, and we never had to give out any of our addresses. I think this was one of the reasons why not a single one of our children or rescue workers was ever caught, although we had some close calls. It’s always 80 percent luck that you survived, isn’t it?

Krijn van den Helm, one of the leaders of the Dutch Resistance

My near brush with death occurred when I had to rendezvous with Krijn van den Helm in August 1944. Krijn was the head of the Resistance in Friesland, a wonderful man, and absolutely a very dear friend. But towards the end of the war, someone had talked in Friesland, and all the Resistance people in the north were on the run. Krijn called me from a pay phone and told me he had left Friesland and was hiding in Amersfoort, a city in the middle of the country. He said he needed to see me. So I met him in Amersfoort and he said, “I need a new false ID. But it must be a real one, not a copy. Can you do it?” I said, “Give me your photo, and I’ll take care of it. I’ll have it for you in a week.” The real IDs were the ones that were stolen from the municipal offices. I had contact with some people who could do that, so I went to them and I got him a real ID with his photo attached.

A week later I was to meet him at six o’clock in the evening at a certain address. He might have been the man the Germans were most after in the entire country, so I had to be careful. I said to my wife, Hansje, “I have the feeling I mustn’t go alone.” Why? Because this was a very important mission, and I couldn’t afford to get stopped on the way. I still had my papers that said

I was a train inspector, but on that day I didn’t trust them for some reason—I had the feeling that something might go wrong. Since riding on the train was not a danger for a woman, I said to Hansje, “Darling, please come with me. It’s too important—we must go together. You carry Krijn’s ID. Even if they pick me up, they won’t search you.”

So she came with me, but when we got to the station the strap of her shoe broke and it slowed us down. We missed the train by a few seconds, and I got very angry. I prowled around the station for a few minutes, and then sat down with her and waited. After a long hour, we caught the next train, but when I finally reached Krijn’s address, a woman hissed at me, “Beat it!” so I left immediately.

Later I learned what had happened. That afternoon, some men from the SD had tracked Krijn down and surrounded the house. They wanted to get some information out of him before they arrested him, so they had an operative in plain clothes knock on the door who pretended to have a message from Esmée van Eeghen—a woman Krijn worked very closely with in the Resistance. Krijn came down, but he knew right away that something was wrong. Looking out the window, he saw that he was trapped. He reached for his pistol, but the other man shot him instantly. The SD later punished that man for they had wanted to get Krijn alive.

Whenever the SD arrested someone at a house, they would remain for twenty-four hours to catch anyone else who might show up. In this case, perhaps because Krijn had been killed and needed to be removed, they only stayed until 6 P.M.—the exact time of my meeting with him. If the strap of Hansje’s shoe hadn’t broken, I wouldn’t be sitting here. That’s the kind of luck you need. But you must listen to your intuition. Your intuition is what will save you.