The Heart Has Reasons (18 page)

But while this was going on, shots rang out, and I heard bullets whiz right over my head. Some drunken German officers were firing into the crowd! People screamed and ran for cover, but some of them were struck down. Suddenly our festivities had turned into tragedy. Now, each year, people gather on the Dam to observe a moment of silence in remembrance of the nineteen people who were gunned down there that day, and everyone else who died during the war.

On May 8, Winston Churchill came on the radio and declared V-E Day—Victory in Europe Day. The occupation had lasted almost exactly five years. And the Third Reich that the Germans imagined would rule for a thousand years had been destroyed—or destroyed itself—in barely more than ten.

In the weeks and months that followed, my husband returned, but my younger brother was never seen again. I thought that the Blochs would come right away for Nettie, but I didn’t hear anything from them.

I remember someone asking my age. I said, “Twenty-one,” but then I corrected myself and said, “No, twenty-six.” It was as if time had stopped during the war. Nettie was now five-and-a-half; I had loved her as my own child for over three years. But then her parents took her back.

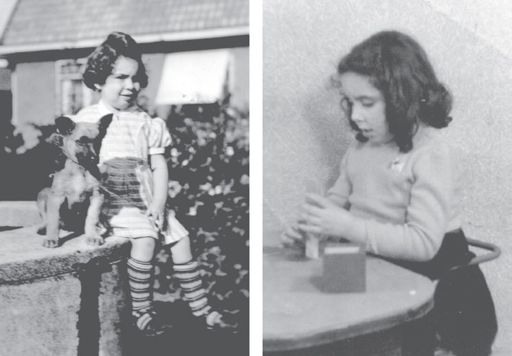

Two photographs of Nettie taken after the war, the only photos that Clara has in her scrapbook of Nettie as a child.

Not such a nice story. Suddenly, one day they appeared and wanted her. Nettie was frightened and didn’t want to go with them, because she didn’t remember them. She was crying, and saying to me, “Mamma, don’t you love me?” I said to Sylvia, “She must make the change slowly. Otherwise it won’t be good.” But they wanted Nettie back right away. She said, “It’s my child, and I want her back.” I had become very attached to Nettie, so it was like having my own child ripped away from me. But what could I say? She was the mother, so I gave her back.

As I predicted, it didn’t turn out so good. At school, they thought there was something wrong with Nettie; she wasn’t able to follow her lessons. When you have a child, you must talk to the child, but the mother was coming to me to talk about the child. I told her, “Nettie is not dumb—she is just disturbed because of the change.” And every night I went to bed crying for Nettie. For four weeks I stayed in bed at my parents’ house crying. I couldn’t eat; I could only cry. And Sylvia wasn’t even friendly to me.

But over time Nettie came to think of herself as having two mothers, Mamma Sylvia and Mamma Clara, and she remained connected to both of us. All my life I have loved children, wherever they are in the world. Now I have five children and eight grandchildren, plus Nettie, who will always hold a special place in my heart as my first child.

What was your life like after the war?

My husband had been through a lot at the hands of the Germans and was lucky to have survived. We wanted to start a family, but I couldn’t get pregnant. I went to specialists, but it did no good. Then, when I turned thirty, just for a thrill, I went parachute jumping. Suddenly, I was pregnant! Soon I had my first baby, a girl. A year later, I had a second girl. And then, after that, three boys.

But my husband had started to drink. After work, he would go straight to the bar and wouldn’t come home until morning. I stayed with him over the years, but he drank away our earnings so I had to go out at night and work. For fifteen years I worked the night shift at a nursing home, but I started getting excruciating migraines. Finally, we divorced, and after that things were much better.

Nettie grew up and moved to Israel. Later she married an Orthodox

Jewish man, and now they have two children. They call me Oma Clara.

Clara Dijkstra as an elder.

I have taken twelve trips to Israel to visit Nettie, and she has often come here to see me. The first time I went there, Nettie’s rabbi came over and hugged my neck. He said, “Whoever saves one life, saves a whole world.” I started to cry.

After Nettie had her first baby, she called from Israel to say she was going to come to visit me, and the Blochs. But the day before she was to arrive, Sylvia Bloch called and said, “Nettie won’t be coming. You do not keep kosher and her new husband is very strict about the Jewish dietary laws.” I cried and cried.

The next day Nettie called to say they were on their way over! She arrived with her husband, and I had plenty of time to hold the new baby. They stayed for hours, but when it came time to make dinner, I didn’t know what to do. Would he eat my cooking? But he said, “Mrs. Dijkstra, if it wasn’t for you, I wouldn’t have my wife. I’ll gladly eat whatever you put before me.” He would have eaten an ox if I cooked it for him!

He spoke truly: if not for you, Nettie would most likely have been killed. Why did you

help?

It was only human.

In the years since the war, have you ever again had the occasion to help children other

than your own?

I have a girl in Sri Lanka, through an organization called Foster Parents. I’ll show you her picture. I send forty-five guilders a month to pay for her food and the living expenses. I like to write her letters, and they translate them into Sinhala. And she sends me back little paintings, and I get

reports about how she is doing.

Some time ago, I took in a boy through a program that gives disadvantaged children a vacation. I signed up by phone to keep him for a month. When I went to pick the child up, the man led me over to a large boy with a watch and a calculator. My goodness, he’s German, I thought. Then I thought, well, maybe I’ll be glad it turned out like this; I might even grow to love the child.

It didn’t work out so well. All he wanted to eat was fast food with Coca-Cola. When I took him on a vacation to the beach, he spent the whole time buying things. I called the agency. The woman said, “You have to understand, some of these children are not physically deprived, but they are in emotional pain.” Yah. Then one day I noticed that all the money was missing from my drawer—about 150 guilders. He said, “Well, I want to buy a very expensive bike.” I called the agency again, and they said they would come to get him the next morning. I realized that all the things he had been buying in Zandvoort had been with my money. When they came to pick him up, my grandson said, “Why don’t you search him?” I said, “No.” There are so many things in life you just have to put behind you. It was a bad experience, that’s all.

Do you feel it’s more difficult now for children to grow up in a wholesome way

than when you were a child?

When I was fourteen, I used to help take care of the children at the local school. At the end of the school day, I would say to them, “Come on over to my house—you can play there.” Now, you can’t do that. You have children coming to school with knives, guns—it’s meshugah, it’s crazy. The children see movies with drugs and violence, and they get the idea that this is exciting. I can cry all day after watching one of those movies. The police pick up young people who use drugs, but the big dealers stay out of range. When they do pick one up, they’re afraid to do anything because of his connections with drug cartels. Oy Gevalt! What’s the world coming to?

Then, there is that terrible fighting going on in Africa. Brother attacks brother. I can’t understand it. Who cares about what is good for the people? The soldiers go and fight, but it’s all about what’s in the land—oil or uranium. It costs so much money, and all the while the children have nothing to eat. Whenever there’s a war, it’s always the children who have to suffer.

I believe that most of the wars are all about money, money, money.

Switzerland is a nice country, but the Swiss were not nice during the war—not nice. They wanted the valuables of the Jewish people, and they laundered money for the Nazis, money the Nazis had stolen from the Jews. There were many war criminals who had so much money that they could pay off the right people, and live without worry in the Vatican until they could catch a boat to South America. This is how men like Josef Mengele and Adolf Eichmann were able to escape to Argentina or Brazil.

The schools teach the young people about history and current events, but many of them say, “What do I care?” They’re more interested in watching TV, and sometimes the parents let them watch anything they want—not good. Many families now eat dinner while sitting in front of the TV set—also not good. With so many mothers and fathers working, the children get out from school and come home to an empty house. Then the parents wonder why their children won’t talk to them. As a child, when I came home from school, my mother would be there waiting for us. She had some hot tea and honey wafers set out on the table. With the children today, no one is there for them. Then they become angry and get into trouble.

But where is the love for the children? No, you’re working for another car, a better house. . . . You can have your cars and your luxurious homes, or you can have a close, loving relationship with your children. But you can’t have it both ways. If children get the love and attention they need, they will have a chance to grow into good people. It’s so important. When I look at Nettie, I see that the love that I gave her, she is now giving back to her own children.

It was Nettie who nominated you for the Yad Vashem award?

She gave me some forms to fill out, and told me it might take some time, for they have to check everything and find witnesses. In fact, many years went by and I forgot all about it. Then suddenly, they gave me a medal in my old age. I was surprised!

How do you feel about the way society treats its elders, now that you’re almost eighty?

It used to be that the mayor of the town would come to see you on your hundredth birthday, but now becoming a hundred years old is not so unusual. I could live that long; but then again, I might die tomorrow.

When I die, I want to be buried, not burned. Just put me in the ground with the worms. And no fancy funeral—all I want is one red rose and one white rose from each of the children. Human values, not material things. That’s what makes me the happiest.

On Christmas, all my children come over with their families for dinner, and I have to set up this table, and one there, and then a whole table over there. Three tables I have to put up to seat all of them. And the food—I make it all myself. When my children and grandchildren come together like that, sometimes I just ache with love.