The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (33 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

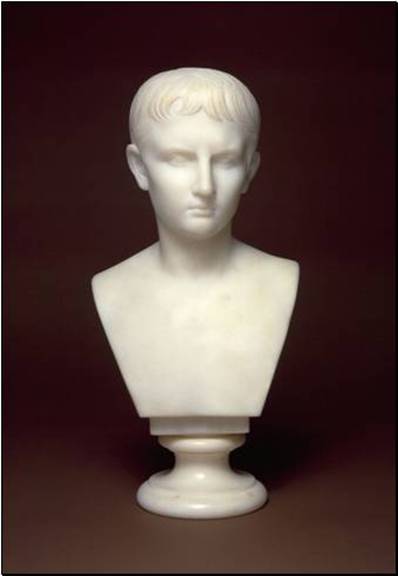

Figure 36.

Young Octavian,

ca. 1873

Edmonia’s stylish rendition above of the antique

Young Octavian

was one of many. Photo courtesy: Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Norman Robbins

When customers failed to pay, Edmonia now threatened to sue – no pleas, no begging, no crude shelf of shame marked

‘DELINQUENT’

à la Powers. She had learned a valuable if somewhat harsh lesson from the late Hugh Cholmeley.

Before Edmonia departed for Rome in 1865, Dioclesian Lewis had promised $100 extra if she should do his portrait justice.

[491]

When it arrived in Boston two years later, the

Transcript,

the

Commonwealth,

and the

Christian Recorder

had showered the marble rendering with praise. His brother had taken a plaster copy. Someone ordered a second marble (Figure 19). This, the first commission she had delivered from Rome, was even shown in New York. She later smirked to a reporter, “He refused to pay this, but my friends there made him do it.”

[492]

When another stingy patron refused final payment on a memorial commissioned for Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge MA, she threatened to sue. Rather than appear in court, the family paid. Writing in Boston to her sister, Anne Whitney wondered whether the family would actually install the monument.

[493]

Gossip had already doomed the plan. The family marked the plot with a slab of beautiful green slate, and the incident was nearly forgotten.

In 1879, a former slave living in the former Confederacy forced Edmonia to reach across national frontiers and the Atlantic Ocean. This time all else failed and she did go to court, setting experts against experts in full public view. Both sides endured public jeers. Sensation-seeking editors in St. Louis, MO, feasted on the celebrity event to the delight of newspapers around the nation.

[494]

At issue was a debt of $500 outstanding on a memorial ordered for a grave in Calvary Cemetery, the last resting place of St. Louis’s most prominent Catholics.

[495]

Edmonia’s commission meant to mark the burial site of Madame Pelagie Rutgers

.

[496]

Madame Rutgers was a Haitian descendant and former slave who had married the colored son of a rich Dutch merchant. She was an important landlord and a member of the colored elite of St. Louis. Her wealth was estimated at $400,000. According to one legend, she gave her only daughter diamond earrings costing $10,000 and a veil costing $900 when she married. The daughter actually wed

after

her mother’s passing because Madame Rutgers objected to her match with a former slave. The wedding, nonetheless, was well attended and locally renowned.

Answering the suit were daughter Antoinette and her husband, James Peck Thomas. He was a successful barber who also ran his wife’s real estate. James had toured Europe in the summer of 1873.

[497]

Traveling south from England, he eventually met the rector of the American College

[498]

in Rome and learned of the colored sculptor. Excited, he soon found he had missed her. She had sailed from Le Havre just as he embarked at New York.

Edmonia must have been wise enough to leave forwarding addresses. James sent word, it seems, asking her to visit him in St. Louis. In America, Edmonia revised her plans, venturing into the former slave state.

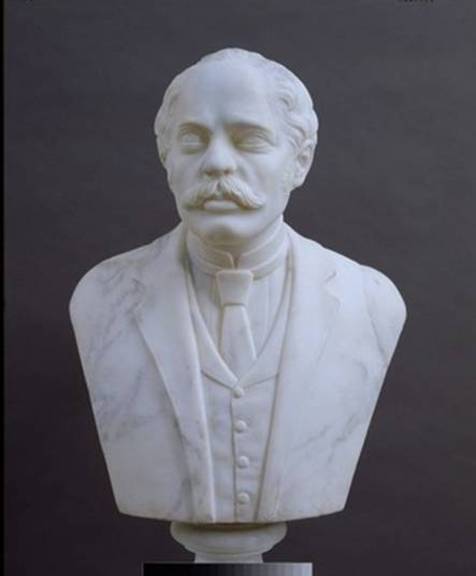

Thus, James sat for a marble bust that she produced after her return to Rome. Dated 1874, it reveals a well-dressed gent with a pleasingly round face, wavy hair, and a generous, waxed mustache (Figure 37).

[499]

Historians Franklin and Schweninger used the bust to point out his resemblance to Justice John Catron, who voted with the majority in the infamous Dred Scott decision – and who was his father.

Mrs. Thomas had sought a memorial for her mother’s grave. Edmonia’s Catholic art, respected name, and shared heritage must have seemed perfect. From a clay model made at their home, the Thomases ordered a marble statue of the Virgin Mary at the cross with a base and pedestal.

[500]

No one expected a turf war at the cemetery. Monument vendors in St. Louis must have raged at such a windfall going to this colored invader of their turf. From the tone of the news coverage, it seems the trouble sprung from the notion that rich colored people were ignorant fools just waiting to be fleeced. The Thomases were undoubtedly sensitive to such slanders. They overreacted and refused to pay Edmonia’s balance due on delivery.

Racist newspapers mocked the legal proceedings, joking that Mrs. Thomas found “[a] particular defect … in one of the wings. It lacked the graceful contour, the aerial taper of the pen [pin] feathers so essential to a successful flight through the regions of space at the witching hour of midnight…. Mrs. Thomas refused to receive the angelic visitor, and it was left at a marble-yard, where, like the wandering peri, it still waits for the gates of Bellefontaine to open.”

[501]

In court, a monument worker fumed, explaining his refusal to cooperate: “The reason [the memorial] was not put up was because he did not know how to put it up, and he had been in the business forty years; he could not put this one up, but if they could get anyone that could do it they had better get him.”

[502]

Other witnesses opened a second front – questioning the statue’s value as an original work of art – calling it “a burlesque.”

Edmonia’s attorneys entered her sworn statement in which she claimed the work met with the daughter’s enthusiastic approval and that she executed it as agreed.

[503]

A further statement by an Italian sculptor and testimony of local artists backed her up.

Edmonia won the suit, but the trial court awarded her only one dollar.

Her lawyers appealed. The higher court likely saw danger in setting a precedent that would apply to all. It held, “where an artist has been employed to execute from design at a stipulated price the party employing cannot refuse to pay because the work does not suit the taste of manufacturers or importers of tomb-stones or because it is not the buyer’s own taste, or because he finds he can buy figures in the marble-yards of a large size at one-tenth of the cost of a work of art which he has ordered.”

[504]

The ruling must have stung for a long time. In Boston, the

Transcript’s

summary bore the tone of a studied sneer.

[505]

Black History tours in St. Louis will find no Virgin Mary at the gravesite of the fabulous Pelagie Rutgers.

[506]

Figure 37.

James Peck Thomas,

1874

On tour in Europe, James Thomas discovered there was a colored sculptor in Rome – but she had gone to visit America. In time, he sat for this bust, which she carved the next year. Photo courtesy: Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College.

The New York Times

Edmonia had her eye on San Francisco ever since her brother headed there in 1852. He banked there, even after settling in Bozeman, Montana Territory. He likely encouraged her to head west as he had done when they met in 1870.

[507]

Making a sculptor’s excursion practical, a golden spike had joined east and west coasts by rail the year before.

Touring America each year, something other expat sculptors rarely did, she had an advantage in spite of the mean traps awaiting a colored traveler. She could investigate deliberately, study timetables, discuss accommodations, and make plans. She decided to be the first woman sculptor to show on the west coast. The trip was a new adventure, never to go out of style. Assured of a hotel and a showroom, she carefully selected what marbles she thought she could ship and sell. By most accounts, she left her affordable plaster figures behind.

By mid-spring of 1873, her plans for the Centennial must have advanced enough for her to focus on this digression.

Forever Free

had gained from a travel hiatus. She would let her

Cleopatra

cure while she made her longest sortie ever.

Before she left, a New York book publisher turned up at her studio. Awash with inherited wealth and position, he frothed in bubbles of self-satisfaction. Seeing

Hagar,

he recognized Edmonia’s exceptional enterprise and ambition. He opined to his diary, however, it would take generations for members of her race to compete with whites in fine art. Ignorant of, or refusing to accept, the Italian judging that gave her high prizes a year earlier or the commission from the urbane Union League Club, he termed her

putti

“laughable.”

[508]

The uncredited writer from the

New York Times

was no more generous. After visiting the sunny, flat Via Margutta to see Harriet Hosmer and Randolph Rogers, he hiked up the Quirinal Hill to visit the illustrious Mr. Story. Edmonia’s shop stood nearby. His report contrasted “the grandeur of [Story’s] museum of great works with the modesty of a studio which lies not far from it ... a humble looking house, where a glass door permits you to see a couple of workmen busily chipping away at blocks of white marble.”

[509]

Recognizing

Longfellow

and multiple sizes of the

Hiawatha

series, he mentioned

Awake

and

Asleep

without noting her gold medal. She surely mentioned it, but he conceded only, “there are traces of genius in these sculptures, you cannot doubt, yet the execution seems so imperfect, and the expression of the fancy busts is so peculiar that you feel you are in the presence of art, but of art in the early beginnings.”

Edmonia told him no stories of wild Indians and the “stone man.” Instead, she griped about expenses. He wrote, “This little low woman [confided] that today is pay-day, and pay-day is always an unpleasant time when [she] is troubled by many cares.” He explained her marketing tactics in terms of class: “the small statues and heads are for people with slender purses, ‘for you know we must sell our work if we want to live.’”

His shallowness becomes more apparent as he gushed over her celebrity subjects, “touching deeply your heart as she speaks of Horace Greeley and Charlotte Cushman, and the goodness they have shown her ... makes her eyes brim over.” (Greeley had recently died; Cushman, battling breast cancer, had left Rome, never to return.) The account ended, “wishing the poor child of a suffering race Godspeed [and] liberal encouragement so as to cultivate her talent and do honor to her genius.”

Didn’t Edmonia mention her titled patrons and her commission from New York’s Union League? Like her prizes, no such details appeared in the article. They could have seemed impossible for this “little low woman.” Or perhaps the thought of showing real respect made the writer uneasy. It did not matter. However soaked with superiority about the “poor child” and nonsensical comments about art and genius, the article would validate her for readers in America.