The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (29 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

Nor did the

Art-Journal

reveal her plan to take

Hagar

to Chicago. The potential for sabotage could have stirred worries rooted in the tricks and traps of Oberlin’s boarding house intrigue. Vinnie Ream held all Rome’s attention, anyway. As the tide of foreigners receded before the heat of summer, Edmonia quietly headed westward with

Hagar

and a number of other works.

When she was found three months later by a census taker in New York City, the petite artist claimed $20,000 worth of personal property. That alone was unusual for the building at 193 Prince Street (corner of Sullivan), which catered to colored professionals, as well as for the block.

[432]

Hagar

was probably still in its crate, but a pale crowd of marble commissions and reddened plaster busts could have populated her room. Describing her as a twenty-four-year-old female mulatto sculptress, the canvasser was confounded enough to misspell her first name as “Edmond.”

[433]

Rev. Garnet and the Shiloh church shared the neighborhood.

By August, she was in Chicago.

The imposing, side-whiskered John Jones and his wife Mary were there. He was the first colored pol to rise in the Midwest after the Civil War. After campaigning with Frederick Douglass against the harsh black laws of Illinois, he organized their repeal. He fought to open schools to colored children. He advanced rights to vote, to serve on juries, and to testify in court. Unlike most colored leaders, who were ministers or lawyers, he ran the largest tailoring and dry cleaning firm in the growing city of 300,000. By 1860, he had achieved enviable wealth. He discussed civil rights in economic terms. Businesses lost money, he said, by not being able to call colored witnesses when their wagons crashed or their goods went missing. Extending rights to everyone meant money in owners’ pockets.

We believe, based on sparse evidence noted here, that John and Mary Jones welcomed Edmonia to Chicago and guided her. Well-known for hospitality, they had hosted John Brown, Frederick Douglass, and other reformers at their palatial home.

In Chicago, Edmonia became the first colored artist to openly confront racial supremacy outside the New England haunts of radical Reconstruction. Having learned a harsh lesson in Boston, she plied the press in advance and appeared with her work. It is likely she produced her undated eight-page leaflet titled

How Edmonia Lewis Became an Artist

[434]

as she planned her most ambitious venture to date. Such flyers had benefited Powers’

Greek Slave,

Brackett’s

Shipwrecked Mother,

and other popular works of art.

Notably, hers called her “Indian girl” as had Tuckerman’s critic and others who had met her. It recited a born-in-a-wigwam tale and described her “wild, roving” life. It then couched her latest work in terms extravagant enough to suggest the golden pen of some particularly articulate fan. Whoever wrote it understood publicity and enough of a sculptor’s process to write: “Her beautiful statue of Hagar is the result of patience, of hope, of a thousand delicate touchings and retouchings. God’s gift to Edmonia Lewis is unconquerable energy, as well as genius; and these two combined enable her to

rise

above all

prejudices of race

or

color,

and command the respect and honor of all true lovers of art.”

The leaflet spread the word like a modern press kit. It made interviews easier by laying out her history. It also sprayed a comet’s trail of squibs, blurbs, items, facts, and fillers to be caught by some writers and reprinted by others. Carefully filed away by the nation’s newsmen, it kept her name in play and dominated biographical sketches into the next century. No one seemed to care that it made little mention of the African race referenced by her latest showpiece,

Hagar in the Wilderness.

For the first time in print, the leaflet proclaimed “Wild Fire” as Edmonia’s Indian name. A simple device, it reflected her aunts’ rustic charade – speaking their native tongue in public and wearing exotic costumes – to seduce prospective buyers and sell their crafts.

[435]

Away from tourists, they spoke English and dressed like anyone else.

Studied more closely in our Epilogue, the “Wild Fire” brand seems to express Edmonia’s bold personality and her desire for attention. Calling forth her inner fury, it gave the world warning. She would not be controlled, predictable, or typical. She would go her own way, burning brightly and demanding respect.

Farwell Hall had been built by the Chicago YMCA in the heart of the business district. Able to seat three thousand, it was Chicago’s most important conference center. It is remembered for its rousing revivals and furious political contests.

Edmonia rented show space. Then she placed ads and visited newsrooms. A week before her display opened, a

Chicago Tribune

feature urged art lovers to see it.

[436]

In follow-up, a columnist cooed how much Edmonia’s “womanly grit, patience, and perseverance can accomplish, in the face of all obstacles.”

[437]

He concluded, “I think her bravery and persistent determination deserve recognition, whatever artistic ability she may possess.” The

New York Times

reprinted the column two weeks later.

Her ad in the

Chicago Tribune

flaunted her race. With slight variations, it ran daily for a month. Other periodicals – from New York’s

Evening Post

and the

Brooklyn Eagle

to the weekly

Janesville Gazette

in rural Wisconsin, and the witty New York

Punchinello

– noted her show. As far away as Germany, a monthly for female lawyers hailed the appearance as eloquent proof of the ability of women and of colored people.

[438]

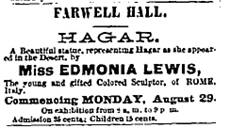

Figure 31. Advertisement,

Chicago Tribune,

1870

This ad was the first in a national newspaper to emphasize the race of an artist.

Lucy Stone’s

Woman’s Journal,

which started that year in Boston, began following Edmonia’s career, posting brief updates within its front page “Concerning Women” feature. It was unusual in that it often did not mention her color.

Edmonia’s future ads also downplayed her race.

[439]

Perhaps in hindsight, she decided it was not helpful or, worse, a form of self-segregation. Editors and writers usually made the point anyway. As a “colored woman sculptor,” she was quite alone – again a social outlier. As a “woman sculptor,” she joined the small group led by Hosmer. As a “sculptor” with no adjective, she joined all sculptors. It was an ambition shared by Hosmer, Whitney, Stebbins, Ream, and others. They used their sex to overcome their disadvantage, but they doggedly fought to show without reservation in art’s main course.

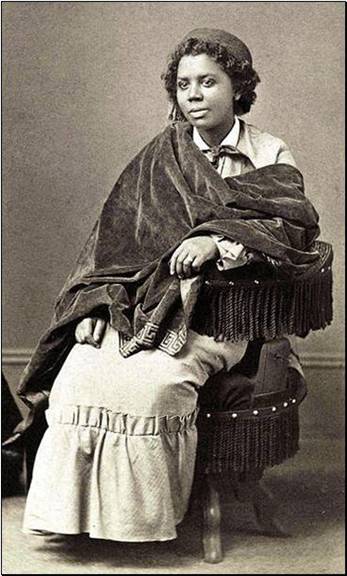

As an artist at war with long-held prejudices, Edmonia’s dark skin and gender became essential parts of her show – one of several lessons learned from Boston. She took time in Chicago to have herself photographed by an outstanding portraitist for a stylish

carte de visite

[440]

(Figure 32 and 47) that she could hand out. The souvenir helped fans recall her and share with friends and family. For many visitors, her skin, her African features, and her poise stimulated more discussion than the still form she had freed from pale stone. The combination was unprecedented and powerful. Thousands of people paid twenty-five cents a head to see for themselves. Many spoke with her. Some were amazed and delighted. Others were incredulous, boorish, and abrasive.

Troublemakers could be expected. Their faces often gave them away, separating them from friendly visitors. As they fumed, she faced them with brave calm, perhaps satisfaction. She had chosen to defy their treasured advantages. Jones and the Chicago YMCA would have been able to keep her safe, but no one could insulate her from the inevitable hate speech, spit, and the occasional mean thump. The effect must have been alternately draining and stimulating. She did not complain for the record after 1869, but witnesses would express outrage on her behalf when she returned to Chicago years later.

[441]

Figure 32.

Edmonia Lewis,

by Henry Rocher, 1870

The gold band on her left ring finger, a traditional symbol of marriage, cannot be traced to any union. It likely served to make her respectable to tourists and as a first defense against unwelcome amorous advances. Henry Rocher, Chicago’s leading portrait photographer of women, printed at least

six poses from this session. Photo courtesy: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Hagar

Although Edmonia’s powerful allegory drew crowds of viewers, it remained unsold. She decided to hold a raffle. Many artists sold their work this way. The tactic brought publicity and fresh traffic – with potential to sell other items. She offered four hundred tickets at $10 each.

[442]

As when raising money for

Longfellow,

she provided a premium to subscribers: a drawing of the statue engraved and printed on high quality paper. If she sold out, she would be $4,000 ahead, not counting her expenses or what she took in at the gate.

Ultimately, a leading Republican from south Chicago won it.

[443]

The Revolution

reported the raffle brought $3,000. Edmonia claimed the show grossed $6,000.

[444]

At twenty-five and fifty cent admissions, thousands of visitors had paid to see her and her work. A year later, the Great Chicago fire destroyed most of the statue.

[445]

In America, Suffragettes Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony had joined the abolitionist coalition in the belief that it served their cause. Following the Civil War, they started a magazine, the

Revolution,

to augment their lectures and other activities. Edmonia’s

Forever Free

had represented a chance to bang home their case. At the risk of repeating, they had written:

Miss Edmonia Lewis, the colored artist, has sent home from Italy a statuette group in marble of two figures illustrating the act of emancipation. It is on exhibition in Tremont street, Boston.

Black! and a woman! and yet gifted with genius. We hope Wendell Phillips will go and see the statuette, and then consider if the black women of the South are not worthy the right of suffrage. When he demands the ballot, as a weapon of protection for the black man alone, he forgets that the women need it more than the men, not to protect themselves against each other, but the whole male sex, black and white.

[446]

The same issue of the magazine signaled an ill omen: a new suffrage association for white women only. Months later, when the Fifteenth Amendment gave the vote to black men but denied it to women of any color, Stanton and Anthony turned fully in this direction. Beyond opposing it ratification, they mocked “Sambo” and denounced the limits of Reconstruction. They even argued the women’s vote would strengthen white supremacy.

The slant drove away many Republican readers and split supporters of women’s suffrage. The magazine sank into a financial quagmire. After two years, it was $10,000 in debt. Yet they had backtracked to join Edmonia’s complaints about a Cleveland hotel and had remarked, “Her color, of course, was her crime, and even that is scarcely perceptible in a crowd of whites.”

[447]

Other women, such as Lucy Stone, publisher of the

Women’s Journal,

spun a more Republican form of feminism. Enter Laura Curtis Bullard, heiress to a patent medicine fortune, a long-time suffragette, and a

Revolution

correspondent. She was also a successful novelist who had edited the monthly

Ladies’ Visitor

and connected well to powerful Republicans. Raising capital through a nonprofit group, she bought the

Revolution

in May 1870 for $1, leaving Miss Anthony to work off the old debt.