The Information (21 page)

Practical problems had to be solved: making wires, insulating them, storing currents, measuring them. A whole realm of engineering had to be invented. Apart from the engineering was a separate problem: the problem of the message itself. This was more a logic puzzle than a technical one. It was a problem of crossing levels, from kinetics to meaning.

What form would the message take? How would the telegraph convert this fluid into words? By virtue of magnetism, the influence propagated across a distance could perform work upon physical objects, such as needles, or iron filings, or even small levers. People had different ideas: the electromagnet might sound an alarum-bell; might govern the motion of wheel-work; might turn a handle, which might carry a pencil (but nineteenth-century engineering was not up to robotic handwriting). Or the current might discharge a cannon. Imagine discharging a cannon by sending a signal from miles away! Would-be inventors naturally looked to previous communications technologies, but the precedents were mostly the wrong sort.

Before there were electric telegraphs, there were just telegraphs:

les télégraphes

, invented and named by Claude Chappe in France during the Revolution.

♦

♦

They were optical; a “telegraph” was a tower for sending signals to other towers in line of sight. The task was to devise a signaling system more efficient and flexible than, say, bonfires. Working with his messaging partner, his brother Ignace, Claude tried out a series of different schemes, evolving over a period of years.

The first was peculiar and ingenious. The Chappe brothers set a pair of pendulum clocks to beat in synchrony, each with its pointer turning around a dial at relatively high speed. They experimented with this in their hometown, Brûlon, about one hundred miles west of Paris. Ignace, the sender, would wait till the pointer reached an agreed number and at that instant signal by ringing a bell or firing a gun or, more often, banging upon a

casserole

. Upon hearing the sound, Claude, stationed a quarter mile away, would read the appropriate number off his own clock. He could convert number to words by looking them up in a prearranged

list. This notion of communication via synchronized clocks reappeared in the twentieth century, in physicists’ thought experiments and in electronic devices, but in 1791 it led nowhere. One drawback was that the two stations had to be linked both by sight and by sound—and if they were, the clocks had little to add. Another was the problem of getting the clocks synchronized in the first place and keeping them synchronized. Ultimately, fast long-distance messaging was what made synchronization possible—not the reverse. The scheme collapsed under the weight of its own cleverness.

Meanwhile the Chappes managed to draw more of their brothers, Pierre and René, into the project, with a corps of municipal officers and royal notaries to bear witness.

♦

The next attempt dispensed with clockwork and sound. The Chappes constructed a large wooden frame with five sliding shutters, to be raised and lowered with pulleys. By using each possible combination, this “telegraph” could transmit an alphabet of thirty-two symbols—2

5

, another binary code, though the details do not survive. Claude was pleading for money from the newly formed Legislative Assembly, so he tried this hopeful message from Brûlon: “

L’Assembleé nationale récompensera les experiences utiles au public

” (“The National Assembly will reward experiments useful to the public”). The eight words took 6 minutes, 20 seconds to transmit, and they failed to come true.

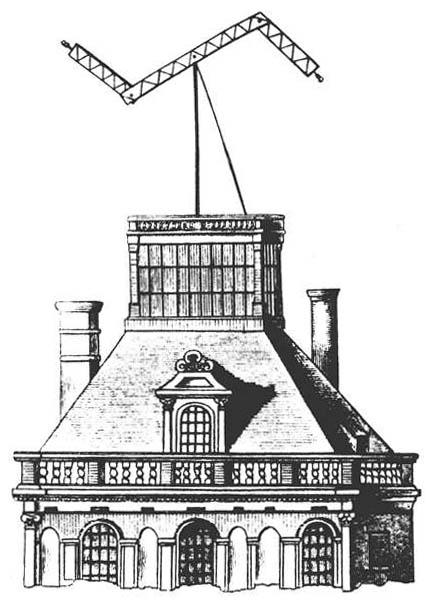

Revolutionary France was both a good and a bad place for modernistic experimentation. When Claude erected a prototype telegraph in the parc Saint-Fargeau, in the northeast of Paris, a suspicious mob burned it to the ground, fearful of secret messaging. Citizen Chappe continued looking for a technology as swift and reliable as that other new device, the guillotine. He designed an apparatus with a great crossbeam supporting two giant arms manipulated by ropes. Like so many early machines, this was somewhat anthropomorphic in form. The arms could take any of seven angles, at 45-degree increments (not eight, because one would leave the arm hidden behind the beam), and the beam, too, could rotate, all under the control of an operator down below, manipulating a system

of cranks and pulleys. To perfect this complex mechanism Chappe enlisted Abraham-Louis Breguet, the well-known watchmaker.

As intricate as the control problem was, the question of devising a suitable code proved even more difficult. From a strictly mechanical point of view, the arms and the beam could take any angle at all—the possibilities were infinite—but for efficient signaling Chappe had to limit the possibilities. The fewer meaningful positions, the less likelihood of confusion. He chose only two for the crossbeam, on top of the seven for each arm, giving a symbol space of 98 possible arrangements (7 × 7 × 2). Rather than just use these for letters and numerals, Chappe set out to devise an elaborate code. Certain signals were reserved for error correction and control: start and stop, acknowledgment, delay, conflict (a tower could not send messages in both directions at once), and failure. Others were used in pairs, pointing the operator to pages and line numbers in special code books with more than eight thousand potential entries: words and syllables as well as proper names of people and places. All this remained a carefully guarded secret. After all, the messages were to be broadcast in the sky, for anyone to see. Chappe took it for granted that the telegraph network of which he dreamed would be a department of the state, government owned and operated. He saw it not as an instrument of knowledge or of riches, but as an instrument of power. “The day will come,” he wrote, “when the Government will be able to achieve the grandest idea we can possibly have of power, by using the telegraph system in order to spread directly, every day, every hour, and simultaneously, its influence over the whole republic.”

♦

With the country at war and authority now residing with the National Convention, Chappe managed to gain the attention of some influential legislators. “Citizen Chappe offers an ingenious method to write in the air, using a small number of symbols, simply formed from straight line segments,”

♦

reported one of them, Gilbert Romme, in 1793. He persuaded the Convention to appropriate six thousand francs for the construction of three telegraph towers in a line north of Paris, seven to

nine miles apart. The Chappe brothers moved rapidly now and by the end of summer arranged a triumphant demonstration for the watching deputies. The deputies liked what they saw: a means of receiving news from the military frontier and transmitting their orders and decrees. They gave Chappe a salary, the use of a government horse, and an official appointment to the post of

ingénieur télégraphe

. He began work on a line of stations 120 miles long, from the Louvre in Paris to Lille, on the northern border. In less than a year he had eighteen in operation, and the first messages arrived from Lille: happily, news of victories over the Prussians and Austrians. The Convention was ecstatic. One deputy named a pantheon of four great human inventions: printing, gunpowder, the compass, and “the language of telegraph signs.”

♦

He was right to focus on the language. In terms of hardware—ropes, levers, and wooden beams—the Chappes had invented nothing new.

A CHAPPE TELEGRAPH

Construction began on stations in branches extending east to Strasbourg, west to Brest, and south to Lyon. When Napoleon Bonaparte seized power in 1799, he ordered a message sent in every direction—“

Paris est tranquille et les bons citoyens sont contents

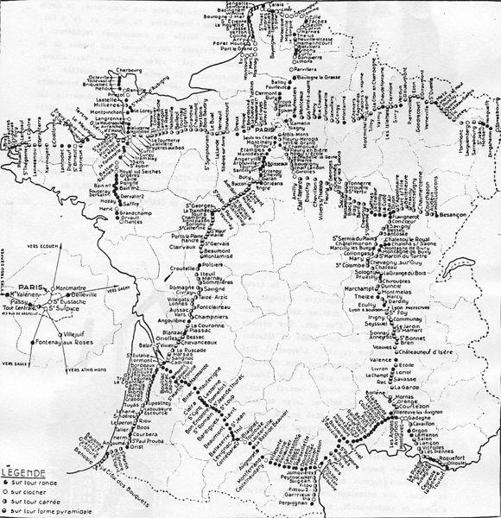

” (“Paris is quiet and the good citizens are happy”)—and soon commissioned a line of new stations all the way to Milan. The telegraph system was setting a new standard for speed of communication, since the only real competition was a rider on horseback. But speed could be measured in two ways: in terms of distance or in terms of symbols and words. Chappe once claimed that a signal could go from Toulon to Paris—a line of 120 stations across 475 miles—in just ten or twelve minutes.

♦

But he could not make that claim for a full message, even a relatively short one. Three signals per minute was the most that could be expected of even the fastest telegraph

operator. The next operator in the chain, watching through a telescope, had to log each signal by hand in a notebook, reproduce it by turning his own cranks and pulleys, and watch to make sure it was received correctly by the next station. The signal chain was vulnerable and delicate: rain, fog, or an inattentive operator would break any message. When success

rates were measured in the 1840s, only two out of three messages were found to arrive within a day during the warm months, and in winter the rate dropped to one in three. Coding and decoding took time, too, but only at the beginning and end of the line. Operators at intermediate stations were meant to relay signals without understanding them. Indeed, many

stationaires

were illiterate.

THE FRENCH TELEGRAPH NETWORK IN ITS HEYDAY

When messages did arrive, they could not always be trusted. Many relay stations meant many chances for error. Children everywhere know this, from playing the messaging game known in Britain as Chinese Whispers, in China as , in Turkey as From Ear to Ear, and in the modern United States simply as Telephone. When his colleagues disregarded the problem of error correction, Ignace Chappe complained, “They have probably never performed experiments with more than two or three stations.”

, in Turkey as From Ear to Ear, and in the modern United States simply as Telephone. When his colleagues disregarded the problem of error correction, Ignace Chappe complained, “They have probably never performed experiments with more than two or three stations.”

♦

Today the old telegraphs are forgotten, but they were a sensation in their time. In London, a Drury Lane entertainer and songwriter named Charles Dibdin put the invention into a 1794 musical show and foresaw a marvelous future:

If you’ll only just promise you’ll none of you laugh,

I’ll be after explaining the French telegraph!

A machine that’s endow’d with such wonderful pow’r,

It writes, reads, and sends news fifty miles in an hour.

…

Oh! the dabblers in lott’ries will grow rich as Jews:

’Stead of flying of pigeons, to bring them the news,

They’ll a telegraph place upon Old Ormond Quay;

Put another ’board ship, in the midst of the sea.

…

Adieu, penny-posts! mails and coaches, adieu;

Your occupation’s gone, ’tis all over wid you:

In your place, telegraphs on our houses we’ll see,

To tell time, conduct lightning, dry shirts, and send news.

♦