The Information (23 page)

Suppose the message to be sent from the Paddington station to the Slough station, is this, “We have met the enemy and they are ours.” The operator at Paddington presses down the buttons, 11 and 18, for signalizing upon the dial of the Slough station, the letter W. The operator there, who is supposed to be constantly on watch, observes the two needles pointing at W. He writes it down, or calls it aloud, to another, who records it, taking, according to a calculation given in a recent account, two seconds at least for each signal.

♦

Vail considered this inefficient. He was in a position to be smug.

As for Samuel Finley Breese Morse, his later recollections came in the context of controversy—what his son called “the wordy battles waged in the scientific world over the questions of priority, exclusive discovery or invention, indebtedness to others, and conscious or unconscious plagiarism.”

♦

All these thrived on failures of communication and record-keeping. Educated at Yale College, the son of a Massachusetts preacher, Morse was an artist, not a scientist. In the 1820s and 1830s he spent much of his time traveling in England, France, Switzerland, and Italy to study painting. It was on one of these trips that he first heard about electric telegraphy or, in the terms of his memoirs, had his sudden insight: “like a flash of the subtle fluid which afterwards became his servant,” as his son put it. Morse told a friend who was rooming with him in Paris: “The mails in our country are too slow; this French telegraph is better, and would do even better in our clear atmosphere than here, where half the time fogs obscure the skies. But this will not be fast enough—the lightning would serve us better.”

♦

As he described his epiphany, it was an insight not about lightning but about signs: “It would not be difficult to construct

a system of signs

by which intelligence could be instantaneously transmitted.”

♦

TELEGRAPHIC WRITING BY MORSE’S FIRST INSTRUMENT

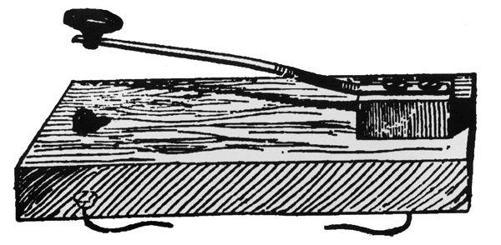

ALFRED VAIL’S TELEGRAPH “KEY”

Morse had a great insight from which all the rest flowed. Knowing nothing about pith balls, bubbles, or litmus paper, he saw that a sign could be made from something simpler, more fundamental, and less tangible—the most minimal event, the closing and opening of a circuit. Never mind needles. The electric current flowed and was interrupted, and the interruptions could be organized to create meaning. The idea was simple, but Morse’s first devices were convoluted, involving clockwork, wooden pendulums, pencils, ribbons of paper, rollers, and cranks. Vail, an experienced machinist, cut all this back. For the sending end, Vail devised what became an iconic piece of user interface: a simple spring-loaded lever, with which an operator could control the circuit by the touch of a finger. First he called this lever a “correspondent”; then just a “key.” Its simplicity made it at least an order of magnitude faster than the buttons and cranks employed by Wheatstone and Cooke. With the telegraph key, an operator could send signals—which were, after all, mere interruptions of the current—at a rate of hundreds per minute.

So at one end they had a lever, for closing and opening the circuit, and at the other end the current controlled an electromagnet. One of them, probably Vail, thought of putting the two together. The magnet could operate the lever. This combination (invented more or less simultaneously by Joseph Henry at Princeton and Edward Davy in England) was named the “relay,” from the word for a fresh horse that replaced an exhausted one. It removed the greatest obstacle standing in the way of long-distance electrical telegraphy: the weakening of currents as they passed through lengths of wire. A weakened current could still operate a relay, enabling a new circuit, powered by a new battery. The relay had greater potential than its inventors realized. Besides letting a signal propagate itself, a relay might reverse the signal. And relays might combine signals from more than one source. But that was for later.

The turning point came in 1844, both in England and the United States. Cooke and Wheatstone had their first line up and running along the railway from the Paddington station. Morse and Vail had theirs from Washington to the Pratt Street railway station in Baltimore, on wires wrapped in yarn and tar, suspended from twenty-foot wooden posts. The communications traffic was light at first, but Morse was able to report proudly to Congress that an instrument could transmit thirty characters per minute and that the lines had “remained undisturbed from the wantonness or evil disposition of any one.” From the outset the communications content diverged sharply—comically—from the martial and official dispatches familiar to French telegraphists. In England the first messages recorded in the telegraph book at Paddington concerned lost luggage and retail transactions. “Send a messenger to Mr Harris, Duke-street, Manchester-square, and request him to send 6 lbs of white bait and 4 lbs of sausages by the 5.30 train to Mr Finch of Windsor; they must be sent by 5.30 down train, or not at all.”

♦

At the stroke of the new year, the superintendent at Paddington sent salutations to his counterpart in Slough and received a reply that the wish was a half-minute early; midnight had not yet arrived there.

♦

That morning, a druggist in Slough named John Tawell poisoned his mistress, Sarah Hart, and ran for the train to Paddington. A telegraph message outraced him with his description (“in the garb of a kwaker, with a brown great coat on”

♦

—no

Q

’s in the English system); he was captured in London and hanged in March. The drama filled the newspapers for months. It was later said of the telegraph wires, “Them’s the cords that hung John Tawell.” In April, a Captain Kennedy, at the South-Western Railway terminus, played a game of chess with a Mr. Staunton, at Gosport; it was reported that “in conveying the moves, the electricity travelled backward and forward during the game upwards of 10,000 miles.”

♦

The newspapers loved that story, too—and, more and more, they valued any story revealing the marvels of the electric telegraph.

When the English and the American enterprises opened their doors to the general public, it was far from clear who, besides the police and the

occasional chess player, would line up to pay the tariff. In Washington, where pricing began in 1845 at one-quarter cent per letter, total revenues for the first three months amounted to less than two hundred dollars. The next year, when a Morse line opened between New York and Philadelphia, the traffic grew a little faster. “When you consider that business is extremely dull [and] we have not yet the confidence of the public,” a company official wrote, “you will see we are all well satisfied with results so far.”

♦

He predicted that revenues would soon rise to fifty dollars a day. Newspaper reporters caught on. In the fall of 1846 Alexander Jones sent his first story by wire from New York City to the Washington Union: an account of the launch of the USS

Albany

at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

♦

In England a writer for

The Morning Chronicle

described the thrill of receiving his first report across the Cooke-Wheatstone telegraph line,

the first instalment of the intelligence by a sudden stir of the stationary needle, and the shrill ring of the alarum. We looked delightedly into the taciturn face of our friend, the mystic dial, and pencilled down with rapidity in our note-book, what were his utterances some ninety miles off.

♦

This was contagious. Some worried that the telegraph would be the death of newspapers, heretofore “the rapid and indispensable carrier of commercial, political and other intelligence,”

♦

as an American journalist put it.

For this purpose the newspapers will become emphatically useless. Anticipated at every point by the lightning wings of the Telegraph, they can only deal in local “items” or abstract speculations. Their power to create sensations, even in election campaigns, will be greatly lessened—as the infallible Telegraph will contradict their falsehoods as fast as they can publish them.

Undaunted, newspapers could not wait to put the technology to work. Editors found that any dispatch seemed more urgent and thrilling with

the label “Communicated by Electric Telegraph.” Despite the expense—at first, typically, fifty cents for ten words—the newspapers became the telegraph services’ most enthusiastic patrons. Within a few years, 120 provincial newspapers were getting reports from Parliament nightly. News bulletins from the Crimean War radiated from London to Liverpool, York, Manchester, Leeds, Bristol, Birmingham, and Hull. “Swifter than a rocket could fly the distance, like a rocket it bursts and is again carried by the diverging wires into a dozen neighbouring towns,”

♦

one journalist noted. He saw dangers, though: “Intelligence, thus hastily gathered and transmitted, has also its drawbacks, and is not so trustworthy as the news which starts later and travels slower.” The relationship between the telegraph and the newspaper was symbiotic. Positive feedback loops amplified the effect. Because the telegraph was an information technology, it served as an agent of its own ascendency.

The global expansion of the telegraph continued to surprise even its backers. When the first telegraph office opened in New York City on Wall Street, its biggest problem was the Hudson River. The Morse system ran a line sixty miles up the eastern side until it reached a point narrow enough to stretch a wire across. Within a few years, though, an insulated cable was laid under the harbor. Across the English Channel, a submarine cable twenty-five miles long made the connection between Dover and Calais in 1851. Soon after, a knowledgeable authority warned: “All idea of connecting Europe with America, by lines extending directly across the Atlantic, is utterly impracticable and absurd.”

♦

That was in 1852; the impossible was accomplished by 1858, at which point Queen Victoria and President Buchanan exchanged pleasantries and

The New York Times

announced “a result so practical, yet so inconceivable … so full of hopeful prognostics for the future of mankind … one of the grand way-marks in the onward and upward march of the human intellect.”

♦

What was the essence of the achievement? “The transmission of thought, the vital impulse of matter.” The excitement was global but the effects were local. Fire brigades and police stations

linked their communications. Proud shopkeepers advertised their ability to take telegraph orders.

Information that just two years earlier had taken days to arrive at its destination could now be there—anywhere—in seconds. This was not a doubling or tripling of transmission speed; it was a leap of many orders of magnitude. It was like the bursting of a dam whose presence had not even been known. The social consequences could not have been predicted, but some were observed and appreciated almost immediately. People’s sense of the weather began to change—weather, that is, as a generalization, an abstraction. Simple weather reports began crossing the wires on behalf of corn speculators:

Derby, very dull; York, fine; Leeds, fine; Nottingham, no rain but dull and cold

.

♦

The very idea of a “weather report” was new. It required some approximation of instant knowledge of a distant place. The telegraph enabled people to think of weather as a widespread and interconnected affair, rather than an assortment of local surprises. “The phenomena of the atmosphere, the mysteries of meteors, the cause and effect of skiey combinations, are no longer matters of superstition or of panic to the husbandman, the sailor or the shepherd,”

♦

noted an enthusiastic commentator in 1848: