The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu (14 page)

Read The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu Online

Authors: Dan Jurafsky

The original meaning of the word

toast

was bread that had been grilled by the fire, from the popular Latin

tost re

re

(to grill). I’m a fan of toast; my invariant breakfast of a toasted bagel and a cup of coffee is a source of amusement for Janet, whose Cantonese sensibilities lead her to believe that all meals can be improved by a little bacon. And thick slabs of artisanal toast with pumpkin butter or homemade jam are the latest breakfast trend at San Fransisco cafes like the Mill. The association of toast solely with breakfast, however, is purely modern.

Until the seventeenth century, for example, wine and ale were often drunk with a piece of toast in it. This tradition is quite old; the Elizabethans did it too, as we can see from Shakespeare’s

Merry Wives of Windsor

: “

FALSTAFF

. Go fetch me a quart of sack; put a toast in ’t.” While it seems quite strange to us now, the toast was used to add flavor and substance to the drink, and was often spiced with herbs like

borage

, a sweet-tasting herb that is no longer in common use, and with sugar.

In the seventeenth century, just as this tradition of flavoring wine with toast was actually beginning to die out, the custom developed at English dinners to have the whole table drink to someone’s health. And then someone else’s. (And then again. All that drinking doesn’t seem very healthy to me, but as my British friends point out, I come from a nation founded by Puritans. Indeed, the Puritans of the time thought it was a bad idea too, and railed against the “drinking and pledging

of healthes” as

“sinfull, and utterly unlawfull unto Christians.”

) Frequently these

toasts were made to the health of a lady

, and the favored lady became known as the

toast

of the company.

A report from the time

suggests that the term was used because she flavored the party just as the spiced toast and herbs flavored the wine. Popular ladies “grew into a toast” or became the “toast of the town,” as we see in this (snide?) comment from a gossip magazine of 1709:

A Beauty, whose Health is drank

from Heddington to Hinksey, . . . has no more the Title of Lady, but reigns an undisputed Toast.

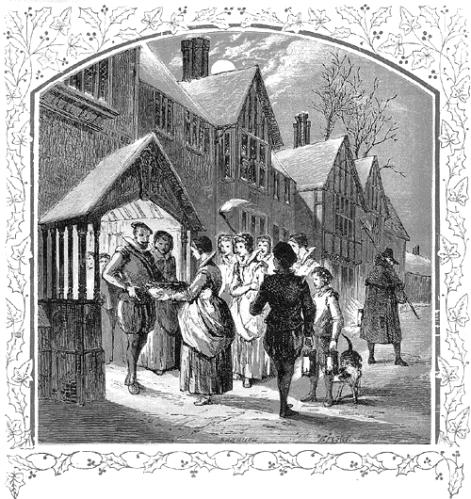

A Carol for a Wassail Bowl

,

by the Victorian illustrator Myles Birket Foster

One of the things the Elizabethans drank with toast was called wassail. Wassail was a hot spiced ale, especially one that was brought in on the Twelfth Night of Christmas and offered to the company from a wassail bowl. In the early 1600s, Christmas carols describe the tradition of women carrying the wassail bowl from door to door while singing songs and soliciting donations.

In another wassail tradition,

in the apple-growing West of England

, people would “wassail the trees,” placing

a piece of toast soaked in cider in the trees

and singing around the trees as a good luck ritual. For this reason some wassail recipes have cider or apples in them in addition to the hot ale. Here’s one:

4 baking apples, cored

cup brown sugar

½

cup apple juice

1

½

cups Madeira

1 bottle ale (12 ounces)

1 bottle hard apple cider (22 ounces)

1 cup apple juice

10 whole cloves

10 whole allspice berries

1 cinnamon stick

2 strips orange peel, 2"

1 teaspoon ground ginger

1 teaspoon ground nutmeg

Preheat oven to 350 degrees. Put cored apples in a glass baking dish and fill each with brown sugar. Pour apple juice (

½

cup) into baking dish and bake apples until tender, about an hour.

Meanwhile put cloves, allspice, cinnamon, and orange peel into cheesecloth bag or mesh strainer.

Put ale, cider, apple juice (1 cup), and Madeira into a heavy pot or slow cooker and add spice bag, ground ginger, and nutmeg. Gently simmer (do not boil) while apples are baking.

Add apples and liquid from baking dish into pot. Ladle into cups and serve.

The word

wassail

was first used to describe the drink in 1494, in the days of Henry VII. But the drink itself comes from the earlier sweetened ales of medieval Britain. Wine or spiced wine and cider were all conventional back then but ale was perhaps the most prevalent, sometimes in the form of bragget, an ale sweetened with honey or mead. Ale in medieval England was a dark brew made of malted barley and other grains but, unlike modern beer or ale, made without hops. As I mentioned above, hops are a preservative, so without them (their usage was only adopted from the Netherlands in the fifteenth/sixteenth century) ale went bad very quickly and so was drunk fresh, usually within a few days of brewing. Ales were a safe drink because they were made of boiled water, and many ales had a low alcohol content, with the result that everyone drank quite a lot of them in the Middle Ages and ale was thus an important source of calories and nutrients for the general population.

The idea of putting toast in the ale is even older. In the Middle Ages

slices of toast soaked in wine, water, or broth, called

sops

, were often used as a way to add heat, flavor, and calories to hot liquids like broth or wine. The most common meal of the Middle Ages, the thick

one-pot stews called

pottages

, were generally served over slices of hot toast or bread.

In

The Canterbury Tales

, Chaucer’s Franklin, a hearty old epicure whose house “snowed of meat and drink,” loved to have a sop in his morning wine (

“wel loved he by the morwe a sop in wyn”

). The earliest

written recipes mentioning toasted bread or toast in English all describe slices of bread toasted and then served “all hot” soaked in wine and spices, like these recipes for

“sowpes in galyngale”

from the 1390

Forme of Cury

, the first English cookbook, written by the master cooks of King Richard II, or “soups dorye” from a fifteenth-century cookbook:

| Sowpes in galyngale . Take powdour of galyngale, wyne, sugur and salt; and boile it yfere. Take breded ytosted, and lay the sewe onward, and serue it forth | | [ Sops in galangal . Take galangal powder, wine, sugar, and salt, and boil together. Take toasted bread, pour the sauce over it, and serve it forth] |

| | ||

| Soupes dorye . . . take Paynemayn an kytte it an toste it an wete it in wyne | | [ Golden sops . . . Take payndemayn (white bread) and cut it and toast it and wet it in wine] |

In fact

the word

sop

, perhaps via its

sixth-century late Latin relative

suppa

, gave rise by the tenth century to the Old French word

soper

(to have supper) and

soupe

, from which

come our words

supper

and

soup

. Soup thus first meant the soaked toast, and then generalized to mean the broth eaten with it, and supper meant the light evening meal of sops or soup, as opposed to a heavier midday “dinner.” In the United States, the word was retained in various regional dialects with various slightly different meanings. As a young child in New York,

supper

was my word for the evening meal, and I remember moving to California at the age of four, being laughed at by other kids for using this old-fashioned word, and informing my parents that we had to call the evening meal

dinner

.

The word

wassail

comes from the English of a thousand years ago, when you toasted someone’s health with wine or ale by saying

waes hael

(be healthy)

; the word

hael

is the ancestor of our modern words

hale

and

healthy

. English thus had a word just like Croatian

ževjeli

, French

santé

, or German

prost

.

The correct response to

waes hael

was

drink hael

(drink healthy). We know this because in 1180, the English monk and social critic Nigellus Wireker wrote that English students studying abroad

in Paris at the fancy new “university”

were spending too much of their time in “waes hael” and “drink hael” and not enough in their studies. I guess the fundamentals of university life have not changed in the last 900 years.

In some places complex ritualized toasts like the waes hael/drink hael (call-and-response) are deeply embedded in the culture. In the country of Georgia, for example, feasts are characterized by endless series of toasts with wine. There can be 20 or more toasts in an evening. Toasters around the room rise to toast the guest of honor, the Land of Georgia, families, the toastmaster (called the

tamada

), and so on.

In fact, to take a brief digression on the ancient origins of wine, converging evidence from biology, archaeology, and linguistics suggests that it is

in this same Caucasian region of modern Georgia or Armenia

that the wild grape was first domesticated and wine was made. The earliest known domesticated grape seeds have been found in this region, dating from 6000

BCE

. The region has the greatest diversity in wild grape genes, and DNA evidence suggests that the wine grape

vinis vinifera vinifera

was first domesticated from the wild grape

vinis vinferia sylvestris

here. The earliest chemical remains of wine come from jars found slightly farther east in a Neolithic village called Hajji Firuz Tepe in Iran’s Zagros Mountains, dating from 5000

BCE

. And some linguists believe that

*

γ

wino

(the * means this is a hypothesized proto word), the ancient word for wine in Kartvelian, the language family that includes Georgian, is the origin of the word for wine in neighboring language families like Indo-European (English

wine

and

vine

, Latin

vinum

, Albanian

vere

, Greek

oinos

, Armenian

gini

, Hittite

wiyana

) and Semitic (*

wajn

, Arabic

wayn

, Hebrew

yayin

, Akkadian

inu

). University of Pennsylvania researcher Patrick McGovern calls this idea

the “Noah hypothesis,”

after the biblical Noah, who planted

a vineyard on Mount Ararat (now in eastern Turkey at the Armenian border):

“And the ark rested

in the seventh month, on the seventeenth day of the month, upon the mountains of Ararat . . . and Noah . . . planted a vineyard.”