The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu (18 page)

Read The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu Online

Authors: Dan Jurafsky

Unlike most other Thanksgiving food names, the word

pecan

is Native American. English borrowed it from Illinois, a language of the Algonquin family. The original word was

pakani

, although we now pronounce our borrowing in many ways. My best friend from kindergarten, James, got married on a warm summer evening along the Brazos River of eastern Texas in what I was distinctly informed were “pickAHN” groves. But the word is PEE-can in New England and the Eastern Seaboard, pee-CAN in Wisconsin and Michigan, and something closer to peeKAHN in the west and many other parts of the country.

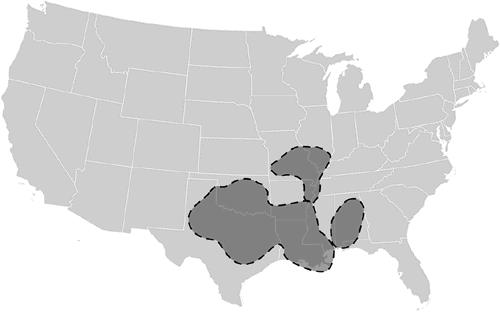

Why this difference? The region of the pronunciation pickAHN corresponds remarkably to the native range of the pecan tree. This is because the pickAHN pronunciation is closest to the original in the Illinois language (/paka : ni/). In other words, people in the area where the Illinois gave the word to English still use a traditional pronunciation, while dialects farther away have a modified pronunciation influenced by the spelling.

Two pecan maps

.

Top:

Rough outline of dialect regions where pickAHN is the dominant pronunciation (based on the research of Bert Vaux and Joshua Katz)

. Bottom:

Rough outline of natural habitat of the pecan tree (data from US Forest Service maps).

Although it’s not widely known, the guinea fowl came to America too, as part of the slave trade. Slave ships to the Americas included West African flocks as provisions, and slaves raised guinea fowl on small plots of land. The late

African American chef and food writer Edna Lewis

, the granddaughter of freed slaves, talks about guinea fowl as one of the important foods she grew up with in Freetown, Virginia, passed on “from generation to generation by African-Americans.” Her cookbook

The Taste of Country Cooking

describes traditional ways of stewing guinea fowl in clay pots that—based on

archaeological evidence of pots from early slave settlements

—probably date back to African Mandinka recipes for stewing guinea fowl in earthenware pots hundreds of years ago in West Africa.

So the real message of turkey is not that Portuguese trade secrecy caused sixteenth-century Europeans to confuse two birds, although it did, or that the turkey was traded in Europe’s first commodities exchange building, although it probably was, or even any of the fantastic myths about a collection of spices being blown by the wind into a seventeenth-century stockpot in Puebla, Meleager’s sisters being turned into guinea fowl, or Pilgrims inviting Massassoit for a Thanksgiving turkey dinner.

The real meaning of our Thanksgiving foods is that the Africans and the English managed, despite the horrors of slavery and the terrible hardship of exile, to bring the food of their homelands to help create the cuisine of our new country, just as the Native Americans and the Spanish, despite struggles and massacres and suffering, managed to merge elements of their cuisines to create the mestizo mole poblano de guajolote that helps preserve the food culture of their ancestors.

That’s another beautiful myth about America, and maybe this is finally one we can believe: that we’ve created something truly extraordinary in our stone-soup mestizo America by throwing into the pot, each of us, ingredients from the beautiful traditions our grandmothers and grandfathers passed down to us.

YOU CAN ALWAYS

GET

a good argument going in San Francisco by asking people for their favorite taqueria. I lean toward the

carnitas

at La Taqueria on Mission, but our friend Calvin can be pretty eloquent on the subject of the

al pastor

at Taqueria Vallarta on Twenty-Fourth. San Franciscans are similarly contentious about the best dim sum, and have been politely disagreeing about tamales since the 1880s, when the city was famous for the vendors plying the streets every evening with

pails of hot chicken tamales

. (Some things, of course, are simply not a matter of opinion, like the best place for roast duck—it’s Cheung Hing out in the Sunset, but don’t tell anybody else, the line is already too long.)

It’s not just San Francisco. You can’t go on the Internet these days without stumbling over someone’s lengthy review of a restaurant, wine, beer, book, movie, or brand of dental floss. We are a nation of opinion-holders. Perhaps we always have been: in De Tocqueville’s prophetic study of the American character, the 1835

Democracy in America,

he noted that in the United States “public opinion is divided into a thousand minute shades of difference upon questions of very little moment.”

Consider online restaurant reviews, those summaries of the wisdom of the crowd that have become a familiar way to discover new places to eat. Take a look at this

sample from a positive restaurant review

(a rating of 5 out of 5) on Yelp (modified slightly for anonymity):

I LOVE this place!!!!! Fresh, straightforward, very high quality, very traditional little neighborhood sushi place. . . . takes such great care in making each dish . . . You can tell the chef really takes pride in his work. . . . everything I’ve tried so far is DELICIOUS!!!!

And here are bits of one negative review (a rating of 1 out of 5):

The bartender was either new or just absolutely horrible . . . we waited 10 min before we even got her attention to order . . . and then we had to wait 45—FORTY FIVE!—minutes for our entrees . . . Dessert was another 45 min. wait, followed by us having to stalk the waitress to get the check . . . he didn’t make eye contact or even break his stride to wait for a response . . . the chocolate soufflé was disappointing . . . I will not return.

As eaters we use reviews to help decide where to eat (maybe give that second restaurant a miss), whether to buy a new book or see a movie. But as linguists we use these reviews for something altogether different: to help understand human nature. Reviews show humans at their most opinionated and honest, and the metaphors, emotions, and sentiment displayed in reviews are an important cue to human psychology.

In a series of studies, my colleagues and I have employed the techniques of computational linguistics to examine these reviews. With Victor Chahuneau, Noah Smith, and Bryan Routledge from Carnegie Mellon University,

my colleagues on the menu study

of Chapter 1, I’ve investigated a million online restaurant reviews on Yelp, from seven cities (San Francisco, New York, Chicago, Boston, LA, Philadelphia, Washington), covering people’s impressions between about 2005 and 2011, the same cities and restaurants from our study of menus.

With computer scientists Julian McAuley and Jure Leskovec

, I looked at 5 million reviews written by thousands of reviewers on websites like BeerAdvocate for beers they drank from 2003 to 2011.

As we’ll see, the way people talk about skunky beer, disappointing service, or amazing meals is a covert clue to universals of human language (like the human propensity for optimism and positive emotions and the difficulty of finding words to characterize smells), the metaphors we use in daily life (why drugs are a metaphor for some foods but sex is a metaphor for others), and the aspects of daily life that people find especially traumatizing.

Let’s start with a simple question. What words are most associated with good reviews, or with bad reviews? To find out, we count

how much more often a word occurs in good reviews

than bad reviews (or conversely, more often in bad reviews than good reviews).

Not surprisingly, good reviews (whether for restaurants or beer) are most associated with what are called

positive emotional words

or

positive sentiment words

. Here are some:

love delicious best amazing great favorite perfect excellent awesome wonderful fantastic incredible

Bad reviews use

negative emotional words

or

negative sentiment

words:

horrible bad worst terrible awful disgusting bland gross mediocre tasteless sucks nasty dirty inedible yuck stale

Words like

horrible

or

terrible

used to mean “inducing horror” or “inducing terror,” and

awesome

or

wonderful

meant “inducing awe” or “full of wonder.” But humans naturally exaggerate, and so over time people used these words in cases where there wasn’t actual terror or true wonder.

The result is what we call

semantic bleaching

: the “awe” has been bleached out of the meaning of

awesome

. Semantic bleaching is pervasive with these emotional or affective words, even applying to verbs

like “love.”

Linguist and lexicographer Erin McKean notes

that it was only recently, in the late 1800s, that young women began to generalize the word

love

from its romantic core sense to talk about their relationship to inanimate objects like food. As late as 1915 an older woman in L. M. Montgomery’s

Anne of the Island

complains about how exaggerated it was that young women applied the word to food:

The girls nowadays indulge in such exaggerated

statements that one never can tell what they do mean. It wasn’t so in my young days. Then a girl did not say she loved turnips, in just the same tone as she might have said she loved her mother or her Saviour.

Semantic bleaching is also responsible for meaning changes in words like

sauce

or

salsa

from their original meaning of “salted,” but I am getting ahead of myself. For now there’s much more to learn from reviews.

Let’s start with the negative reviews. Consider the very specific and creative words used to express dislike (

sodalike

,

metallic

,

wet dog water

,

force-carbonated

,

razor thin

) in this strongly phrased negative beer review from BeerAdvocate:

Clear light amber with a sodalike head of white that immediately fizzles to nothing. Very sodalike appearance. Aroma is sweet candy apricot with slight metallic wheat notes. Flavor is wet dog water infused with artificial apricot. Bad, bad, bad. Mouthfeel is razor thin, watery, and highly force-carbonated. Drinkability? Ask my kitchen sink!

My colleagues and I automatically extracted the positive and negative words. While reviewers generally called beers they disliked “watery” or “bland,” they tended to describe the way they were “bad” by using different negative words for different senses, distinguishing

whether the beer smelled or tasted bad (

corny

,

skunky

,

metallic

,

stale

,

chemical

), looked bad (

piss

,

yellow

,

disgusting

,

colorless

,

skanky

), or felt bad in the mouth (

thin

,

flat

,

fizzy

,

overcarbonated

).

By contrast, when people liked a beer, they used the same few vague positive words we saw at the beginning of the chapter—

amazing

,

perfect

,

wonderful

,

fantastic

,

awesome

,

incredible

,

great

—regardless of whether they were rating taste, smell, feel, or look.

The existence of more types of words, with more differentiated meanings, for describing negative opinions than positive ones occurs across many languages and for many kinds of words, and is called

negative differentiation

. Humans seem to feel that negative feelings or situations are very different from each other, requiring distinct words. Happy feelings or good situations, by contrast, seem more similar to each other, and a smaller set of words will do.