The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu (15 page)

Read The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu Online

Authors: Dan Jurafsky

These Semitic and Indo-European cultures that may have borrowed the word for wine also show early evidence for a concept related to toasting, the idea of

libation

. A libation, an offering of mead (a fermented honey beverage) or wine or oil poured to the gods before drinking, was central to Greek religion, appearing

as early as Homer

. At later Greek symposia,

a libation from the first

krater

of wine was poured to Zeus before drinking from it, from the second to the heroes, and so on.

These libations date back even earlier, to the ancestors of Greek culture, the Indo-Europeans, who poured libations for the gods to avert bad fate. We know this from linguistic evidence; languages across the Indo-European language family have many words for libation, often linked with words relating to health, security, or guarantees. Thus Greek

spendo

and Hittite

spand

indicates a wine libation that is poured while asking the gods to guarantee someone’s security or safe return, while the related Latin

spondeo

means “to guarantee,” from which we get our word

spouse

, from the Roman marriage ceremony in which one promises to guarantee the security of one’s spouse.

The root *

g’heu

(

pour

)

is the ancestor of Latin

fundere

(to pour, from which come English words like

fund

,

refund

,

found

,

fuse

,

suffuse

), and of Sanskrit

hav

-, used for the liquid offerings in Vedic ritual, and of Iranian

zav

-, meaning to make an offering, and Iranian

zaotar

, meaning priest.

Drink offerings seem to be just as old in the Middle East.

A 2400 to 2600

BCE

carving

at the British Museum shows a priest from the Sumerian city of Ur pouring a libation.

Similar images of libations

come from the third millennium

BCE

from the Akkadians, a Semitic people who took over Mesopotamia after the Sumerians.

The libations in Mesopotamia, both Sumerian and Akkadian, were generally with beer rather than wine. Grapes weren’t easy to grow this

far south, and beer, called

shikaru

in Akkadian, was the common drink. Shikaru was made from barley as beer still is today, but it was also often brewed together with honey or palm wine that could result in a higher alcohol content (more sugar to ferment means more resulting alcohol). The earliest extant written recipe in the world is an 1800

BCE

recipe for beer brewed with herbs and honey and wine in an ode to the Sumerian beer goddess Ninkasi:

Ninkasi, it is you . . . mixing . . . the beerbread with sweet aromatics.

It is you who bake the beerbread in the big oven, and put in order the piles of hulled grain.

It is you who water the earth-covered malt

It is you who soak the malt in a jar;

It is you who spread the cooked mash on large reed mats

It is you who hold with both hands the great sweetwort, brewing it with honey and wine.

You [add?] . . . the sweetwort to the vessel.

You place the fermenting vat, which makes a pleasant sound, . . . on top of a large collector vat.

It is you who pour out the filtered beer of the collector vat; it is like the onrush of the Tigris and the Euphrates

Libations are also recorded from a later Semitic people, the Hebrews, in the earliest parts of the Hebrew Bible, such as the drink offering Jacob makes in Genesis: “And Jacob set up a Pillar in the place where he had spoken with him, a Pillar of Stone; and he poured out a drink offering on it, and poured oil on it” (Genesis 35:14). This offering was usually of wine (Hebrew

yayin

) or oil, but could also be a drink called

sheker

, a word borrowed from the Akkadian word

shikaru.

Hebrew

sheker similarly meant beer

, or a modified beer with extra alcohol due to fermented honey or palm wine: “in the holy

place

shalt thou cause

the strong wine [sheker] to be poured unto the LORD

for

a drink offering” (Numbers 28:7).

We don’t know why the custom of libations with wine or beer developed. Wine may have been associated with health due to the antipathogenic properties of the alcohol or the infused herbs. Wine from 3150

BCE

jars produced in the southern Levant (modern Palestine or Israel) seems to have been

infused with antioxidant herbs

like savory, coriander, wormwood, or thyme. Some of these are the components of the spice mixture known as

za’atar

, still prevalent throughout the Levant. Wine, beer, oil, and flour (another common early libation) were also industrial foods, highly valued because of the effort necessary to process them, and convenient to spill out a bit as a sacrifice.

Alternatively, toasting may have begun as a way of strengthening ties of friendship between people; early Chinese writings prescribe toasts as part of elaborate social rituals. Other anthropologists have suggested that toasting and libation may have originally had to do with

the evil eye

, a superstition widespread in Indo-European and Semitic cultures that boasting about your good fortune can cause the gods to harm you. Because the evil eye was a dessicating force (withering fruit trees, or drying up cows’ milk), liquid was a kind of cure or placation for the Greek gods who might resent hubris in mortals. The curative power of liquids also explains the old folk custom of spitting three times to scare off the evil eye (opera singers still say

toi toi toi

before going on stage, a verbal representation of this spitting).

Toasting may also be related to health or appetite that Indo-European, Semitic, and many other cultures wish for before eating as well, like French

bon appetit

, Levantine Arabic

sahtein

(two healths), Yiddish

ess gezunterheit

(eat in health), or Greek

laki orexi

(good appetite).

In any case, the Hebrew word

sheker

had a continued life as the meaning “fortified beer” generalized to refer to any kind of strong drink. Saint Jerome in his fourth-century Latin Bible translation, the Vulgate, borrowed it into Latin as

sicera

, which he defined as beer, mead

, palm wine, or fruit cider. In the early Middle Ages

sheker

was borrowed into Yiddish

shikker

to mean “drunk,” while

in France the word

sicera

, now pronounced

sidre

, became the name of the fermented apple juice that became popular in France, especially in Normandy and Brittany. After 1066 the Normans brought the drink and the new English word

cider

to Britain.

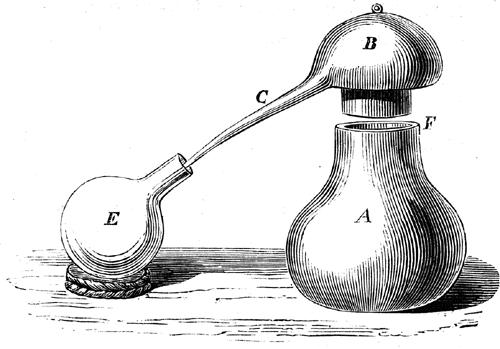

An alembic of the Middle Ages. The liquid to be distilled is placed in the cucurbit

A

and heated over a gentle fire. Alcohol has a lower boiling point than water, and rises as vapor into the still-head

B,

which is then externally cooled (for example, by cloth soaked in cold water), causing the condensed alcohol (or other distillate) to drip down the tube

C

into the collecting reservoir

E.

It was just at this time that

the technology of distillation was perfected

by Persian and Arab alchemists, extending the work of earlier Egyptian Greek and Byzantine alchemists. The

alembic

(from Arabic

al-anbiq

, from Greek

ambyx

; also the ancestor of the word

lambic

referring to the spontaneously fermented Belgian beer) is a flask whose lid has a tube coming off it; when a liquid is boiled in the flask, the vapor rises into the tube and drips out as it cools and condenses.

By the early Renaissance alcohol distillation began to spread west to Europe and east to Central Asia. In Western Europe, apple ciders and grape wines were distilled into eau-de-vies and brandies. Peruvians and Chileans produced their brandy Pisco by distilling wine. In southeast Europe, plum cider was distilled into the

rakia

that we toasted with at Marta’s wedding.

All this history, of course, is there in the words. The word

rakia

comes from ‘

araq

, meaning “sweat” in Arabic, a vivid metaphor for the condensing alcohol dripping from the spout of the still.

Other descendants of the word

‘araq

are used all over the world for the local distilled spirits. We already met

arrack

, the red rice liquor of Indonesia, in the previous chapter

,

and there are many others: the anise-flavored Levantine

arak

of Lebanon, Israel, Syria, and Jordan or

raki

of

Turkey

, Persian

aragh

, the gesho-leaf flavored

araki

of Ethiopia, the coconut liquor of Sri Lanka also called

arrack

, or Mongolian

arkhi

, distilled from fermented mare’s milk. What these areas have in common is their history of Muslim populations, contact, or influence, from Ottoman-controlled southeast Europe in the west through the Persian influence on the Mongols to Muslim Indonesia in the east. (Although intoxicants are banned in Islam, drinking of specific kinds of alcoholic beverages in various amounts was sometimes allowed and in any case seems to have persisted in different regions.) These words (and other Arabic words like

alcohol

) are thus a reminder of the important role of Arab and Muslim scientists in developing and propagating distillation and distilled spirits.

As for cider and shikker, they both still carry the phonetic traces of

shikaru

, the Akkadian honeyed beer and the world’s oldest written recipe, and this ancient method of getting higher alcohol content by fortifying beer with honey or fruit. In fact, the very earliest manmade alcoholic beverage we know of is a similar beer/cider mixture

of fermented honey, rice, and grape or hawthorn fruit whose traces have been

found on pottery from 7000 to 6600

BCE

in China’s Henan province.

In other words, the chamomile, thyme, and fruits of our hip modern cocktails and summer micheladas are not a new innovation at all, but the modern reflex of an ancient tradition that began with the world’s very first mixed drinks 9000 years ago, and continued through history with the Levantine thyme-infused wines and Mesopotamian honeyed beers of 2000

BCE

, the wassails of Henry VII, the toast-and-borage-spiced wine of eighteenth-century England, and our modern mulled ciders. And the strong hops flavors in modern IPAs bring to mind the barrels of India Pale Ale in the sweltering cargo holds of the East Indiamen crossing the equator to what were then called Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta.

Libations are still around too. Modern hiphop culture has a libationary tradition of “pouring one out”—tipping out malt liquor on the ground before drinking, to honor a friend or relative who has passed away—described in songs like Tupac Shakur’s “Pour Out a Little Liquor.” (It’s especially appropriate that malt liquor, a fortified beer made by adding sugar before fermenting, is itself another descendent of shikaru.)

Modern cocktail names have gotten more interesting, though. The bar Trick Dog in the Mission names drinks after Pantone colors or old 45 rpm singles, Alembic by the park serves a Sichuan pepper-infused Nine Volt, and the Lower Haight’s Maven has drinks with names like Widow’s Kiss and Nauti’ Mermaid, whose straightforward appeal to women and sex recalls those eighteenth-century tipplers whose drinking to the health of the “Lady we mention in our Liquors” first gave rise to the word

toast

, although now it’s as likely to be the women doing the toasting.

In any case, now that our Punch break is over, let’s talk turkey.

I LOVE THANKSGIVING,

when the rains finally begin to come to San Francisco and it feels almost like we have seasons. The streets are bustling with people buying ingredients for their mother’s fabulous stuffing or tamale or dessert recipes, and, most important, my choirs start to have their winter concerts. Last Thanksgiving I missed seeing various friends’ choir concerts, making me feel almost as much a musical Scrooge as Edgar Allan Poe, who famously said: