The Lightning Keeper (44 page)

Read The Lightning Keeper Online

Authors: Starling Lawrence

“Go now, it is almost time.”

Fowler Truscott, with Dr. Steinmetz steadying his elbow, made his way out onto the ice with champagne in one hand and extra glasses in the other. He bade his guests link arms and stand in a circle around the fire to listen for the bell, which followed almost immediately but was so muted by the falling snow that many were surprised when their host launched the first note of “Auld Lang Syne.”

The snow was falling faster now, and Harriet worried that she would miss her chance at the lake beyond the cleared ice. She skated up behind Toma, still standing at his place in the dissolving circle, and without a word took his arm in hers under the weightless warmth of the cape.

Toma was an apt pupil, and because her arm was always there he was soon able to match the rhythm of her glide. Around the fire they went; halfway through the third circuit she released his arm and made a turn, facing him now but floating away with her hand stretched out to him.

“That wasn't so hard, was it?”

“Can we stop before I fall down?”

“No turning back now. I will show you the rest of the pond.”

Voices and sounds were lost as abruptly as if a door had shut behind them; they glided along the shore guided by Harriet's memory and the dim fluorescence of falling snow, their blades making only a whisper against the intermittent musical percussions of the expanding ice.

Beneath the cape she held his arm to her waist. The grip of his hand on her forearm was fierce. How could she not have remembered that day in Pompeii, when she had stumbled on a piece of masonry and would have fallen but for the shock of his arm, strong and so warm against hers, and his hand. That innocence was years ago and so far away that it might be a memory of two different people. She sighed.

“Are you tired?”

“No, it is nothing. But if you hold my arm so you will leave me with a bruise. Let me show you how a man and a woman skate en paire.” She drew his right arm around her waist and put her hand over his, at the same time reaching out to the other hand. “Do you feel safe?”

“More than before.”

“Good. And now⦔ She eased his hand away from her waist and pushed hard off her right skate. For a moment she floated in front of him, her arms spread like a black swan rising from the water, then she settled back against his left arm.

“It is like⦔

“A dance?”

“Yes.”

Again she pushed ahead, now turning under his arm, and they were face-to-face with their hands crossed.

“Now what?”

“Either I turn back under your arm, or you turn under mine, and we shall be skating backward together.”

“I don't know how to turn. Or stop.”

“We'll save that for the next lesson.”

“When will that be?”

“Every night at midnight we shall meet here,” she said, laughing, “and in no time at all⦔

“And when the ice melts?”

“Toma, I'm sorry, I was only being silly.”

“There is only tonight, then.”

She said nothing, but his remark set her free. When they had skated away from the fire they entered a kind of limbo, another world, and now their isolation was perfect because time too had been stripped away. No past, no future, only this. Only tonight.

They had reached the eastern end of the pond, where a dark wall

plunged down through the ice. He stopped skating, thinking they must turn around, but she towed him on until they were within arm's reach of the wall. Then the rock was on either side and they skated through this gateway into an extension of the pond no larger than a ballroom.

“What magic is this? Do the rocks open at your command?”

“I call it the Pillars of Hercules; the water is very deep there, but shallow here. Look at all the cattails, and in a minute I'll show you the beaver lodge.”

“Where?”

“I'll show you.”

They skated slowly now, knowing that when they had explored this last reach of ice they would have to turn back.

“Is there no further wonder to see?” She squeezed the hand at her waist by way of reply and then he fell without a word of warning, tumbling sideways and pulling her down on top of him. In the sound of the shattering reeds she heard his head hit the ice.

His body had cushioned her fall. Only her knee had grazed the ice, but Toma did not move. “Tomaâ¦Toma?” She found his hat in the reeds. Should she try to put it back on? Would she hurt him by lifting his head? She did not know. She settled for sliding her fingers into his collar beneath the scarf to find his pulse. Her hand was unsteady: there might be a pulse, or not. Now she bent over him, her cheek to his lips. Was he breathing? He was.

It was the cold that she feared if she had to leave him here. Her fingers fumbled with the silver clasp of her cape. It snapped in her hands and a piece flew off into the reeds. She made a cocoon around his head and shoulders, trying not to move him, put her cheek against his and spoke his name in an urgent, strangled whisper.

He made a groan that curled up at the end into a question.

“Don't move, Toma, don't move until I can tell how you are hurt. Do you hear me?” In her happiness she wept, and when she felt his hands on her shoulders she cried harder.

“What is wrong?” His words were distinct and deliberate.

“You fell, Toma, you fell and hurt yourself.”

“And you are hurt also?”

“No, I am glad, justâ¦so glad.”

He moved as if he would get up. “Wait,” she said, “wait.” His arms came up around her and he held her.

“There.” She sat up and wiped her face on her sleeve. “Where does it hurt?”

“My head and my ankle.”

“Your skate must have stuck in a crack. Can you lift your head?” She slipped his fur hat back on and took the cape around her shoulders. “Do you think you can stand? Take my arms.”

Toma's ankle was twisted, not broken. They made their way back to the fire slowly, on three skates.

“We are alone. Did no one miss us?” His question caused Harriet to think, for the first time since they had left the fire, of anyone but Toma.

“If you can find my shoes I'll be off.”

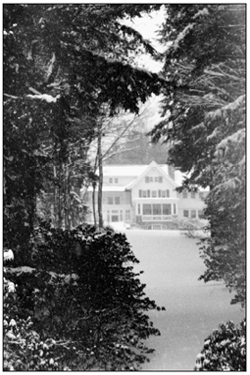

“You can't go anywhere. What if you fall again? There will be a bed for you in the house, somewhere.” He looked up at the house. Only the lighted windows could be seen through the snow: the dining room on the ground floor; then the landing on the staircase; above it to the right Dr. Steinmetz's bedroom. And higher still the small window that they both knew to be Olivia's.

“No. I will stay here in the cabin.”

“Of course,” Harriet replied quickly, wondering why she hadn't the wit to think of that in the first place.

There was still a fire in the hearth. Harriet pulled the long wicker chaise near and put the lap robes on it. Toma hobbled across the room with a bottle of champagne in one hand and two ham sandwiches in the other. He held them out to her.

“I can't. I must go.”

“Of course. You must go back. But you won't get far on those.” He pointed at her skates.

“It doesn't matter. My hands are too cold anyway. My glovesâ¦I don't know where they went.”

“Put your hands under your arms and sit down.” He knelt before her. “What do you call these things?”

“Eyelets.”

“I have never seen so many in one place.” He had one skate off now and rubbed her foot before putting on her boot.

“My hands are better now. I can do the other.”

“Warm enough to hold a sandwich? Go on.”

She ate part of the sandwich and made him eat the rest. She put her hands gently on his head and felt for the bump. “Poor you.”

She stood up when he was finished, and he stood as well, a bit nearer than he ought to be. She pushed him down onto the chaise. “You must not stand on that ankle, Toma, and I must go. Really I must.”

“Thank you for my lesson. For everything.”

How should such an evening end? She put her fingertips to his cheek, to the spot where her own had been, and wished him good night.

Â

“H

ARRIET, IS THAT YOU?

Thank God.” Lucy spoke from the stairwell. Where was everybody?

“The others, Lucy, have they gone home?”

“Home? Well, I suppose so. They aren't here.”

“And Fowler?”

“Fowler had to be helped up to bed by Cecil and Dr. Steinmetz. He'd had too much to drink. I came up just after midnight with Caroline, so I don't know any more than you do. Cecil was surprised not to find you with me, then he thought you must be in the bath. What the others thought I have no idea, but they left. Somehow I knew you were not in the house. And here you are.” The tone of her voice demanded an explanation.

“I was showing Toma how to skate. I didn't think everyone would leave so soon.”

“Yes. Cecil said that the last he saw of you, you were skating off into the night. I don't know how you could do it.”

“Do what, for Heaven's sake?”

“Look at yourself, Harriet. Just look.”

Harriet looked: at the broken clasp hanging by a thread; at the tawny down of cattail that clung everywhere to her black clothes; and, out of the corner of her eye, at a bit of reed that had stuck in her hair.

“He fell.”

“It doesn't matter what he did. A woman must look after her own reputation. No one else will if she does not.”

“No. No, I can see that quite clearly, thank you. But what I cannot understand is how you could speak to me this way, as if I had⦔

“That's exactly my point. As if you hadâ¦finish the sentence any way you like.”

“Lucy,” said Harriet, seized by a chill that altered her voice, “how can you say these things? What do you think happened? We were skating and he fell, that's all. I swear to you.”

“It doesn't matter what I think, or even what you didâor did not do. If Cecil noticed, then I tell you it must have been pretty obvious. I don't think he really believed you were in the bath at all.”

“I have told you the truth, Lucy. You cannot believe otherwise.”

“Can I not? You have been so preoccupied this whole week. I knew something was different, and I said so to Cecil. I just didn't know what.”

“I will not be spoken to this way, Lucy, or it is the end of a long and dear friendship. Your imagination disgusts me. I am going upstairs now, up to Fowler, and I shall pray that we both forget what we said.”

The desk in the office of the now defunct Bigelow Iron Company was almost as bare as when Amos Bigelow used it for his weekly calculation of the sun's meridian. And although the mirrors had not been cleaned or adjusted since the day of Horatio Washington's fatal accident, the one outside the window still caught the sun, casting its image on the ceiling, high or low according to the season, and for a few days a year around that sad anniversary the system worked as well as it ever had.

Toma was in a mood to be distracted. A chunk of rough rock sat in the middle of the desk, its color a clouded red. In direct sunlight it would bloom, revealing myriad faceted crystals of garnetite, but its significance was invisible, revealed only by the proximity of iron filings or a compass. Dr. Steinmetz had determined that the red rock contained the highest percentage of magnetite, and that Toma should pursue it at all costs in the excavations under Lightning Knob.

Excavating a tunnel in a straight line was a relatively simple proposition, though not without danger. But the new instructions were to follow the veins of this blood-hued rock, being careful not to disturb it, so that the linked lengths of iron could be set into it. By Steinmetz's calculation, following the magnetite would lead to a dramatic increase in the aerial's ability to attract lightning to the array of experimental protective devices.

The phone call from Stefan had come yesterday afternoon: an urgent delivery from Schenectady and new instructions. The equipment

on handâsome of it newly purchasedâwas inadequate to the job ahead, or unnecessary. Who knew where the red rock would lead them, or how much of it there was? The task was to follow a maze through solid rock, and explosives, even heavy machinery, were out of the question. At best they might use pneumatic drills, but much of the job was bound to be handwork. Steinmetz's calculations specified three thousand feet of ironâthe roots of his aerialâto be laid into the red rock and fixed by bolts. The timetable for completion was inflexible: the site must be ready by the first of June at the latest to coincide with the season of peak electrical activity. And in the meantime, starting now, or half an hour ago, there were endless costings and requisitions to sort out. Where was Harriet when he needed her?

It had been a quiet few days following the turn of the New Year. Toma knew that he could not expect to see Harriet in the office until her houseguests had departed, and the injury to his ankle confined him to Lightning Knob once he had made it up the mountain. On January 2, Dr. Steinmetz had come to inspect the excavation, as had been agreed at dinner on New Year's Eve. He seemed even more animated than usual, expressing febrile interest in every detail of the operation, running his hands over the blank walls at the bottom of the shaft where the tunnels would soon be started. Was he even then hatching the idea about the red rock? Later that day, on his way to chop ice in the stream, Toma had seen footprints in the snow on a path leading up the mountain. One set must belong to Steinmetz: he had seen the marks of that diminutive boot not three hours earlier. And whose could the other set be if not Harriet's?

It had been a week now. The fact that they had missed each other in the office several days running seemed an unlikely coincidence. He thought about the night on the ice. Could he have done differently? Had he offended her? But there was no offense: there was only knowledge. He had been a witness to somethingâhis own feelings were no transgressionâand that must be the reason for this absence that felt so like a sentence.

On the pretext of deliberating upon the instructions from Schenectady, he waited for her, drumming his fingers on the table, glaring at the rock as if he might vaporize it, startling at the sound of the noon siren, and all the while trying to fuse the sweet, dangerous knowledge

of what had happened on the lake to the innocence of their afternoons in this office.

He was stoking the stove when the door opened, and it was clear at a glance that her surprise in finding him there had little pleasure in it. He stood up, dusted off his hands on his trousers, and nodded at her. Her expression softened at this display of awkward deference.

“I did not expect to see you, Toma. We must talk.”

“Will you sit down?”

“No. Yes, of course I will. I don't know what's wrong with me. The last few days have been so strange. Everyone is gone and the house is a tomb.”

They sat at the desk in their familiar positions, so that she was facing the wall and windows at his back rather than the center of the desk. He waited for her to speak; and when she did not, he drew her attention to the red rock and related what he had heard from Steinmetz.

She seemed to be listening, but made a tangential comment. “I wish he were here, Dr. Steinmetz. He would tell me what to do.” Now it was Toma's turn to say nothing.

“Toma, I have been thinking that I must go away.”

“Where?”

“Washington. I must be with Fowler, at least for a while.”

“Is he unwell?”

“No, it's not that.”

“Then what?”

“He is my husband, for Heaven's sake. Please don't make me explain all this.”

“If you have to go. Stefan will help me here. We'll manage. But will you come back?”

“Of course I shall come back. This is my home, not Washington. My father⦔

“But you are leaving.”

“I have been thinking about this, and my mind is made up. I must do it, and that's all there is to be said.” She spoke to her folded hands and would not look at him, and so he was free, as he seldom had been, to study her face in this different mood. He had never before seen the crease that now interrupted the straight dark line of her brow.

“I came to see you in Washington. Do you remember?”

“I certainly do.” She smiled at the memory. “You had just come from the patent office, and you were radiant. You told me you would be rich.”

“Did I? What a foolish thing to say.”

“I didn't think so. I was proud of you.”

“I remember that you sang, and that we sat in the front room as the sun went down.”

“It will be different now, in winter, and without Papa.”

“May I write to you?”

“About the lightning project?”

“Of course.”

“There can't be any harm in that. It will be good to have news from home.”

“Can you spare a few minutes to talk about this?”

He took the rock in his hand and the folded paper beneath it skidded a few inches, catching her eye. She opened it, thinking it was a note from Steinmetz.

“Twenty thousand dollars, Toma?”

“I keep forgetting to put it in the bank. I must do that today.”

“But what is it for? This is a great deal of money.” He was surprised at her reaction. The check had ceased to interest him.

“It is for the wheel. They have made a licensing arrangement.”

Her eyes filled with tears, which she made no attempt to hide. She started to speak and still the tears came. She drew an uneven breath, covering her eyes, an uncharacteristic gesture that drew his attention to the size of her hand, nearly as large as his own, and its pale, elegant articulation. He asked, gently, what was wrong.

“Oh, Toma, think what this money would once have meant.”

Â

H

ARRIET'S IDEA OF VISITING

Washington had been prompted by Lucy's letter, still propped against the silver correspondence rack on her desk when she sat down with her tea at the end of the afternoon.

Harriet had opened the letter thinking that it was late for a thank-you note, and there were too many pages. But after the pleasantries and a paragraph of doubtful sincerity apologizing for her sharp tone on

New Year's Eve, Lucy launched into her theme: the perilous state of Harriet's marriage and the steps that must be taken.

Harriet had gone to the office earlier than usual to get away from her desk and the letter she was trying to draft, and her conversation with Toma was a kind of rehearsal for what she must now write. It had all sounded reasonable enough when she spoke the wordsâmore so than when laid out on these blue pagesâand there had been an element of confession in those few minutes. How else could she ever speak to Toma about what had happened? And how could she be silent? It had been so much easier to talk to Lucy about what had

not

happened. She had done nothing wrong: there was the truth that would guide her.

She put down the pen and picked up Lucy's letter again. Lucy was more subtle on paper than she had been in person, and her observations on the difficulty of marriage were candid and therefore persuasive. She did not reproach Harriet; in fact, as Harriet realized on this new reading, she did not even make reference to New Year's Eve beyond her apology. But she did take as a given the physical coldness of the Truscott marriage, which seemed to her remarkable in light of Fowler's long absence. Cecil, she wrote, was sometimes away for a few days, shooting or playing golf, but when he returned to her bedâ¦Harriet thought the point could be made, and understood, without resorting to that word.

Had the signs been so obvious? It must have been something she'd saidâ¦or doneâ¦or not done? How could Lucy know these things? How could she put her finger on the thoughts that had occurred to Harriet during her long vigil in Fowler's bed on Christmas night?

“Dear Fowler,” she began again and could get no further. This was ridiculous: her first attempt had been a page and a half long; the second effort failed after two paragraphs. And now, apparently, she had nothing at all to say. Every reason she thought of sounded forced or false and the very act of writing them down seemed an admission of the failure of her marriage. What had she not done that she ought to have done? And what would she not have done? Well, the thing she could not do, as evidenced by the balls of blue paper in the wastebasket, was to announce to her husbandâin either mode of confession or seduc

tionâthe intention of her visit, which Lucy rendered in the appalling phrase of seizing the bull by his horn. “It doesn't matter,” wrote Lucy, “whose fault it is. But it matters very much that you take this blame on yourself, for that is the only way forward.”

Perhaps it was the idea of taking the blame on herselfâor even the phraseâthat made it difficult to put the right words on the paper, for she was inevitably reminded of Lucy's harsh judgement the night of the skating party. That was where she drew the line. She had little pride left when it came to her marriage; every trip to his bed was a humiliation of sorts. But she would not admit that she had done anything wrong.

In the end it was a morbid reflection on what might happen to her father in her absence that saved Harriet from paralysis. She was thinking about what would be good for Amos Bigelow when she remembered the day she had promised him a surprise. She had brought him the ledger, but he had hoped it would be a child. She could do anything, even find a way to write this wretched letter, if it served the end of his happiness.

â¦And in the middle of this revelry, this

Winterfest

, began the snow, as I had anticipated. I was standing on the dock with Senator Truscott, but still exhilarated after riding in the chair over the frozen depths, perhaps even a little giddy from that experience, and the sensation of the very fine snow dust on my face as I gazed blind into the heavens was the trigger to a kind of mystical vision or a trance. I do not know if that is the right word, but for several minutes I was unaware of my surroundings, because suddenly Truscott was rattling the champagne flutes in my ear and telling me it was almost midnight.

My dear Mr. Coffin, I hope you will not be alarmed by this disclosure, but it touches on the work we have begun and on that which grows like a submarine crystal in my imagination.

In my vision I was witness to an electrical disturbance on the promontory where the tower is being built and the shaft sunk, but rather than the heat of summer, it was somehow that same night, New Year's Eve. It must have been the sensation of those featherlike flakes that set me thinking along those lines, for I had just read Göchel's discourse on the contrasting atmospheric discharge associated with the type of snowânegative for tiny flakes, positive for the largest onesâand I imagined the possibility of provoking electrical disturbances in the

dead of winter, given the right circumstances and the right equipment. This premonition was confirmed by my visit to the tunnel shaft. Years of working with circuits have made me sensitive to imperceptible electrical impulses, and I recognized something when I laid my hands on the red rock 45 meters down in that shaft. It was the electromagnetic potentiality of the mountain that I sensed, as perhaps the nascent statue in the block of stone communicates itself to the artist.

I have this day sent off to Beecher's Bridge the Exner gold-leaf electroscope to measure the potential gradient above Lightning Knob. I believe we shall soon have the beginnings of a scientific explanation of the unusually high incidence of electrical activity in Beecher's Bridge.

And I have another surprise to share with you. On New Year's Day I made an expedition with Mrs. Truscott up the mountain to the high lake that we tried to find last summer without success. There was some difficulty in the ascent, but the snowfall was not great, and once we were up on the plateau we made good progress; at last we broke through the defenses of the surrounding alders onto the ice of Dead Man's Lake, which is roughly 500 meters wide and perhaps twice as long. From the thick growth around the shore one would conclude that this is a mere runoff or catchment pond of the sort commonly found in the North West Corner; but local legend describes it as dangerously deep, as the name might indicate.

With the hatchet, and Mrs. Truscott's assistance, I chopped two holes in the ice, 200 paces apart, and measured a depth of 48 meters by the plumb line in one, and 35 in the other. Rough calculations, of course, but there is certainly enough water here for the pump-storage facility.

The outing was an opportunity to speak again to Mrs. Truscott about the work that we envision, and I think I am making progress in spite of her ambivalence. She proposed the idea that man should be the steward of God's creation, and as gently as I could I pointed out that since the existence of God was in no way provable, her “idea” amounted to a sentimentality, quite powerful, but inadmissible in a scientific discussion. The admirable Mrs. Truscott, as deft in argument as she is handy with an axe, asked if I would mock her religion. Not unless you mock my agnosticism, I replied. It was a friendly and spirited exchange, and I made the point that in realizing the potential of nature, man serves both God and Science.

She took pleasure in being the one to break through the ice in the first hole and take the sounding. It was a day of luminous clarity, and with her face

glowing from physical exertion and the stimulation of our exchange she seemed a figure of legend. There was such a sense of satisfaction and connection in this moment, and it occurred to me that had it been my last instant of existence, I should have felt my life somehow complete.

My revised estimates on the cost of the pump-storage experiment will follow within the week, and if it is at all persuasive to your colleagues, you may tell them that I stand ready to contribute the last pennies in my bank account to the effort. What am I compared to the mountain, or to this work?

My kindest regards, etc.

Steinmetz

Â

p.s. It has been brought to my attention by Professor Steffens that between 1850 and 1910 the number of houses struck by lightning per year per million has tripled. It is tempting to read a superstitious significance into this interesting statistical aberration.