The Lightning Keeper (42 page)

Read The Lightning Keeper Online

Authors: Starling Lawrence

The folded cheque had fallen to the floor while Toma read the note. There was Coffin's signature, and there the notation of the amount. He wondered if this meant that he was rich.

When he had finished his second slice of mince pie, and chased it with a glass of fiery apple brandy, he asked if the snow had stopped falling.

“It has, dear, but we've a bed for you if you want. Perhaps you'd better stay if you're onto the applejack.”

Should he tell her his news? Instead he took her hand and said, “If you could see how we drink the plum brandy in my country you would have no fear for me. My supper was a feast. Thank you.”

He paid his bill and left five dollars, which he said was for the bath and for his clean clothes. That's too much, she protested, much too much. And your kindness, he said.

The stars and a crescent moon lighted his way up the mountain, and the leather webbing set with screws that he had put over his boots gave him sure footing in the snow. Near the top he glanced back at the lights of the Truscott house below and wondered how much it had cost to build.

Â

H

ARRIET

T

RUSCOTT LAY IN

bed beside her husband, who had fallen asleep. If she could go back to her own bed and her own room she would be more likely to fall asleep, but Fowler would wake sometime in the night to find her gone and be puzzled, or disappointed, or offended. All she knew was that she was stuck here for the next eight hours owing to her own foolish expectations. She should know better than to misinterpret his expansive pleasure in the dinner, the embrace of his home, her company. It did seem to her that he drank more now, and made no excuse for it. The pressures of work must be overwhelming, she thought, making his excuse for him.

She had the book of Emerson's essays open and propped up on the little pillow, but she could not read any more than she could fall asleep.

She was preoccupied with the logistics of Lucy's arrival three days hence. Lucy and Cecil and the baby would have to have her bedroom, with Caroline and the nurse in the yellow room. The single bedroom with the writing table must be kept for Dr. Steinmetz, as he had expressed such satisfaction with that mattress and his view of the pond. It wasn't perfect, but there it was. If Olivia were not so neccesary she might be sent home and the nurse could go upstairs, Lucy to the yellow room, and she would have her own bed. A week sharing Fowler's bed should not be a hardship, she told herself. But it crossed her mind how much easier it would be in some ways if he were called back to Washington.

When she had juggled these possibilities several times her mind drifted back to her parting from Toma. She regretted having raised the subject of his solitary Christmas, because that could only make matters worse, and it might appear that she was prying. The day before she had asked Olivia if she needed to go homeâbe away was how she put itâover the holidays and the answer was simply no. And then she had left the office so abruptly, quite like a guilty person.

The mountain rose just beyond her window, cowled in new snow. How many paces would it be from where she lay to the top of the Knob?

She got up and went to the window, easing it open, taking the sharp air on her flesh like a penance. There was no light on the crest as there sometimes was, and she thought: What if he could see me here in my nightgown, looking up to him? Well, what of it? She might as well be honest with herself.

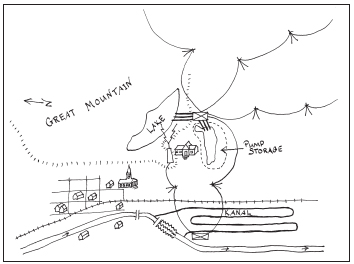

Steinmetz's sketch of Great Mountain

Inside the boathouse

Despite her careful plans, and her middle-of-the-night revisions to those plans, Harriet's imagination of the New Year's house party did not prepare her for the reality.

Dr. Steinmetz was the good news: his humor and patience were more than equal to the trial of Lucy's children and Amos Bigelow. In the morning, while Fowler was dressing and long before Lucy had stirred, he went down in his slippers and robe to fetch a pot of coffee, then retired to his room to read and smoke. At the table he sat next to Amos Bigelow and made gallant, unrewarded conversation. And Caroline, a temperamental and irritating child, was charmed to silence when Dr. Steinmetz, with the lamp at his back, made shadow shapes of animals on the wall. Afterward, Caroline sat in the corner, her hands clasped, practicing her own shapes.

The odd thing was how little pleasure Harriet took in Lucy's company. Having a new baby and a toddler was exhaustingâYou can have no idea, said Lucyâbut she did have the resources of the nurse, her maid, and also Cecil, who, whatever else might be said of him, was attentive to the children. In the early morning he would walk the baby up and down the hall while his wife slept.

Lucy's peevishness was not to be appeased. She could not sleep properly in that bed: she and Cecil had twin beds. She complained of Caroline's behavior, but left others to deal with her, and she seemed rather short with Cecil himself. When he ventured a comment at the

table Lucy, as often as not, cut him off as if he had not spoken. Harriet did not find Cecil interesting, nor was he energetic, except in the matter of walking the baby, but she liked him well enough, and felt sorry for him.

It was difficult to find any time for those long talks that Harriet remembered and looked forward to, and it seemed to her that Lucy might have tried a little harder to create the opportunity. Perhaps those confidences were something they had now, at last, outgrown. The one chat they'd had hardly rose to the level of the meaningful: Lucy was preoccupied with her sore nipples. Harriet suggested she consult Olivia, who was knowledgeable about home remedies and herbal treatments.

“Oh,

her

,” said Lucy, with arch emphasis. “I did wonder where she came from. Very striking; too striking, I think, and a bit surly. Perhaps you should have a word with her.” And that was the end of their conversation.

Fowler Truscott was in an odd humor, and Harriet, in her few moments of idleness, tried to put her finger on what had changed in him. The least drastic interpretation was that he had put on the mask of the jolly innkeeper as a defense against the number and variety of his guests. Certainly when it came to filling glasses and supplying cigars he was perfect. He and Dr. Steinmetz had a long conversation one morning in the library, with the door half-closed, but apart from that he did not seem to engage with his guests. He had a courtly, bantering manner with Lucy that in another man Harriet might have read as flirtationâLucy was still very pretty, and Fowler would have seen, or noticed, little of her shrewish side. With Cecil, a recent convert to golf, he chatted about niblicks, mashies, and spoons. The children seemed to make no impression on him at all. Dr. Steinmetz took the fussing baby from Lucy one morning after breakfast and circled the dining room humming and muttering to her in German. He stopped next to his host, who was reading the newspaper.

“Hmmm?” queried Fowler Truscott when he looked up, and Dr. Steinmetz offered him the child. “Oh, oh, I couldn'tâ¦no, I think you're the man for the job. Carry on.” The remark stuck in Harriet's mind, and even more so the attitude of aversion. Men were not expected to be gifted in these matters: Cecil and Dr. Steinmetz were ex

ceptions to the rule. Still, there was something sorrowful in that moment, which Harriet had to resist. If she gave in to it she could not preserve the hope that she too might be blessed with a child.

What had seemed at first to be the understandable fatigue of a man who had been working under great pressure came, after several days of doing nothing more strenuous than lifting his glass and the newspaper, to suggest a chronic condition, perhaps illness, perhaps age. The least acceptable reflection was that her husband, during these months of their separation, had drifted away, or drifted back, back to the habits of mind and feeling that governed his life before courtship and marriage. A question presented itself to her for the first time: if a man does not marry until the age of fifty-three, would it not be sensible to conclude that he had some reservation about the state of matrimony, perhaps an aversion to it? Harriet had always managed to imagineâbecause Fowler had told her soâthat he had simply bided his time until the perfect woman came into his life. Now Harriet was caught short whenever Fowler Truscott paid tribute to his perfect wife. The compliment was delivered in a tone of utmost sincerity, and still it grated on her, and she had to force herself to maintain the smile, the expression, the mask of the perfect wife.

By the obvious measures, Harriet's house party was a success: her guests were well fed, no one fell ill or quarreled, and the predicted snowfall went elsewhere. The weather was clear and not too cold. If it held like this they would be able to skate on the pond on New Year's Eve. But if nothing had gone wrong, neither did Harriet take any great pleasure in her achievement. She found it absolutely necessary to get out of the house whenever she could, away from all this merrymaking.

The day after Christmas, after her restless night, she had gone out for a walk with her husband. After about fifteen minutes Fowler asked if she was ready to go homeâhead back to the fire was how he put it. No, she said, she really needed to stretch her legs, otherwise she would have no appetite for dinner. Well, said he, you'll know where to find me.

Harriet walked on, straight to the office. It had come to her last night, when she was thinking about Toma anyway, that she must invite him to dinner on New Year's Eve. Dr. Steinmetz would welcome the opportunity for fresh conversation: she was worried that he might find Lucy and Cecil a bit limited. She should have mentioned the party

when she had last seen him, but she had not been thinking clearly, and now the ink was frozen, not a pencil to be found.

The telephone sat on a table that had once supported Amos Bigelow's collection of catalogues. She knew that one turn of the crank would produce one ring, his signal. Why had she never dared to do this before? He answered on the fourth ring, just as she began to wonder what she would say if someone else picked up the phone down at the Experimental Site.

“Yes. Is that you, Stefan?” The voice, scratchy and blurred by a clicking like cicadas on a summer night, did not sound very much like Toma.

“Hello?”

“Who is this?”

“It is Harriet, Harriet Truscott.”

“Oh?” There was a flurry of the clicks, followed by what sounded like the word “Christmas.”

“And to you. Will you come down for New Year's Eve?”

“I can be there in twenty minutes.”

“No, not now, on New Year's Eve, at our house.”

“New Year's Eve. Yes.”

“At seven?”

“Seven o'clock. Yes.”

“Wellâ¦good-bye.”

She put the earpiece back on its brass cradle and then sat down because she felt faint. She had meant to tell him about the skating party and to apologize for her abrupt departure. It was so hard to hear anything; but that was not the matter. The bad connection had almost caused him to run down the mountain to meet her, which would have been an awkward misunderstanding, a misunderstanding that pursued her on her walk home.

She tried to reason her way through: Did they not meet almost every day in that office? Why should it be different on this day? But it was no use. She felt the difference in her bones, acknowledged it in her conscience. If she had not spoken so quickly?

She slowed her pace to let what might have been play itself out. He would arrive, in fifteen minutes, not twenty, ruddy and winded by his exertion. She would explain and he would smile and ask: Have I come in vain? And she would flush and reply: Yes, it was my mistake, but I

am glad to see you. She would wish she had something to give him, a plate of biscuits or that pretty box of chocolates Fowler had brought her, forgetting that she did not like marzipan. There would be a silence that she would attempt to fill, talking of this and that, and then she would be off, walking home as she was now, filled with the same uneasy excitement, the same dread of those lights ahead.

Â

W

HEN THE HOUSE PARTY

was in full swing, it was Dr. Steinmetz rather than her husband or Lucy who accompanied Harriet on these necessary outings. She chose different routes for the sake of variety. One day they visited the Experimental Site, and while Steinmetz conferred briefly with Piccolomini and the Swedish engineer, Harriet gazed around her at the transformation of the old mill, remembering Horatio and her father in the old days. She could look forward to telling Toma that she had seen his great wheel in action.

On another day, he on her old pony, she on the new mare, they rode out on a road beneath the mountain. Fingers of the afternoon sun pierced the cloud cover, and when one grazed the mountain, making an irresistible brilliance on the snow and cliffs, she looked up, shading her eyes with her hand, and asked if he must keep her in suspense: she longed to know what he had intimated in his letter.

“Does it have something to do with the mountain? Or did I imagine that?”

“It does, and much more. It would be best if I draw it for you. That would make clear everything. Shall we go back?”

The house was quiet, except for Caroline's complaint somewhere away in the staff wing. The others had gone off in the car with Fowler at the wheel.

“Where shall we sit? We can call for some tea.”

He chose the library for its desk. Harriet knelt to light the fire, and when she stood up, Steinmetz had helped himself to a glass of Fowler's whiskey.

“No tea for me, thank you. Will you take something?”

First she said no, then changed her mind, and Steinmetz poured sherry into a tumbler. They drank to each other's health, and she said how glad she was to have his friendship. They drank to friendship.

“Dear Doctor, we must get down to business soon, or I will not be able to follow a word you say.”

Harriet pulled a chair close to the desk so she could watch the swift sure strokes of his pen.

“That must be the mountain, and the river, andâ¦the railroad.” She named things as he drew them, and sometimes he labeled them.

“How do you spell âcanal'? Do I have it right?”

“It doesn't matter. You haven't lost me yet. And what is that?”

“That is the tower on top of Lightning Knob, as it will be when Mr. Peacock has finished his work.”

He began to draw lines that she could not make sense of, a dotted one encircling the Truscott pond, and broad, bold ones descending from Great Mountain.

“What are these?”

“Just a minute, my dear, and I am finished.”

The swooping lines were added at last, and some odd boxes that resembled nothing in nature or on any map she had ever seen.

“There. I think that is enough.”

“More than enough for me. I have lost the thread here.”

“Do you remember, when I came here first, we spoke about the grid, the universal electrical interconnection, and about the part that Mr. Peacock's turbine might play in harnessing the water of the high mountains?”

“Yes.”

“Good. And thanks partly to your help and fine hand Mr. Peacock has come far toward our goal on the Knob up there, an important work because there can be no great stride forward until the lightning has been tamed. It will undo our labor.”

“I think I follow you.”

“Excellent.”

“And what you have drawn here is another stride?”

“Yes. When the war ends there will be a tremendous demand for electrical power, and the grid will expand to include the people living beyond the cities. Little towns like Beecher's Bridge will have streetlights. Farmers beyond the towns will have lamps to read by, to run washing machines, and tractors, and radios.”

“Do you think so? I don't want a radio.”

“Mrs. Truscott, believe me, everyone will want these things.”

“Can they not have them?”

“They can have them, yes, but not until we fix the problems of supply and distribution.”

“And that is what you have drawn? The victory over⦔

“Supply and distribution, yes. What we see here is a piece of the puzzle.”

“Why a puzzle?”

“There is this difficulty with making electricity: if we make it now we must use it now. There is no place to put it away for later.”

“A battery?”

“Only for small amounts, very small, and it is expensive. The battery is not the answer.”

Harriet studied Steinmetz's page, wondering what she was missing.

“Suppose you had electricity here in this house.” Steinmetz dipped his pen and drew a house by the pond. “Where would the electricity come from?”

“Here.” Harriet tapped the Experimental Site.

“And when would you want to use your electric lamp?”

“In the evening.”

“And your neighbors?”

“They would want light in the evenings as well.”

“Yes. Everyone would want the same thing at the same time. But the river, you see, is running all the time, all day and all night.”

“As it should. Would you change that?”

“No, but that is a great inefficiency. In a city like New York, or Chicago, we have the streetcars that run on electricity during the day, and if we make the electricity cheaper at night, the factories will run their machinery at night, to save money. But in Beecher's Bridge you only want your light at night, perhaps very early in the morning. We cannot change that, and it is the same everywhere, in all the Beecher's Bridges of America. It is not efficient to run huge dynamos for only a few hours a day, and the grid depends on efficiency. That is its reason for being.”