The Lightning Keeper (19 page)

Read The Lightning Keeper Online

Authors: Starling Lawrence

Her angry comment that night had touched some nerve bared by the drink. He laughed in a way she did not recognize, then put his hands on her roughly. She thought he wanted sex, and she made clear that she was having none of it. She slapped his hands away and by accident hit him a glancing, backhand blow on his face. It was the first time she had ever refused him. It was the first time he had ever beaten her.

He hit her with his open hand and with his fist and with the stretcher ripped from a broken chair. He beat her after she stopped struggling or even trying to shield herself, and all without saying a word. No explanation or accusation, as if they both knew what must be done. He tore the shirt from her in an effort to keep her from running, then held her by the throat and slapped her breasts. I won't run, I won't run no more, she said. Go on and fuck me, Horatio, if that's what you want. I don't care. You hear? I don't care. He knocked her down, slamming her head to the floor, and that was the last she knew until she awoke in the dark, aching, her mouth full of blood, lying in her own soil. What had happened to her when she was unconscious? She did not know.

She resolved that all this would be forgotten: it would be as if nothing had happened. Things returned more or less to normal, and there was a kind of peace between them. But one thought remained: that she should, or might, kill him. She was amazed that such a thought could have occurred to her. It was three days later, when her lip was healing and the marks on her face all but vanished, that Toma first came to the mill.

She thought again about the priest, trying to remember his face, for she did not go to church very often. Horatio hated churches the way he hated bad grammar. They were both signs of ignorance, of weakness. I have had sinful thoughts, Father, about killing a man. Your husband? No, he's notâ¦And so the conversation, the confession,

would wander off into other matters that might concern the priest, or even God, but did not seem urgent to her. She could live with what had happened in the past. She knew her mother was safe and with God. She could even live with Horatio, or thought she could. But something had changed for her the day Toma came to call. And now he was back. Horatio had brought him back.

Horatio liked him, now, not at the beginning; that much was clear. Who else did Horatio like? Nobody.

She had never slept with any man other than Horatio, never kissed one. Her experience and his vigilance had burned that curiosity out of her. But now she was seized with a strong feeling that lay somewhere between love and regret. Regret for what? Something she had lost, or something she had never known? She had said those crazy things to him, made her confession to a man as much a stranger to her as the priest. Then he was gone. And reappeared now in this improbable way. What would she do to keep him? What would she not do?

There had been no time to think at first. She had sent one of the men to the pharmacist with her laundry money for the draught, saying, Wake him up if you have to. When they had got the laudanum into him and he drowsed off, only then did she dare cut the boot off and probe the wound for splinters of the bluish glass before binding it. The next day he slept still, and she washed him, cutting those ragged clothes away until he lay naked on the sheet. She rebandaged the foot, applying the herbs she had gone out to gather at dawn. Now she had time to think.

These thoughts had the terrible power of novelty. Here on her bed, where she had experienced the things that bound her soul, lay a man who might set her free. It was as simple as that. She did not stop to consider the paradox that her bonds had been invisible until a means of escape appeared; neither did she ask if her deliverer were willing.

Toma slept on, with only the rise and fall of his chest as a sign of life. In this heat there was no need to put the sheet back. Washing him was a task like washing the clothes in her tub: something that needed to be done. But because she had not covered him, this moment was suffused with a disquieting intimacy.

She had drawn many things: flowers, buildings, bits of Horatio's scrap, his hands, even his head as he sat in his armchair concentrating

on something. Never a figure drawing. But she had taken a drawing class in the libraryâit was there she had formed her nodding acquaintance with Harriet Bigelowâand had seen those books, so she knew something about the unclothed figure and its aesthetics, if only through the eyes of others.

He is beautiful, she thought. With her hands clasped in her lap, she struggled with the mystery of a new desire. Would it be different with him?

She made a mental inventory of the things Horatio had required of her for his pleasure, acts that had not grazed her imagination until now. That had been sin. But she would give him everything. He would not have to ask, much less compel, because she would know. That was the hidden gift of her sin, and for a moment she could almost forgive Horatio.

Horatio. She imagined Horatio's wrath were he to know her thoughts. How could she hide them from him? She could run away, but where? Or she could kill Horatio. Here was the thought that would drive her to the priest, and she raged at both of them, Horatio and the priest. How could what she felt for Toma have turned so quickly to its opposite? This was madness, as palpable as nausea or a rising fever. She drew the sheet up to cover everything but his face.

Nursing him, sleeping on the floor, the heat. She was worn out. But worst of all was his indifference. She saw no sign that he had any feeling for her other than an awkward gratitude. If anything, he avoided her eye. He seemed angry himself, muttering at the weeping wound in his foot, muttering in his sleep, which disturbed hers and Horatio's too. The only time he seemed happy was when the white woman came to call. After that, even his courtesy became bitter to her, and she hated them all: Horatio, the priest, and now Toma.

Her back was to the door and she did not see it open; neither did she hear it over the hiss of the wheel and the clatter of the paddles. But the sweat was running down her arm now, and when she half turned to find a rag, she saw him out of the corner of her eye. He had a length of two-by-four under his arm as a crutch.

“Didn't I tell you not to be walking around.”

“I had to get to the privy.”

“This ain't the privy. You didn't see the sign on the door?”

“No.”

“It says Keep Out. I tried to keep it simple.” His smile broadened. She glanced down at herself, following the momentary flicker of his eyes. The batiste of her camisole was plastered to her chest and the blue flowers of her wrap were the poor sentinels of her modesty. She might as well be naked. She brought one arm up across her breasts. She could smell her own sharp odor. He could probably smell it from where he stood. He was not smiling now.

“I am sorry. I heard your machinery and I did not stop to think. Will I disturb you if I am looking at it?”

“Look all you want.”

“Thank you. You will show me how it works?”

She should have told him to turn his back so she could cover herself, but it was done, whatever damage could be done by looking. From his appraisal of herâthe movement of his eyes seemed almost accidentalâshe knew that he was not shocked, knew that he had had other women. It did not matter now. He would not look at her again. There was a hopeless quality to her rage: she wanted at least to be noticed.

She eased the clutch lever forward. The paddles grew still and the wheel, now free, spun faster. He bent over it awkwardly, trying to keep his foot clear of the spray. She began to fish the clothes out of the rinse water.

“You shut that thing off when you're finished. No need to be wasting my water.”

They had no further conversation. She put the clothes through the wringer, turned once because she thought he had said something, and saw that he was talking to himself. When she was done with the ironing he was still fussing with the wheel, soaked to the skin, and the bandage on his foot looked like an old mop.

“Come,” she said as she shut off the tap. She lifted him to his feet and saw that the bolt of pine lay beyond her reach. He was as meek as a child when she draped his arm around her neck and led him away to the sickbed.

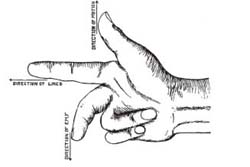

Figure 21

Fig. 21 shows a method by which a wire carrying a current and free to move may be arranged. This is a most important experiment, and, if possible, should be performed by everyone interested in the study of electricity. The experiment shown in Fig. 21 is the fundamental experiment showing why it is that a motor will operate. By reversing the experiment shown in Fig. 21, and by causing the wire to move across the lines of magnetic force, it is possible to generate current in the wire. This is also a fundamental experiment, for it shows in the simplest possible manner how mechanical power can be transformed into electrical power, or how a dynamo works.

Figure 22

The relations that exist between the direction of motion of the wire, the direction of lines of force and the direction of the current in the wire when moved by hand or by mechanical force, is most easily remembered by extending the thumb, first and second finger of the right hand at right angles to each other, as shown in Fig. 22.

âPractical Electricity,

sixth edition, 1911

Toma's dream was so pleasant that he awoke laughing. He had constructed a machine that caused all of Mr. Bigelow's wheels to be fabricated in the twinkling of an eye, and when Harriet Bigelow called out his name in those flute tones of the thrush that sings after the rain, he answered her with a question: Which of us shall cross, for see how the river has fallen? She made no answer but disengaged herself, laughing, from the arm of Senator Truscott and then walked across the water without wetting the hem of her skirt.

There was such promise hereâinterrupted by the inconvenience of his wakingâthat he tried to reimmerse himself in the details of his dream. What was the exact expression on her face as she passed over the water? Did she step upon stones in the shallows, or was she borne up by the water itself? What was the working of his machine?

Dawn bloomed through the high windows of the monitor and Toma puzzled for a moment over the particular quality of this light. The air was pleasantly cool and the panes of glass glistened. The weather had changed, but there could not have been so much rain or else he would have woken sooner.

He could not capture the creature of his dreamâshe was both less and more than the woman who had sat on this bedâbut he was glad to be awake and alive. He stretched extravagantly, his pent energies coursing to the extremities with an almost epileptic violence, and the yawn was a kind of ecstasy. When he opened his eyes, his gaze fastened upon

a five-bladed fan in the shadows above the windows. He blinked, then squinted. Those skeins of cobweb attesting to the fan's disuse suggested the work of a gigantic spider, orâ¦He held his breath until the thought should complete itself.

A movement of the calico curtain interrupted this waking dream that had enveloped the earlier one. Dreams within dreams. Olivia noted the strange expression on his face.

“Are you well?”

“Very well, and today will be a special day.”

“I brought you coffee. Heard you laughing and knew you'd done sleeping. Here. Mind you keep your foot up.”

He took the burning enamel mug from her hand, then laughed, almost scalding himself as he did so.

“What?”

“I believe you are trying to make yourself look ugly. Can't you smile?”

“Why should I smile?” Her expression became more resolutely severe.

“Oh, because the heat has broken, or because my foot is getting better, or just because I ask it of you. What have you done with your hair?”

The slight motion of her head sent a shudder through those countless spirals, a feral message like the bristling of a dog. “Nothing. I washed it and tied it up to be out of my way.”

“Yes. There is copper in it that I have not seen before.”

“Red, you mean. When I see that I want to cut it all off.”

“You must not do that. Come closer?”

She did as he asked, bent down to him. Did he wish to say something to her in confidence? No, only to look closely at the band of plaited silk that bound her hair, that little rainbow that she had fashioned from the spooled thread on the shop wall. He held up to her gaze the silk cross, plaited of fine colored ribbon, that hung at his neck. As if she hadn't noticed.

She said nothing. Of course it had been for him, and what was the use of it if he did not notice? But now that he had seen what he was supposed to see, she felt foolish.

He was sorry that she could not share this feeling, the sense of possibility and fruition glimpsed in the instant of his dream, which was

still expanding obscurely within him; and even though he lay perfectly motionless on the bed, he had the odd sensation of being full to bursting with this immanence, of having to concentrate on each breath as if it might be his last.

He thought of the things he would need, for all of which he was dependent on Olivia's goodwill. She must take his telegram to the depot and leave word at the works for Miss Bigelow to send him a particular catalogue, and for Mr. Washington to spare him some time at the end of the afternoon. She agreed readily, and he calculated that she would be gone for a good two hours on these and other errands. Two hours in thrall to this glowing surge was a lifetime: if he survived it he would have mastered the machine in all but its physical execution.

He must be calm in order to work, and when he heard the door close behind her, Toma spent the first five minutes of his two hours trying to slow the racing of his mind and heart. He set his undertaking against Edison's vast achievement and the incandescent musings of Nikola Tesla, his fellow Serb, who would surely scorn the expenditure of precious thought to the end of manufacturing a few iron wheels. He had, with his own eyes, seen the working of Tesla's coil, wherein currents, alternating to the millionth of a second, strove and resonated with each other, magnifying the mystery of the universe, channeling it through the very body of the inventor to produce an unearthly glow in the sealed glass tube clutched in Tesla's hand.

Tesla had talked of the things that could be achieved with his inventionâthe coilâand by harnessing electrical energy to meet human needs and desires as yet unglimpsed. But it all began with an idea, Toma was quite sure, not with some specific physical challengeâan idea that would quite literally light the way into the future. Judged from the perspective of the task, the making of wheels, his own putative solution was no more than the labor of a mechanician: the water would move a dynamo whose mirror image, the motor, would move the air, and the wheels would pour forth from the furnace mouth. But he had been guided to this electro-mechanical linkage by an idea, and that idea was most simply and thrillingly expressed in the vision of Harriet Bigelow crossing the water toward him. An idea could move the world and anything in it. When he closed his eyes, the fan above him began to turn.

JOHN STEPHENSON 121 WORTH NEW YORK CITY 10 AUGUST 1914 PLEASE SEND BROKEN DYNAMO BODY SHOP STOREROOM AND VOLTMETER STOP WILL PAY FREIGHT STOP FOOT MENDS SLOWLY STOP PEACOCK

c/o Wright's General Store

Beecher's Bridge, Connecticut

United States of America

August 11, 1914

Auberon Harwell, Esq.

The Grand Hotel

Cetinje

Montenegro

My dear Harwell:

I write to you in great excitement.

I was in a very bad way when your letter arrived. I had received a wound in my foot, and also I had heard the news of my homeland. It seemed that the world and my fate conspired to bury me alive in this place so far from my people. But your words recalled me to myself and what I must do.

You would laugh to see me: I am like my father with his wooden leg. Not a real one, but one I made only this morning, with a block under my heel so that I can put no weight on the wound. It is like a very short stilt, and I am lopsided. My nurse could not contain her laughter even as she tried to be angry with me. I do not mind her laughing, for it is pleasant to hear, and in any case I can walk.

And you, my dear English, would laugh also to see what object my genius fastens on, but perhaps a bitter laugh. What a strange education you have given me: Homer for the exercise of the soul; a bit of your peculiar Bible to temper my brutish religion; Macaulay for style and rhetoric; and that crabbed work of science to point the way to my future. You hated that last book because you could not understand it, and you persevered only out of love for my mother, I think. It must have been so, for I heard what you said under your breath, words that were never found in my dictionary. “Sodomite,” you called him, poor Professor Drinker, and said that because of his book you must banish all red books from your library. Do you remember telling me that you could not approve of a book that caused you to question your own intelligence?

It was like having a blind man as a guide to an extraordinary landscape, but I am grateful for your trouble, and now more so than ever. I am in mind of something you once said and have probably forgot. It was not long after we had made the dam so that our neighbor's cattle might drink from our stream. And the water when it went through the channel had a great strength to it, causing, from time to time, a little whirlpool or vortex, like a man with his pipe blowing smoke rings. Later that night I was asking you questions about the vortex, puzzling over how one might measure the force of the water there or predict its course in the stream. You tired of these questions that could not be answered, unless perhaps by Professor Drinker, and said this: “When a leaf or a bit of wood is caught in the whirlpool it is real to me for that moment because I can see what happens, and it almost makes sense. But you, Toma, can hold the vortex in your mind without such aid, would make it stand still so that you can measure it, and one day you will be able to summon such things without having seen them at all, and they will be as real to you as the table here or this spoon.”

Your prophecy has come to pass. There is a curious device in this place where I am living, a waterwheel fashioned by my host. It is driven not by the river current but by a narrow jet of water under a head of 160 feet. Although the pressure is terrific, the actual flow or expenditure of water is modest: a most ingenious and efficient thing. I have experimented with the positioning of the nozzle and the delivery of water to the blades or cups, making such calculations as are possible without any instruments at all, and trying to fix, first in my imagination and then in the nozzle and the wheel, the perfect flow of water to the blades and its unimpeded escape.

There is an economy to this device, and of all things necessary to the ironworks just now, water is the most scarce. Not only will this wheel produce a mechanical effect, but also an electrical potential, and if I can adapt this source to my task of iron making I shall have done something clever. Yes, it is only a trick, or might seem so, and such wheels have been used for some years in the great mountains of the west, where a simple sluiceway can deliver hundreds of feet of head to power machinery or make electricity. But I can tell you there is something about this wheel that will not let me rest, something that defies the mind's grasp, and at night I see in my dreaming the vortexâperfect but for the friction and gravityâformed by the water jet as it is shaped by the wheel's vanes. There is perfection in this, somewhere, could I but see it and seize it, and I am haunted by it, by the turning of perfect wheels.

Do you knowâof course you do notâthat the connection between mechani

cal motion and electrical impulseâone producing the other, or vice versaâarises from a circularity similar to what you observed with the leaf in the vortex? Put a current through a wire and you produce concentric rings of a magnetic field circling that wire: magic indeed. Wind that wire into a coilâit is called a helix, but vortex would mean much the sameâand you have made a magnet, with poles, north and south, at either end of the coil. Or wind your wire on an iron core and place it between the poles of a large magnet, and you have either a dynamo to make electricity or a motor to produce mechanical rotation. In either case, motion or electricity is produced as these little circular fields around the core wires, acting in concert, react to the field of the embracing magnet. Force the core to revolve in that field and you will produce electricity; or run a current through the same coreâreverse your processâand you will produce mechanical rotation.

There is a beautiful simplicity in all this. Perhaps you will take my word, for I am speaking of a mystery that no one truly understands. But if you were here in Connecticut I could show you the workings I have described and you would at least appreciate the symmetries. The helix and the vortex, the flow of water or electricityâ¦perhaps it is all one if properly understood.

Such elusive perfection, such fertile mystery viewed from the small space of the mind. I have fallen into a madness that is like the madness of love, and it is hard to think about anything else. It

is

the madness of love, for, as I have written you before, I must have this woman, Harriet Bigelow, who is the mover of my labors.

I shall do what I can, and I shall write to you of my success if that is to be. My thoughts are with you in your own great undertaking: may any daughter have the grace and courage of her mother, and may any son grow tall and be in all things a proper English.

My affectionate regards to you both,

Toma

PS: I have made such a compression of my thoughts in this letter that when I read it over I scarcely understand my own words. And I have left out something that is puzzling to me, something that I must understand. My host, the maker of the wheel, has a black skin. He must know something of my feelings for Miss Bigelow, for he mocks me, and himself, by saying that we are the same: not brothers, but alike. We are not, and can never be, equal to good people like the Bigelows. He is a proud, bitter man who has thought much on these things. You once told me that your family and Lydia's were not of the same circle, which was

why you spoke the same language in different ways. Does this mean that you and Lydia cannot live in England? As you know well, Aliye could not live with my people, nor I with hers. It was only when I came away from Montenegro that I saw her as I see her now. What does this mean for my present hope? Here is another subject in which you can instruct me.

T

OMA SAT AT THE BENCH

with his head in his hands, the Cleveland Armature Works manual open before him. He turned back to the first page of Chapter XVI: “Diseases of Dynamos and Motors: their symptoms and how to cure them.” On the bench beside the book lay the yellowed enamel of the Weston voltmeter with its obdurate and unmoving pointer. It had been a long day. It would be a long night.