The Lightning Keeper (17 page)

Read The Lightning Keeper Online

Authors: Starling Lawrence

Mr. Brown, dour fellow that he was, had still some sense of ceremony about these few minutes. The last of the slag was tapped and run off. As it cooled into volutes and spirals of rough glass, he inspected those forms and hues as would a priest the entrails of the sacrifice. When the iron itself was tapped, he attended to the flickering spectrum, read there the traces of those elements that would determine the properties of this particular batch. He nodded his head, satisfied that disaster had been averted.

Toma stood apart from the crew and the townspeople with his back to a white pine. He couldn't hear much over the wheeze of the bellows, but he could see how the onlookers were enveloped in a tide of happiness: backs slapped, hands shaken, pint bottles passed covertly from one pocket to another. This should have been his celebration too, but in the rush of heat and light from the breached furnace he saw only war and death, for this morning, on his way to the works, he had passed by the telegraph office in the depot to hear the news. Sometime in the night the Austrian troops had crossed the border into the Kingdom of Serbia, implementing Plan Yellow, the general mobilization that Harwell had told him about long ago, and by now, for all he knew, they might be at the walls of Belgrade.

He was thinking, then, not of wheels and inventories but of what he must do. Somewhere, back across the sea, boys younger than he were marching through the night or peering over some parapet, imagining the might of Austria that the dawn would reveal. It was his war. Was there not an invisible thread held in the same hand with which Aliye had killed herself, turning first around his mother and the Austrian captain he had slain and now around all those young men yet to die? Harwell, who had brought him through the valley of death on their escape from the Sand ak, from the Austrians, had told him, on the basis of certain and secret knowledge, that the tinderbox of the Balkans, had wanted only the one spark, and now, six years later, another Serb had killed his Austrian.

ak, from the Austrians, had told him, on the basis of certain and secret knowledge, that the tinderbox of the Balkans, had wanted only the one spark, and now, six years later, another Serb had killed his Austrian.

Surrounded by his ghosts, Toma stared unseeing at the celebration and was surprised by a touch on his arm. Harriet had come to be with him, and stood with her back to his tree. Was she too a ghost? Did she hold in her hand the other end of Aliye's thread?

Feeling his gaze on her, she turned to him. He took her hand and she let him do it, though it was not yet dark.

“I am sorry I cannot stay, but I must take my father home. He has been worrying himself, and this excitement is draining him. But perhaps I could⦔

“Yes,” he said, and saw that it was a mistake to anticipate her thought, for with no visible motion she withdrew from him.

“What I meant, what I would ask, is if you could use your influence on this celebration. See how those dreadful bottles are passed around. Remind them, please, that we must work tomorrow.”

In spite of her tone, Harriet walked away from him with such a lingering step that he thought she had more to say, or would turn to look back. But she did neither of these; only her gait betrayed her indecision.

When she had vanished down the dark tunnel of the road to the works with her father, Toma relaxed his shoulders, then stretched. He still felt the effects of his violent labor, but the deep ache in his bones was reassuring to him. He wandered away from the tree, glad for the company of living men, and instead of following his instructions found himself partaking of those offered bottles, the rough whiskey another defense against ghosts and regret.

There was no general drunkenness this eveningâthe furnace men were not so dissolute as Harriet fearedâand Toma felt only contentment as he moved away from the furnace to make water. The stars were bright and near in the black sky, and they seemed almost to flicker at him, for at each resounding groan of the bellows, a column of flame and sparking cinders flew up from the stack and bleached away the firmament.

The slag pile was as old as the furnace, and so concealed in brambles and the eager vines of bindweed that its exact extent could not be determined. In the clearing and rehabilitation of furnace number 3 the contours of the heap had been pushed back, and the glassy chunks,

rounded and softened by time, were broken into new forms by rough handling. It was one of these, a dagger of cobalt shot with green streaks, that Toma now stepped on. It slid through the sole of his boot and on through the foot.

Toma fell backward onto the slag, receiving other wounds to his back and scalp. When he was foundâand he was lucky to be heard between wheezes of the bellowsâit was not immediately apparent what had happened, for the pain so bound his tongue that he was not coherent. Looks like he's been shot, said someone, and Horatio was called for.

“Jesus Christ,” said Horatio, “will you look at that. Don't touch it!” The flaming light of the furnace caught the tip of the shard where it had split the tongue of the boot and cut the laces. Toma had recovered his senses somewhat and tried to rise, but Horatio held him down.

“You stand on that and you're going to feel a whole lot worse.”

“The hotelâ¦Mr. Wright will help me.”

“And how is he going to help you, except maybe help you lose the whole damned foot, and then you won't be any use at all.” Ignoring Toma's protests, Horatio detailed two burly furnace men to carry the injured man down to the silk mill.

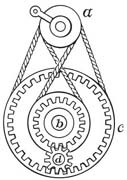

A planetary motion. Revolution of a pinion around its own center and also around the common center of two externally centered gears. a, driving pulley with cross band to gear pulley b, and direct band to gear pulley c. The differential motion revolves the pinion D around its own axis and around its external axis b.

Weeping wounds

Although clean lint is the dressing of choice for any wound, bog moss may be used if properly prepared. Moss should be dried, picked clean, and thoroughly steamed or passed through a solution of corrosive sublimate. When dryâa sterile mangle may be usedâmoss may be stored for future use. Do not allow moss to touch the wound, but use it as a thick layer between inner and outer windings of muslin, where it will readily absorb any suppuration. Change dressing when saturated or crusted. Muslin may be boiled for 10 minutes and dried. Do not reuse moss. See page 47 for Comfey Leaf Ointment, and page 59 for various Spermaceti Salves.

âfrom

Ransome's Herbal Remedies, 1867

The Royal Victory Hotel

Belgrade, Serbia

18 July 1914

Thomas Peacock

c/o Bigelow

Iron Hill

Beecher's Bridge, Connecticut

United States of America

My Dear Toma:

As Chapman puts it:

“O 'tis a most praise-worthy thing when messengers can tell

(Besides their messages) such things as fit th' occasion well.”

In the evenings, having nothing better to do, I distract myself by attempting my own translation of Homer. I am satisfied that my rendering is an improvement on Chapman's accuracy, but I do not have his ear, his musical gift, and so I yield to him here.

Lydia has not been able to travel with me to Belgrade because of her confinement, so I am a bachelor again, though soon to be a father. Thank God she is not in this place, At least she was able to forward your letter of 20 May. I am certain she has already written you with news of your father's and your sister's health.

Hearing from you makes me long for simpler times, but perhaps the attraction of the past is that it is over, and we can make of it what we will. Uncertainty often seems more terrible than any known grief or pain, and this moment in Belgrade answers that description.

You will have read in the papers how Gavrilo Princip, ineptitude notwithstanding, managed to dispatch the Archduke Ferdinand to his eternal reward.

What you may not have heard or read is the confession wrung out of Princip by his captors, the details of the investigation by the Austrian authorities, and the particulars of Austria's summary demands on Serbia. It will come as no surprise to you that the assassins were connected with the Black Hand, so called, and that their aim was to free Bosnia from the oppression of Austrian annexationâa blow struck to further the cause of Greater Serbia. The Serbian government would like to pass all this off as the work of young radicals who have no sanction or support, official or otherwise. But their protestations of innocence are undermined by certain details in the confession, and more significantly by the evidence of the unexploded bombs in possession of the conspirators: they come from the Royal Serbian Arsenal at Kragujevac, this provenance clearly stamped on each device.

I have now a confession to make that will qualify me as a source of advice on the political situation here as it concerns your future. You will remember the occasion on which I made a visit, uninvited, to your quarters in the Hermit's Cave at Stupa Vasiljeva. It was your mother's anxiety over your comings and goings late at night that prompted my mission, for she knew you were too good a hunter to come back night after night empty-handed. When I discovered the secret of your cave I could not bring myself to tell your mother the truth, for she had already lost two sons and you were, perhaps in all innocence, simply honoring your brother by providing a decent burial for his remains. I held my tongue and hoped that I had done no wrong.

But there were other items there besides the body, and I refer to those explosive devices for which he sacrificed his life, the same bombs that Princip carried, I should venture, but quite certainly from the same source at Kragujevac. I have a precise memory of the coat of arms stamped on the metal.

I am not going to argue politics with you, even though the bombs in that case were intended for use against Prince Nikola, now King of Montenegro and my esteemed employer. A king has many friends and many enemies, and must take care for his own safety. But it is your safety that concerns me closely as war

gathers so palpably in the Balkans and you sit in a foreign land pondering your course of action. Do not, I beg you, be so foolishly brave as to entertain the thought of returning to answer this crisis of arms. You are still persona non grata in Cetinje, however much the king's courtiers and ministers may approve of your conduct on personal grounds. Your execution of the odious Captain Schellenberg was very nearly a casus belli, and although the Austrians took no punitive military action, they did cut off the subsidy for a certain timeâa most serious step in the king's view. And the Schellenberg incident necessarily reminded the government in Cetinje of your brother's complicity in the bomb plot of 1907, that old stain on the family honor. Needless to say, should you fall into the Austrians' hands you can expect no quarter.

I invoke the memory of your mother in urging you to be sensible: she gave her life to get you out of the circle of violence and retribution that is now about to engulf all of Europe, and you must do what she required of you. There is nothing you can achieve here except the losing of your life.

As for myself, I feel no heightened sense of urgency or mortality. There are strong rumors of an imminent Austrian mobilization, and now that they have their excuse, I suppose we shall not have to wait very long to find out what will happen. In the meantime, the youth of Serbia, clothed in finery and ignorance, parade in the streets of Belgrade and are rewarded by maidens who stuff flowers into their rifle bores, and no one except myself perceives any irony in this. They will discover soon enough what war is, and whether flowers have any efficacy against the Austrian artillery. The government, of course, feels no need to demonstrate its heroism, and so to a man they have retreated to Nish, out of harm's way. This withdrawal leaves me, as the Montenegrin trade representative, quite underemployed, and as soon as the ink is dry on this letter I shall depart for Cetinje, there to await the arrival of the presumed son and heir. To what, you may well ask.

Lydia, I know, joins me in sending you warm wishes and prayers for your safety.

Yours, etc.

Auberon Harwell

Toma read the letter twice, wondering, each time, at its swift passage from Belgrade to New York to Beecher's Bridge. Even in the shadow of war, this small miracle. He smiled, imagining Harwell's irritation at another small miracle and at the failure of his prophecy. For the war had started, and despite the terrible rain of the Austrian artillery bombardment, the walls of Belgrade still stood; the flower-spangled defenders, wielding a few old cannons, had turned back the Austrian flotilla with great loss of life, and it was said that not a single Austrian soldier had set foot upon the Serbian bank of the Danube.

He thought about the letter, about what he must do, and his hand went to the silken cross around his neck. Harwell had given him that, and his mother had given it to Harwell. Why? A sign then of something, surely, and a sign of something else now. His eyes roamed the high shadows above the calico curtain and, finding nothing but cobwebs there, came to rest on his elevated foot and the field of snowy linen. His face contracted and darkened as he contemplated this obstacle to his will. Here was his answer and Harwell's reassurance: What use was a cripple when it came to fighting? The foot throbbed in response to his savage thought, and to the despair of his perception was added a drip of irony and the suspicion of cowardice. Had not his father prevailed over his enemies with his shattered leg? Had he not freed himself from the fallen rock with his own

hanjar

and bound the stump? Had he not told this tale to his sons with the evidence of those severed and impaled heads? Toma imagined that he bore yet the imprint of that terrible hand in the flesh of his shoulder: there could be no turning away from that past, or from the future.

He eased himself to the side of the bed, moving the foot last of all. He would stand up, take a few steps, and then think again, on the basis of this experiment, about what must be done. Everything was accomplished soundlessly until he put weight upon his right foot. He did not cry out, but the sound of his falling was unmistakable, even over the murmur of the river. Olivia had been folding laundry at the far end of the mill. When she found him he was unconscious.

Â

T

HE ROAD, BUILT FOR

the slow traffic of carts and drays and long since abandoned to the occasional pedestrian, was a challenge to the Packard and to Harriet Bigelow's confidence in herself. The saplings of the beech wood pressed in from both sides; in that pleasantly dappled, green-gold light, she had trouble gauging the depth of field before her, and the long lateral beech whips, seeking the light of the old roadway, were upon her before she could raise her arm. One of them, deflected off the post of the windscreen, had struck her face, and she was certain it had left a mark. When she flinched at the next grazing of the branches, and shielded her face with her hand, the wheel was jerked from her grasp by a loose boulder and the Packard stalled.

She resented the cargo on the seat behind her and felt foolish for having taken possession of it in such an impulsive way. At the same time, she was anxious for the safety of the portraitâan image of a woman, perhaps a saintâfor she knew it was precious to him. Perhaps she should find a frame for it. Perhaps that would seem too familiar a gesture.

The eyes had given her such a shock in the general store when she stopped there on the way to the works. She knew nothing of Toma's accident, and had enjoyed a late breakfast with her father, during which they offered a toast to the success of furnace number 3 with their teacups. She had stopped by Mr. Wright's with her list, asking that the delivery be made after noon, when Mrs. Evans would be finished with her cleaning, and she left an order for the ice man, who kept a notoriously erratic schedule. There was the portrait, askew and staring at her from the back wall, one corner propped on a bag of green coffee, the other on the collapsed mound of his belongings.

“Why is that thing over there?” she demanded rather sharply.

Mr. Wright, who paid superficial attention to his customers or to his lodgers upstairs unless they were in arrears on their accounts, had difficulty in locating the object of Harriet's concern. “I beg your pardon, Miss Bigelow?”

“Where is Mr. Peacock? And what are his clothes and that portrait doing here?”

“Ah, yes, Mr. Peacock. Well, since he won't be using that room for a while, I says to myself: Might as well rent it out to another fella as argue with him over the rent.”

“Has he gone, then? And why?”

“Not gone, no. Cut up his foot pretty bad, and the nigger sends word that he'll pick up them things later. That woman of his will look after him, meaning Peacock, down below until he mends up.”

Harriet's tone was so clipped that Mr. Wright might have imagined she was annoyed with Peacock for being so careless. “I shall save Mr. Washington the trip if you'll put those things in the automobile for me now. And we are nearly out of ice, so please locate Mr. Beckley, if you can, and alert him.”

For two days Harriet debated her course of action, and her cargo fermented in the sun beating down on the Packard, on Beecher's Bridge, and on the dwindling Buttermilk. She tried not to inquire too often after Toma's recovery, and her discretion was matched by the taciturn Horatio, who disclosed only that Toma was in pain and that he would recover. But on the second day Horatio knocked at her door and asked did she want him to take those things in the car.

“Thank you, no, Mr. Washington. I thought I'd bring them myself, and visit with him for a few minutes.”

Horatio said nothing and made no motion to leave, as if he were waiting for her to reconsider.

“Has the doctor seen him?”

“No.”

“But you said he was in pain.”

“Pain doesn't kill a man, and in my experience, Doc Spellman is hasty with the knife. Olivia tends to him. She knows these things.”

She stared at him, trying to read his thoughts and betray none of her own.

“Tomorrow, then. Perhaps in the afternoon the heat will have broken.” She turned back to the page of her ledger.

Â

T

OMORROW CAME AND THE

heat did not break, and now she was staring at the eroded gravel of the incline where the road approached the old silk mill from downriver. The turn off the main road was just a few hundred yards beyond the Truscott drive, but what a distance this dank, choked slope was from the clipped lawn rising to the senator's house, then subsiding to the lake she imagined to be paved with golf balls. Not

very long ago the thought of the senator and those golf balls would have provoked a smile: all that energy focused upon such silliness. But she had no fond thoughts for the senator today, and had driven past the stone gateposts without so much as a glance at the white house four square on the rise. It had been so much simpler before he had expressed his feelings for her. Why was that? She knew perfectly well what was on his mind, and had Mrs. Evans to remind her in case she forgot. But all was changed now, and though she did not know exactly what she felt for him, the situation between them no longer reflected her wishes or responded to her will. All the same, she knew that Fowler Truscott would not approve of this visit any more than her father, and she hoped that her car had not been seen on the road.

Harriet ended up walking to the silk mill. If she had made a determined run at those ruts she might have forced the Packard to the top of the hill, but caution lightened her foot on the accelerator. Although the rise was not steep, the driving wheels found sand beneath the gravel and the balding treads shot a hail of pebbles into the beech wood as the car began to slow. Too late she found her courage; the engine made a tremendous roar, but the Packard lost all traction and she panicked, turning the steering wheel to the right, where her path lay. She was traveling backward now, losing ground and altitude. The angle of the tires opened the way to disaster, and she ended up on a diagonal across the road with a beech trunk wedged between the tire and fender. The Packard, after a clarion backfire, stalled in this ignominious posture. She sat very still with her hands gripping the wheel. The lever of the spark was in the starting position, eleven o'clock: she must have knocked it with her wrist in the effort to keep the car on the road.