The Lightning Keeper (13 page)

Read The Lightning Keeper Online

Authors: Starling Lawrence

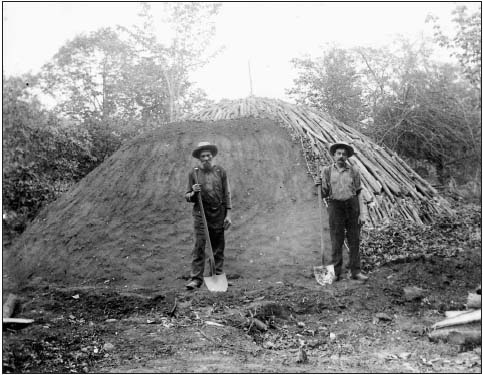

Making charcoal on Great Mountain

In the weeks following the arrival of Stephenson's letter, the Bigelow works came to life in a way that gave Amos Bigelow a sharp and peculiar pleasure, mixed with sadness. He remembered those glorious months, punctuated by ceremonial firings of the Bigelow Rifle, when triple shifts of workmen kept the furnaces going full blast night and day to manufacture the cannon barrels that were to be the salvation of the Union. His father, in that prime of his life, seemed not to sleep at all, and the furnaces were pillars of smoke by day and pillars of fire by night whose soaring sparks illuminated every corner of Beecher's Bridge like an endless Fourth of July.

The biblical allusion to those pillars was fixed in young Amos's mind by the sermon of the Congregational minister, delivered on the town green to all who would come, wherein he yielded to patriotic sentiment and announced that it would be more pleasing to God for this work to continue through all seasons of the year until His victory was won, through fire and flood if need be, and even on the day of rest. The priest of the other church could not be seen to be less patriotic than a Protestant, and he too found divine sanction for breaking the Sabbath. It is a curious fact, and testimony to Aaron Bigelow's powers of persuasion, that the monument on the green, erected on the very spot where this divine dispensation was announced, mentions but three casualties of the Civil War, and after 1862 not a single man from Beecher's Bridge was conscripted into the Union Army.

Harriet Bigelow knew that such a mood of celebration was premature, for the contract had not been signed. And yet she too had a stake in this new enterprise that gripped the ironworks and the town and every soul in it. How could she not respond to the happiness, the almost childlike happiness, of her father? He seemed suddenly a much younger man, not lost in his catalogues and daydreams now, but engrossed in the daily requirements and crises of the preparations: 2,280 spoked wheels for the 285 carriages at three and a quarter hundredweight of iron eachâat least they were lighter than the solid wheels needed for a railroad car. Here was a task that even the cannon maker would have relished, the grandfather she had never known, and on one occasion she saw her father pause in front of that now odious photograph and square his shoulders.

From early morning until evening she was tethered to her desk, the comfortable rhythm of her life as distant as a dream. Her mornings at the gymnasium, the Tuesday evening Temperance gatherings and the Thursday afternoon reading and discussion group of the Chautauqua Circle were counted among her sacrifices; in her garden the lettuces struggled against rampant chickweed and crabgrass, coming to the table as thin and pale as if they had been grown under pots, like French asparagus. The boy she had hired to help Mrs. Evans had no talent or understanding beyond the chore of turning the compost heap. She thought of the evening in May when Toma had helped her thin the young beets and turnips, and at his suggestion she had made a dinner of the thinnings, blanched briefly and mixed with maccheroni, butter, parsley, spring onions, and hard Italian cheese. It was as if they were again in Naples, and even her father had approved of the feast, a celebration of spring. On another occasion, when the frost was gone for good, they had set out the tomato plants together, he burying the roots and laying the first few inches of stem in a horizontal trench, she tying the tops to strong stakes with the strips of old linen that she saved from one year to the next for this purpose. She remembered the perfume of bruised tomato leaves and the dew of golden oil on her hands. They told the names of every plant in the garden, she in her language and he in his, and laughed when they came to one that neither of them knew.

She missed his help now that he was gone. Where had he spent that night, and all the ones after that? When he did not appear at

breakfast the next morning she went again to the carriage house and found the room swept bare except for the envelope on the table.

She saw more of Toma now than she had when he was living under her roof. He was polite, prompt, attentive, and, she thought, incredibly well informed on the arcana of iron production and metallurgy. But something about him was different. Together they sorted through the inventories and potential availability of ore, pig iron, acceptable scrap, charcoal, and limestone. In the brutal heat of early July she drew a crude map on the back of an envelope and sent him up onto the mountain to make an accurate count of the cords of seasoning hardwood to be stacked, covered with dirt, and fired. It would be a dangerous undertaking because of the heat and drought of the season, and difficult because the wood itself was not fully dry. But it would be cheaper than buying the charcoal from a supplier.

Together they made calculations of the output of the Bigelow Iron Company, under optimum conditions and under the assumption that the entire production would be directed to the cast wheels, at the expense of all wrought-iron articles and, in all likelihood, to the aggravation of some customers of long standing. Harriet had charge of the column of figures that yielded the number of tons of cast iron the plant could make in a twenty-four-hour period. This number was reduced somewhat to allow for spillage, defective castings, and the weight of metal lost in the grinding and finishing process. Then she divided by the weight of the finished wheel and multiplied, prudently and piously, by six in order to get the weekly production figure.

Toma had the easier task: he knew the number of wheels required, and the date given by Stephenson as the cut-off, and he had simply to divide the wheels by the number of weeks from start-upâa few days henceâto cut-off, and hope that the number at the bottom of his paper matched the number at the bottom of Harriet's.

A mood of playfulness overtook them, a counterweight to the solemnity of their reckoning. “I want to see your number,” he said, holding the paper to his chest.

“You must show me yours.”

“In your country, unlike mine, the lady must always be first, is that not so?”

“In the drawing room, yes, and at the table, or getting into a carriage.

But where there is danger, or where strength and clear thinking is required, the man must show the way. Do you not agree?” She leaned close to him, as if she were debating an impulse to kiss him, and at the last moment drew back, laughing, having snatched the paper from his hand.

Her triumph was momentary: he could see from the sag in her shoulders that the game was over. She put the two papers side by side so that he could see how many wheels or weeks had to be made up, accommodated by new calculations.

“Perhaps we have been too scrupulous in the allowances for casting. Mr. Brown is so very conservative, an old woman, I sometimes think, though it shames my sex to say so.”

“Mr. Brown knows his job, and it is the precise cooling that makes the Bigelow wheel the equal of any steel from Pennsylvania. The subway cars are in service almost without stopping.”

Harriet laid her nib on the part of her sheet where several calculations yielded a daily tonnage of molten iron, then made an arc and an arrow point to another corner to escape those conclusions.

“Increase this amount by twenty percent and it is done.”

“Yes.”

“Did you not mention, or rather read to me from a book, the almost magical effects of heating the blast of air before it enters the furnace? You showed me a picture of how it is doneâ¦in Pittsburgh, I think. There is our twenty percent, and more.”

Toma took his pen and crossed out her figures. “That is what I thought, but both Horatio and Mr. Brown told me otherwise. You will make more iron, but the higher temperature puts impurities into the metal, and furtherâ¦further processes are necessary to remove them again. For that, you would need new machines, a whole new plant. The quality of the product is what interests Mr. Stephenson.”

“And the price,” Harriet added sharply. “And the delivery schedule. I wish I had never mentioned this to my father.”

Toma seemed not to notice this petulance, for he was drawing a little map in the last white space left on her sheet of paper. She recognized the river from his rendering of the falls in a few energetic strokes, then the ironworks and the canal, and finally a shape, almost a

rectangle, that was endowed with lines suggesting radiance, and the number 3.

“And what is that?”

“That⦔ he drew fine lines to suggest stones in his sketch, “that is furnace number 3.”

“Number 3 has been plugged for forty years.”

“I know, I have seen it.”

“There is no wheel there, not even a flume or a race now.”

“I know this also.”

“Then why do you botherâ¦?”

“It is your twenty percent.”

“You believe that?”

“I know it.”

Â

A

WEEK LATER,

on a Tuesday morning, Harriet put the finally revised Stephenson contract on her father's desk, having first cleared away some piles of paper and a few catalogues, all of which had acquired a gritty film of dust, aggressive dust that left smudges. Gathering in the necessary charcoal had been a very dirty business, involving such a traffic of wagons, and the blackened raggies made a small mountain of their product above the furnace where once the single storage shed had sufficed. Harriet's hands had not been spared: her cuticles were gray and the same tint traced the slight wrinkles at her knuckles and the creases in her palms. She had been anxious about the quality of each charcoal pit's production, and had helped Mr. Brown with his inspection as the long lines of carts arrived, usually after noon, in the cruelest heat.

She pushed the pot of ink and a pen closer to Amos Bigelow, but her mind was plowing another furrow, and her attention focused on the distraction of those gray lines. Necessary creases, she reasoned with herself, for otherwise the flesh could not bend. Still, she was displeased with what she saw, for it was an advertisement, an exaggeration of a fact that no young person can accept or even believe, except in the most abstract sense. Her hand did not lack grace, but it was large and long, lacking the delicacy of her mother's, those hands that seemed to

grow more beautiful as the disease advanced on her. On her deathbed they had seemed like doves settled on the sunken chest.

No, her own hands were much more like her father's. Now he took the pen and looked into the faces of those gathered thereâHoratio, Mr. Brown, and Tomaâto see if they understood the significance of this moment. She looked intently at his right hand as he made his mark, at those deep crevices lined with the same soot, at the scars of old burns of his tradeâher tradeâand at those other brown marks that were the truest sign of age, and realized with sad astonishment that it was simply a matter of time. She determined to scrub her hands tonight, and every night, no matter how much it hurt, until they were absolutely clean.

“There,” said the ironmaster, “it's done, and may God give us all the strength to carry it through to the finish. What do you say, gentlemen?”

“Amen,” said Mr. Brown, in that odd squeak, as he removed his hat. Horatio nodded silently, as did Toma, who did not think it was his place to speak.

“He drives a hard bargain, my old friend Stephenson. But I guess it's fair enough. Otherwise Harriet wouldn't let me do it, would you, my dear? And you, Mr. Peacock, wouldn't still be here, working night and day as if the devil himself was standing behind you with a pitchfork. Well, boy?”

Toma caught Harriet's eye and allowed himself a brief smile.

“He's a fair man, as you say. And I know that the specifications for the cars have been made more broad because he went in person to the city council to tell them of the quality of the Bigelow wheels. He wrote this to me.”

“Good, good. I'm very glad to know it.” Amos Bigelow seemed pleased but in no way surprised by this mark of confidence. “And when will number 3 be up and running, Mr. Brown?”

Mr. Brown looked at Toma, and Toma in turn looked at Horatio. Brown spoke first: “ThomasâMr. Peacock hereâand the boys have her pretty well cleaned out. That was a terrible mess of iron left in there and we must have broke half a dozen drills just chipping the pieces off it. But it's coming, it's coming. We'll have the new hide on them old bellows tomorrow. The rest is up to Horatio.”

Horatio's long pause may have had something to do with his not

being addressed as Mr. Washington on this occasion. But it had more to do with his mental calculation, or recalculation, of the shafting and gearing necessary to take the power of his wheel several hundred feet to the refurbished furnace, of the slippages in the belting, the compromise in efficiency of the machinery supplying the main furnace with its blast. “Three, maybe four days. The rest depends on the water.”

Everyone in the room knew that since the night of the downpour when the stump had been driven into the headrace, not a drop of rain had fallen on Great Mountain.

Â

H

ARRIET DID NOT THINK

of herself as a deceitful person. Perhaps it is not in human nature to entertain such thoughts; perhaps the most practiced fabulist finds extenuations to explain each exaggeration or violation of the truth, and even the true felon, insofar as he reflects upon his crime, finds that the act was not representative of his nature. Harriet was no criminal; there were several influences in her lifeâthe Church, the Temperance Union, the Chautauqua Circleâwhich encouraged reflections on one's actions, the measurement of one's progress toward a goal of perfection or at least improvement, and these she had embraced with her whole being. That list might also include the admonitory presenceâghost, if you willâof her mother, for in any situation where Harriet struggled to find the path to her own happiness, her fullest flowering, she had to contend with an all-too-lively conception of what her mother would have wanted for her, or would have objected to, and those arguments had a terrible power over Harriet's mind. How can one argue with a ghost?