The Lightning Keeper (22 page)

Read The Lightning Keeper Online

Authors: Starling Lawrence

Â

T

HE FOG HAD NOT

lifted by morning and the sun could not be seen. Mrs. Evans commented on the strangeness of this weather and remembered that such a gloomy damp had been the harbinger of a violent hurricane some twenty years earlier, the same year Harriet had been born.

“I am sure we do not need a hurricane, Mrs. Evans,” said Harriet, “only a little rain. A persistent rain, but not violent.”

“We can't choose, dear, now can we?”

“No. That is simply my hope.” She stopped short of adding that it was her prayer as well, for there the thought or wish must be expressed in a less particular way, and God could answer her prayers in any way He saw fit. Her remark had turned sour on her. She saw that her father had not been following the conversation.

“Time to be going now.” He pushed his plate away. “That boy's up to something.” Here he fixed his daughter with an odd, momentary glance that seemed to go right through her without really seeing her.

It was apparent, once they reached the ironworks, that nearly everyone from the swampers and puddlers to the machinists had reached the same conclusion as Amos Bigelow. There was no one about in the yard, no sound of industry in the forge, no casual banter of men about to go on shift. They saw the square figure of Mr. Brown hurrying off in the direction of number 3.

“Good morning to you, sir! Good morning, miss!” he called out in uncharacteristic exuberance, and then the fog swallowed him.

“By God, will you look!” exclaimed Amos Bigelow. Harriet looked: three black lines slicing diagonally through the thick air, and with the swallows haphazardly perched there, her first thought was for a tipped sheet of music.

The life of the mill was ahead of them now as they hastened along the uneven path, the power train stilled and silent beside them, the black cables converging on their route.

“Don't touch it, Papa.”

Was it her imagination, or had the forest already begun to reclaim the clearing in the few days that number 3 had been shut down? Or was it this odd half-light? The furnace was fired and ready, though with both shifts on hand there seemed to be a great confusion up above on the charging platform and many shouted inquiries addressed either to Mr. Brown or to Horatio Washington, who tended the ugly rust-mottled box that received the cables. He paid no attention to the workmen pressing up as close as they dared to the device.

“I had a cousin once, in Hartford, and he was near killed by the electric when it went wrong,” said one.

“Hmm⦔ said his friend wisely, “and there's them in this very town as has been struck by lightning. Will this thing make lightning, then, Mr. Washington?”

Horatio did not answer, but struck the metal box with his hammer and held up his hand for silence. He pulled three times on a cord, and all eyes followed the cables down to their vanishing point.

Harriet kept her father by her at the edge of the clearing, away from the confusion and the questions.

“Are you frightened then, my dear?” He wondered at the grip of her restraining hand.

“It looks almost like a holiday, don't you think? Or the Independence Day picnic.”

“I think everyone but me knows what's going on here. Can you explain this thing to me? Is Horatio in it then?”

Harriet was never so glad to see Senator Truscott, who now came to stand beside them. What did he know? and how?

“By a single stroke of genius is the world reordered.” Truscott was quoting someone, perhaps himself.

“What?”

“Never mind, Papa. It's about to happen, I think.”

And indeed it did happen, so soon after the answering signal from belowâa small bell tied to a tree near the boxâthat the first thing she noticed was the changing light, a growing illumination like a second dawn as the driven air was fed into the tuyeres by the hidden fan and the flames leapt up from the stack. The motor's whine rose through this spectacle and leveled off at the very edge of her hearing, and the roar of the fan now drowned the cheering.

Could he hear it down there? she wondered. Could he know? She wanted to bolt down the steep path and bring him his triumph like the runner from Marathon.

Fowler Truscott noted the expression on her face, a kind of transfigured beauty, and was reminded of something: yes, that moment in his office so recently. He put his lips very close to her ear.

“Oh, well doneâ¦how very well done indeed.”

“â¦and although I am flattered by your reference to the genius of Mr. Edison, I must also⦔

Here Toma wiped the pen on a scrap of newsprint and put it down. Senator Truscott's note, elegant, and generous, and obtuse, was propped against the battery. The batteryâ¦damnation: he would have to find another one somewhere. Must also what?

The senator's communication was remarkable for its courtesy and timeliness, having been delivered by Harriet Bigelow in person, to the evident displeasure of Olivia. Horatio, as Harriet explained succinctly, was too occupied with the amazing device to come down himself. “And I long to see your wheel.” Her phrase “your wheel” struck a deep chord of pleasure in him. The same phrase, repeated in the senator's note, had an ironic echo.

Of course he had obliged her. She had a knowing smile for the battery and an awed appreciation of the dynamo. They walked together along the belting that linked the dynamo to the waterwheel standing in the wreckage of Olivia's laundry. He gave her his hand to help her through the access hole. She marveled at the spectacle of the wheel enveloped in its own mist and running at full throttle; he would not look at the machine, but at her.

“I cannot tell you⦔ she began. “Horatio said I should be very proud of you. It is such a miracle, this thing. Mr. Brown is beside himself, and promises us twenty-five wheels a day from number 3 alone. Will you show me how it works?”

He nodded in agreement. He noticed that the spray had made a dew on the front of her dress. He put out his hand as if to wipe it away. “H⦔ he said, as she caught his hand in hers.

She glanced down at herself and laughed. “Do I look positively drowned?” Then, not looking at him but at his hand: “Do you remember when you first called me H?”

“I remember everything.” The question and the pressure of her hand must be an invitation, and so he took her in his arms, sweating and work-stained, and found her mouth.

“Your dress,” he murmured.

“It is already ruined. It does not matter.”

Â

T

OMA FOUND

S

ENATOR

T

RUSCOTT'S

letter unaccountably naïve. Flattering, perhaps, but only to a fool. He had invented nothing, and this talk of Edison, the genius of the junk pile, was very wide of the mark. One device to make running water produce electricity, another to make that electricity move the air and feed it into the furnace. The two connected by lengths of borrowed cable. His contribution was no invention, but an application, nothing more than the overcoming of circumstance: Horatio's unwillingness, his own physical limitations, the lack of money, the crudeness of equipment. This is what had tempered his thinking, even in that transcendent moment when the connection of the two wheels had come to him, one for water and one for air. There was tremendous excitement in the enterprise and the accomplishment, but it must not be mistaken for genius.

This was how he understood the matter. He had made no claim for himself or for this solution, had avoided even a description of it in his note to Harriet, not because he was modest but because he was proud: one day he would put his hand and his name to something that would be deserving of such praise. The senator's note, betraying such profound ignorance, was an insult, or so Toma came to feel.

The other awkward point was the reference to “your wheel.” He regretted that he had not corrected Harriet's mistake. It was not his wheel, but Horatio's, and all he had done was tinker with it, adjusting the delivery of the jet to extract the maximum mechanical advantage, reinforcing the timbers supporting the axle to reduce distortion at high

speed. And because of his injury and lack of balance, he had not even been able to do this on his own. Again, it was Horatio, with his fine eye and those huge, steady hands, who brought the wheel to its new position.

Toma stood up and made his way through the shop to the laundry, putting some weight on the foot that was almost healed, trying not to limp. Even at rest the wheel was an undeniably beautiful thing. He set it in motion with a touch and it was as if he had willed some part of his own body to move, so eerily familiar to his hand, such effortless response in spite of the mass.

It seemed as if the spinning might have no end, as if the natural law governing bodies in motion had been defied. There was no sound to it, and only by the quality of reflected light did he know that the wheel was slowing down. The circumference, which had appeared as solid as one of Mr. Brown's iron wheels, resolved itself into the sculpted cupsâeighteen of themâthat received the jet and threw the water back upon itself; the central disk where those corrugations of wood spiraled and tapered toward the axle became a vortex to the eye, more distinct, more mysterious as its speed ebbed. He stopped the wheel with his hand.

Horatio had used a straight and tight-grained beech for his work, preserving it with corrosive sublimate, then tempering it in an oil bath for weeks, gradually increasing the temperature until the water content of the wood was driven out and replaced by the oil. Each piece he had polished, taking care, he said, for his true edges, then were his eighteen pieces laid down in a circle, the heavy cups outermost and the arcing tails like old pipe stems laid toward the center. The splined dowels were seated with a glue that would hold despite the oil, and the whole drawn into a perfect circle by a perimeter belt. When he was done, said Horatio, with a rare animation, as if it had been a contest of strength, when he had executed this one final step that must succeed or fail without reprieve, there was not so much as a drop of expressed glue to wipe away. It was done, and it was perfect.

Horatio knew the quality of his work, and Toma, running his finger in the spiral groove from cup to axle, could find no seam in the wood, though he knew it was there. It was almost as if Horatio had imagined this thing and willed it into existence. Could he make Truscott understand? or Harriet? Did he himself grasp the idea in its entirety? He did not wish to claim the wheel as his own. He was humbled by it,

awed by his sense that there might be properties and potentialities here that he had not yet explored.

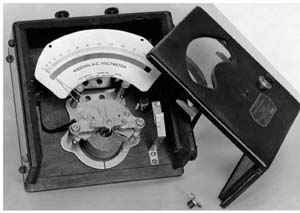

A bell sounded in the shop. That would be Horatio's signal. He opened the jet valve and levered the belt into position on the axle. It was a matter of a few steps to get to the dynamo, by which time he could hear that the wheel was approaching the threshold speed. With two sharp yanks on the cord he answered Horatio, and groped without looking for the clutch lever. His eyes were fixed on the dial and on his crude system of variable resistance. Better to start high than have the motor's coil burnt out by the first rush of unanswered voltage. He clamped the switch to close his circuits and eased the lever to engage the free pulley to the dynamo. The stuttering hum of the wheel was the bass to the dynamo's treble whine, a chord that told him as much as any of the meters arrayed on the bench.

Â

M

UCH LATER, IN THE DAYS

and weeks after he had made his attempts to give an account of the fatal evening, he came back to questions no one else had thought to ask.

The evening was to be a celebration: Olivia had purchased a fine standing roast and had taken the afternoon off in order to cook it, but the heat of the oven made the living quarters of the mill and the shop unbearable. Toma was glad to stand in the spray of the wheel, and when he went back to the shop to check the meters and the sparking of the dynamo, he broke the wary silence to suggest that she come away to the relative cool of the laundry.

“When I'm done,” she replied, intent on paring potatoes. “Horatio is going to want to eat when he comes home.”

At four o'clock, with the clouds already gathering, she walked past the open window of the laundry, unbuttoning her shirtâHoratio's shirtâas if he could not see her, or perhaps she did not care that he did. He moved to the window to watch, knowing where she was headed, and if she did not care there seemed no harm in it. She kept her back to him as she shucked her clothes and lowered herself in to the pool. She had a bit of soap and she washed, still with her back to him, but when she rose from the pool she made no effort to cover herself. She brushed the water away with her hands and made a beautiful

arc of her body to reach her legs, then stood perfectly still to let the air do its work. She wrapped herself in the blue-flowered cloth and walked up past his window without ever once meeting his eyes. He smiled, thinking what a lucky man Horatio was.

They sat down to eat at five-thirty, and Toma poured from the straw-covered flagon of wine that he had asked Olivia to buy with the last dollar he had in his pocket. A thunderclap above Great Mountain drowned Toma's toast to Horatio, and before they had finished the meal the storm broke upon them. Horatio raised his glass to the rain: the water was insurance, he said. Let's hope it doesn't stop.

The bottle of whiskey was put on the table by Olivia after the plates were cleared, and Toma was surprised to see that she took a glass for herself. He had never seen her drink before this evening, and yet she had taken her share of the wine. They were all exhausted: she because the laundry had reverted to punishing hand work; Horatio because the hauling of the cable had come on top of his labor on the motor; Toma because he could only doze, never sleep, while the machinery was running. So the rain was not only insurance: by the time the whiskey was poured there was probably enough water in the Buttermilk to run the main wheel at the works, and Toma could send a signal via the bell-pull. Why didn't they just turn the machinery off and go to bed?

At eight o'clock a messenger with a dead lantern arrived with a message from Mr. Brown that the casting shed had flooded and he was banking down the furnace for the night. By this time Horatio and Toma had moved to the bench to continue, with the help of illustration, a discussion of the Pelton wheel's design and its possible improvement. Whenever Toma caught Olivia in the corner of his eye, she seemed to be looking at him, her arms crossed on her breast and the glass in hand.

Bewick, who had fallen on the path, was glad to take a glass of whiskey while Olivia worked to revive his drowned lantern. He was a Scot, a puddler of many years' experience, and he chose his words carefully. He did not comment on the contents of the glass other than to murmur his thanks. He was more forthcoming in relaying Mr. Brown's opinion of the wheels, and how disappointed he was to have such a fine run of the hearth interrupted.

“But at least there's a good night's sleep in it for you,” he said, raising his glass to Horatio. “We were talking it over, you know, wondering how much longer you could carry on. It's not as if you're a young man, no more'n I am myself. Not like Peacock here.” He drained his glass, nodded at Toma, and belched. “I'll be off now. Mr. Brown had a boy ready to go but I wanted to come and pay my respects. Thank you, missy,” he said, taking the lantern, “I don't know as it will see me all the way home in this rain, but thank you anyway.” Olivia shut the door behind him with unusual emphasis. She had knocked over the lantern twice while threading a dry wick.

The rain drummed on the roof, not in a steady pattern but fitfullyânow drizzle, now downpour. A leak in the roof sent a cascade down onto Horatio's junk pile, and he told Olivia to put a bucket there. The lightning was more constant than the rain, intent on the destruction of the scarred outcropping at the end of Great Mountain. “Lightning Knob,” murmured Horatio. “A betting man could win money on it, if he found a fool to take the bet.”

The temperature had dropped ten or fifteen degrees since they had sat down to dinner. Toma was exhilarated as much by the gift of rain and the electrical display as by the whiskey, but he saw that every time the lightning struck Olivia flinched, and after one particularly violent bolt she crossed herself.

“You know I don't hold with that,” said Horatio.

“Maybe we all going to die,” she answered, looking squarely at him as she drank again.

“Nobody's going to die.” Toma pushed back his chair and went to the bench, to Horatio's rendering of the wheel. “Horatio, will you come with me? We'll need light. I want to show you something, and I want to ask you a question about your wheel.”

“I'm tired, boy.”

“You can sleep tomorrow, as long as you like.”

He had been thinking about the wheel all afternoon, listening to it and rearranging it in his mind, embroidering upon its apparent perfection. He did not think that Horatio saw this thing as anything other than a convenience that had bought him peace with Olivia, a device now turned to another practical purpose.

They took two lanterns each and went to the laundry, and because she would not be left alone, Olivia followed them carrying the bottle. She offered it to him and he refused. He removed the driving belt and spun the wheel with his hand.

“If you stand here, Horatio, you will not get so wet.”

“What am I supposed to be seeing?”

“You are going to see how fast the wheel can go with no load on it and the cock open all the way.”

“I don't need to see anything. What good does that do?”

“I don't know. It will be like watching a horse to see how fast it can go. What good is there in that?”

“I was in the cavalry once. Got a medal, and as far as I remember, that didn't do me any good either. Go fast when you need to. Go slow when you don't. You break this thing, you'll have an awful lot of disappointed folks.”

“I want to see how fast the horse will go,” said Olivia.

“Give me that bottle, girl.” Horatio took it and set it down out of her reach. He turned back to Toma. “You know, there's trouble in this thing if you run it too fast. If you'd ever worked a lathe you'd know what I mean.”

“Here.” Toma handed him the coils of the slack driving belt. “If the axle starts to vibrate you can ease it down. But I think you'll see that I was right and the wheel will find its own limit.”