The Lightning Keeper (24 page)

Read The Lightning Keeper Online

Authors: Starling Lawrence

“Will you listen? Something happened to the wheel in the accident, even before the accident.”

Toma looked away to the calico curtain, and so Truscott looked too. There was the woman, carefully dressed, as if for church. How long she had been there he did not know. No words were spoken between them, and Truscott found the silence oppressive. A strange business, this. If it had been an affair of white people there would have been an inquiry of some sort. He cleared his throat.

“About the wheel?”

“We were experimenting with the system and there was an event, an accident, that altered the wheel. It was a mistake.”

“So: a pointless experiment leads to a lethal mistake. A man's life is wasted, and while the fate of the Bigelow Iron Company hangs in the balance, you carry on as if nothing had happened. Have you no shame, sir?”

Toma glanced up and spoke very slowly, as if he doubted Truscott's understanding. “You will not speak to me of shame nor teach me how to grieve. I am responsible for the accident but sorrow will not raise Horatio from the dead, and so I ask myself: Why did he die? Because the wheel, without those blades, or cups, went faster than before. You had only to listen. So fast that its vibration broke through the frame. Then Horatio danced with the wheel and was gone.”

“And he died, as everyone knows. So⦔

“So now the idea of the wheel lives. The sound of it is in my head as if I am the measuring device; and lives, or very nearly, somewhere on my papers there. When its secret is known to me, then I will need your money.”

Now Toma smiled as if some weight of indecision had been lifted from him. Truscott was on the point of responding to this visionary

impertinence when suddenly he saw his path converging with Toma's. It never pays, he thought, to get angry. When he spoke now he sounded much more like himself.

“You will build this new thing, then, whatever it is, and not the old one?”

“Yes. If not now, then never. It will be lost. All will be lost, and Horatio's death will mean nothing.”

Truscott's mind raced ahead of his understanding. From a certain point of view, all was lost right here, right now. What might be salvaged? “Are you saying, in effect, that the hand of God came down and altered the wheel, made it perfect, and in so doing killed Mr. Washington?”

“I do not say it was the hand of God.”

“You do realize that Miss Bigelow will be disappointed?”

“I can do nothing about that. Perhaps she will understand the importance of this new work.”

“We must hope so. But in the meantime she will see only loss in your resolve.” While he spoke, the senator was making rudimentary calculations of his own losses, to be offset by the prize. This was going to be a very expensive matter. “Well, I've done my best here, all I could do. You are determined on this?”

“I am.”

“And, so that I might explain it better to Miss Bigelow, what benefit or improvement did the accident confer?”

“Ten percent, I am sure, perhaps as much as fifteen, judging from the song of the wheel.”

“Fifteen percent. I say.”

“Perhaps. The acceleration is along the curve that you hold there in your hand.”

Truscott considered the wood with blank amiability. “My dear sir, do not confuse me with technical matters. I must take you at your word. But if you are correct, I do know some persons of influence who will most certainly understand. We shall talk again. And in the meantime?”

“For now I need nothing, only time.”

“I got to go.” Olivia put her hat on.

The senator was pleased to find his jacket somewhat drier than before. “Then we shall go up together, Mrs. Washington, and may I ex

press my deepest sympathies for your loss.” Olivia stared at him without expression, and so he turned to Toma. “Good luck to you. I hope to hear from you soon. I am at your disposal.”

On his way back up the hill Senator Truscott followed Olivia in silence and at a respectful distance. But, being a man, he could not help noticing the provocative grace of the figure aheadâher buttocks were more or less at his eye levelâand he wondered about the curious tragedy that had befallen her. Past the ironworks they went in this configuration and out onto the road. They parted without acknowledgementâhow could he address her back?âshe heading toward the pink stucco pile of her church, and he to the hewn stone of his bank. His final reflection was that she must be roughly the same age as Harriet or perhaps a bit olderâit was hard to tell with these peopleâand that Horatio might have been as old, or as young, as he.

Â

“I

DON'T UNDERSTAND,”

said Amos Bigelow. “Everything was working well, and now this. It is an uncivil letter, and from an old friend.”

“Mr. Stephenson is only exercising his judgement as a businessman, and his right. The fact is that we did not, could not, deliver the wheels as we had contracted to do.”

“But he has enough to start? We ship every week's production to him. Can there be such bother about an unavoidable delay?”

“The contract, I fear, was specific on this point. There is a penalty for nondelivery of any part of the order. I suppose he has contracts and obligations as well, perhaps with penalties.”

“And Mr. Brown?”

“He has done his best under the circumstances.”

“That boy Peacock? Why hasn't he done something?”

Harriet could find nothing to say.

“What a mistake it was to put any faith in him. Well, well, it's done now and the fat is in the fire. Tell me, my dear, what I must do.”

“I will write to Senator Truscott of this development. He will know what must be done.”

TEN

The wooded environs of Great Mountain are a most pleasant adjunct to the civilized charms of Beecher's Bridge, and we make no doubt that the growing reputation of our town as a summer resortâwe cannot quite call it a spaâis enhanced by the bracing propinquity of such apparent wilderness.

The air, of course, has always been refreshing, and is now, with the suspension of enterprise at the Bigelow works, more so than ever. A second hotel, the Mountain View, has been erected and does an excellent businessâespecially during the high seasonâin friendly competition with Mr. Shepherd's older establishment. The table at the Mountain View is certainly noteworthy, and Monsieur Boule, the chef, has set his hand to dishes that would be more familiar to the citizens of Paris than to our native New Englanders. Mr. Shepherd has not swerved from his plain fare of roasts, puddings, and local produceâyou will never encounter the bleached asparagus or the hothouse grape on his tableâbut he has responded in other ways. What visitor can fail to be impressed by the recent renovation of the Shepherd's public rooms, including those dramatic Tiffany windows in the entrance hall and on the stair landing, the splendid girandoles blazing in the evening, and the impressively carved and upholstered items of furniture in the lounge? (The proprietor of the Mountain View has referred to these with uncharitable humor as “Pope-ish thrones.”) And the one thing that adherents of either establishment can agree on is the sense of re

lief that their repose is untroubled by the distant hammerings of the forge, and that the snowy aspect of a starched collar or lace cuff is not under constant threat from industrial soot. There was much to be regretted in the passing of the Bigelow Iron Company, but much to be gained as well. The Lord giveth, and the Lord taketh away.

We are a little in advance of that high season just now, this being only the middle of May, but there are guests enough at the Shepherd even so. Some are en route to the Berkshires; some are resting before the season in New York; there is a gentleman from Concord who can tell you a great deal about the niceties of Congregational Church architectureâ¦in fact he

will

tell you, unless you are deaf; and there are two botanizing ladies whose knowledge of our flora puts the local amateurs quite to shame. Well, we must make the best of any situation, and there is the prospect of a rubber of bridge after dinner or at least a decent cigar and a game of billiards with the proprietor.

The excellence of the standing roast coupled with dread of the Concord encyclopedia have occasioned this energetic outing in the direction of the mountain, by that scenic carriage route known as the Five Mile Drive. A spirited mare from Mr. Moore's livery steps out as if the stanhope were of no weight or consequence. In passing the triangular green and the Congregational Church we noted with approval the new construction of rustic bentwood trellises and gazebos that will shade the strollers in high summer, and saw that the protective winter sheathing of Mr. Stanford White's splendid bronze and granite fountain has been removed so that we may once again marvel at those tritons and spouting dolphins.

But now, at about the midpoint of our circuit, we stop and tie the mare to a stone post that marks the beginning of a foot trail leading up the mountain into the wilderness.

Wilderness is a euphemism when applied here or anywhere in the state of Connecticut. There may be pockets of the aboriginal forest, usually in those steep descents where the raggy or the tannerâwhose quarry was the hemlock barkâknew better than to risk injury to himself or his horses. But here we see the old stone walls running beside the road in the shade of substantial pines and occasionally caroming off into the shade and out of sight. This is no wilderness but the abandon

ment of human labor and habitation, the relinquishing of an old economy of field and pasture.

What lesson is there in this history? Ezekiel tells us that all is vanity; an extreme view, perhaps, but irony is certainly a useful tool to the historian.

We have previously noted the ambitious scheme of the Grand Canal, so called, and Power City, and the troublesome legacy of Aaron Bigelow's ambition. No doubt Mr. Amos Bigelow sees himself as a victim of history. Well, our mountain has other victims as well, and not just individuals who hoped foolishly or dared too much, but entire communities that have failed.

Beyond that ridgeline there, on the northeastern flank of Great Mountain and just at the limits of our township, was situated the hamlet of Meekertown, at a distance of some seven miles from the center of Beecher's Bridge. Not much is known about Meekertown or its inhabitants, and even its exact location is a subject for speculation. We imagine it to have been a simple farming community, well watered, but with no advantage of soil, as the early settlers avoided the rich river bottoms in favor of hilltops, fearing the damp and vapors. But it was not poverty of soil that doomed Meekertown, rather the poor opinion of its neighbors.

The simple farmers of Meekertown had no post office and no church. There may have been a general store, but if so it was a modest one. For all needs beyond the most basic, then, a pilgrimage to Beecher's Bridge was required, and seven miles is a considerable journey in these hills, especially in winter. What we have to go on here are the tithe books of the Congregational Church, holographs of two sermons by Dr. Robbinsâthey were not included in his

Collected Sermons

âand several diary entries by Mrs. Hoover's great-grandmother, a lady with an omnivorous curiosity and some decidedly Old Testament instincts.

It would seem that the inhabitants of Meekertown gradually fell away from that strict and enthusiastic observance of the Sabbath required in the early days of the past century, and so earned the censure of the people of the town, for whom the service entailed only a stroll across the green, or a brief ride in carriage or sleigh. The decline in

attendance seems to have been gradual rather than precipitous, and more pronounced in those grim winter months. We have some sympathy for their situationâpractical needs could not be addressed on the Sabbath, and what if the horse were lame?âbut the right-minded citizens of Beecher's Bridge had none. Mrs. Hoover's ancestress made note of each empty pew, and the Reverend Robbins had harsh words for Meekertown and its people, even a reference to Sodom and Gomorrah.

Did the townspeople recoil from contact with such slack spirituality? Were lines of credit at the general store and the bank closed down? We cannot help but take the charitable view that the farmers of Meekertown were not so much degenerates as they were victims of geography.

Of Meekertown itself there remains no trace and the property records were destroyed many years ago in a fire in our town hall. The last remaining inhabitant of that vicinity, a Mrs. Wilms, died in 1896, with the taxes on her farm several years in arrears. She was almost never seen in town. It was said that she had a set of wooden teeth and that she would cut the toes off her hens to keep them from scratching in her yard, where there were a few flowers. We visited her a year or so before her death in an effort to ascertain the exact location of the original hamlet. (The report of her dental equipment seemed accurate, but there was not a chicken or flower in sight.) Unfortunately, age and the years of isolation had taken a toll on her mental process, and she could not recall that there had ever been any other inhabitants on that part of the mountain. The one clear thought in her head was that she had been struck by lightning in a hailstorm in the summer of 1851. The second time she told us this she pushed back the sleeve of her shapeless woolen garment to show a faint but unmistakable fern-leaf pattern on the withered flesh. We had heard of such a marking of lightning's victims, but had never before seen the evidence.

The property in the area of Meekertown was acquired piecemeal by Aaron Bigelow for the outstanding taxes, and became part of that extensive charcoal-cutting preserve known as the Bigelow Plantation. And so the tragedy of Meekertown is folded into that larger historical narrative of which Amos Bigelow feels himself to be the inheritor and the victim.

It is just as well that Mr. Bigelow resides in Washington just now; otherwise this damp glory of our spring must depress him, for the relatively mild winter and the torrents of April would have been encouraging to iron production. See how the trail ascends here! And do you mark the music of falling water just ahead?

If we will look upon history as a catalogue of vanished communities and failed enterprise, then its study must be as discouraging as the face of that old woman who remembered nothing, not even the name of her deceased husband. But would not the sensible writer or philosopher also take note of a parallel history, consisting of those invisible yet tenacious motors of progress that we have referred to as dreams? And what a rich and colorful vista presents itself to us now, as subtle in its interweaving of the mutable and the eternal as the very landscape before us, where new shoots and flowers proceed from stumps that have slept through the winter.

Communities as well as individuals have their formative dreams, and we need look no further than our own town to find that this is so. For Beecher's Bridge has not withered away with the passing of the ironworks, though no doubt there is economic distress in many a household along the Bottom. Instead, and with the active encouragement of Senator Truscott and his bride, we have embraced a higher or at least more refined idea than mere manufacture: the promotion of tourism upon the pillars of healthful recreation.

Consider these improvements of the past two years: there is the splendid new organ in the Congregational Church, and a most accomplished organ master, both funded by generous gifts from the senator; we are now the seat of the Litchfield Choral Society, with concerts twice weekly during our summer season; and perhaps most significantly, there is an agreement with the great university in New Haven that the music schoolâone of whose professors holds the recently endowed Truscott Chairâwill hold its summer session in Beecher's Bridge, a trial arrangement that has every likelihood of becoming a permanent feature of our summers. The wanderer in such pleasant seclusion where we now find ourselves may, in the coming months, be entertained by the distant strain of a flute in the Greenwoods.

There are varying degrees of enthusiasm for this new direction in

the affairs of Beecher's Bridge. Amos Bigelow, for example, cannot be expected to embrace this new possibility, any more than would the idled furnace man who cannot play the flute. How do the dreams or strivings of individuals interact with one another or circumstance to form the general or communal thing? Well, this theory of the parallel history of dreams is the fruit of this very outing, and, like anything newborn, must not be tested too soon or too severely.

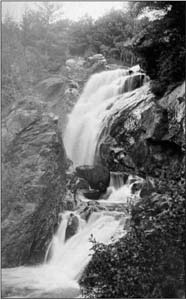

Now that we have arrived at our destination, this glen with its picturesque falls so near the highest reach of the mountain, we observe that we are not alone. For here, seated by the falls, staring at the tumbling water, is Mr. Thomas Peacock, late of the ironworks and now engaged in researches that may in time redirect the fortunes of Beecher's Bridge. Were we to engage him in conversation, no doubt he could shed light on the lines of our inquiry, for he is a man with his own fierce aspirationsâ¦dreams, if you will. But there is an unwritten etiquette of the Greenwoods, and people will come here with various ends, some best pursued in silence. If he has seen us he makes no sign, and so, rather than risk an encounter that is not mutually welcome, we shall withdraw. By the time we reach the carriage there will be a slight chill in the air, and the impatient mare will carry us home to tea.

Â

T

HE GULLY IS KNOWN

as Rachel's Leap. A little way down the mountain the watercourse is shaded by old-growth hemlock trees, and the steeples of rock are humid and green. There is little light or air, and no view at all.

Near the top, the growth is mostly scrub oak, and from the first waterfallâPothole Fallsâthere is an impressive view out over the valley of the Buttermilk. But Toma is lost in his thoughts and has scarcely raised his eyes from the water. This has long been a popular spot for courting couples, and the irony is not lost on Toma; in fact it has everything to do with his being here. Today is his birthday, his twenty-fourth, and exactly a year ago he left the silk mill in the morning and walked up the mountain to these falls to be alone with his thoughts and mark this day. Why this place? He had found it on his own in the course of one of his scavenging tripsâHoratio had a map of old mill

sites on the mountain, with an inventory of their equipmentâand something about the landscape reminded him of Montenegro, and so of his family and Harwell and Lydia too, who were the only ones who might remember the significance of this day.

To his great surprise, he found that he was not alone at the falls, and the woman on the far side, who had apparently arrived by a different path, was Harriet Bigelow. He had not seen her at first, and even then did not recognize her. But when she threw back her shawl and turned her face to the sun, he knew her. They had not spoken since the failure of the ironworks.

“Toma!”

He smiled and made an awkward half bow in her direction.

“Well? Are we never to speak again? Or are you waiting for me to come to you?”

There was still snowmelt to swell the stream and Toma could not, as he might have done in August, simply step across on the large rocks. He hopped once, twice, with perfect luck, but he fell short on the third, which would have brought him safe and dry to her side. She laughed at him, or with him, as he emptied out his boot.

“That was almost perfect.”

“I was too ready to obey. I should take my boots off to wade. But there, you see, I could not.” He pointed to the purple scar on his naked foot.

“Oh! I am so stupid. How could I not have remembered? Did you hurt it again just now?”

“No, it is nothing. But it is ugly to see.”

“Yes. Your perfection is quite spoilt.” Her tone was mocking, but her eyes were warm. “I should not have asked you to do it.”