The Lonely Sea and the Sky (28 page)

Read The Lonely Sea and the Sky Online

Authors: Sir Francis Chichester

I felt intensely lonely, and the feeling of solitude intensified at every fresh sight of 'land', which turned out to be yet one more illusion or delusion by cloud. After six hours and five minutes in the air I saw land again, and it was still there ten minutes later. I still did not quite believe it, but three minutes later I was almost on top of a river winding towards me through dark country. A single hill rose from low land ahead, and a high, black, unfriendly-looking mountain range formed the background. A heavy bank of clouds on top hid the sun, which was about to set.

Well, this was Australia. Away to the south lay a great bay, and at the far side I spotted five ships anchored. They were warships. I flew south, and crossed the bay. Flying low between the two lines of ships I read HMAS

Australia

, HMAS

Canberra

. On the other side there appeared to be an aircraft-carrier. My heart warmed at the thought of getting sanctuary there, but all the ships had a cold, lifeless air about them. I supposed that I must fly on to Sydney. I flew over an artificial breakwater near a suburb of red-bricked, red-tiled, bungalows and houses like a small suburb in a dull-brown desert, with only a few sparse trees of drab green. There was not a sign of life, and not a wisp of smoke from the chimneys. Had the world died in my absence? If there was anyone left alive, there would surely be a watchman on one of the warships. I turned and alighted beside the Australia, its huge bulk towering above me. The seaplane drifted past and away from it, bobbing about on the cockling water. There was dead silence except for the soft chop chop chop against the float. I felt a fool to drop into this nest of disdainful battleships. I stood on the cockpit edge, and began morsing to the Canberra with my handkerchief. An Aldis lamp at once flashed back at me from the interior of the bridge. A motor-launch shot round the bows of the warship. I cancelled my signal, and stood waiting. 'How far is Sydney?' 'Eighty miles.'

Australia

, HMAS

Canberra

. On the other side there appeared to be an aircraft-carrier. My heart warmed at the thought of getting sanctuary there, but all the ships had a cold, lifeless air about them. I supposed that I must fly on to Sydney. I flew over an artificial breakwater near a suburb of red-bricked, red-tiled, bungalows and houses like a small suburb in a dull-brown desert, with only a few sparse trees of drab green. There was not a sign of life, and not a wisp of smoke from the chimneys. Had the world died in my absence? If there was anyone left alive, there would surely be a watchman on one of the warships. I turned and alighted beside the Australia, its huge bulk towering above me. The seaplane drifted past and away from it, bobbing about on the cockling water. There was dead silence except for the soft chop chop chop against the float. I felt a fool to drop into this nest of disdainful battleships. I stood on the cockpit edge, and began morsing to the Canberra with my handkerchief. An Aldis lamp at once flashed back at me from the interior of the bridge. A motor-launch shot round the bows of the warship. I cancelled my signal, and stood waiting. 'How far is Sydney?' 'Eighty miles.'

I dreaded the thought of Sydney, and its crowds, but my job was to reach it. The launch was crowded with sailors, and at 20 yards their robust personalities gave me a feeling of inferiority. I felt that I had to get away quickly. I asked the launch to tow me to the shelter of the breakwater, and a sailor slipped me a tow rope efficiently. I climbed out on to the float to swing the propeller, and as I swung it I noticed mares' tails of sticky black soot on the cowling, due to the backfires. I wondered if the engine still had enough kick to get me away, but as soon as the seaplane started moving forward and pounding the swells, the futility of trying to take off was obvious. That settled it; I had to ask for help. The launch approached again. 'We'll tow you to

Albatross

,' an officer said. I made fast the tow line and I was towed up to the aircraft carrier, where I made fast to a rope dangling from the end of a long boom. I released the pigeons, feeling sorry for them, and they took off flapping and fluttering, presumably for their home loft near Sydney. A sailor let down a rope ladder from the boom, and I grappled clumsily up it, my feet often swinging out higher than my head. I made my way along the boom to the deck where a commanding figure, with much gold braid, was waiting for me. 'Doctor Livingstone, I assume,' he said, looking hard at me. 'At any rate, you have managed to discover the only aircraft carrier in the Southern Hemisphere. Come along to my cabin.'

Albatross

,' an officer said. I made fast the tow line and I was towed up to the aircraft carrier, where I made fast to a rope dangling from the end of a long boom. I released the pigeons, feeling sorry for them, and they took off flapping and fluttering, presumably for their home loft near Sydney. A sailor let down a rope ladder from the boom, and I grappled clumsily up it, my feet often swinging out higher than my head. I made my way along the boom to the deck where a commanding figure, with much gold braid, was waiting for me. 'Doctor Livingstone, I assume,' he said, looking hard at me. 'At any rate, you have managed to discover the only aircraft carrier in the Southern Hemisphere. Come along to my cabin.'

I felt like a new boy in front of the headmaster. 'Did I say, when you came aboard, "Doctor Livingstone, I assume?" Of course, I meant, "Doctor Livingstone, I presume?".' But Captain Feakes of the Royal Australian Navy was a great host. He gave me a whisky and soda and made me feel like a long-expected, favourite guest. Yet I felt isolated, and drained of personality, horribly cut off from other people by some queer gulf of loneliness. I had achieved my great ambition, to fly across the Tasman Sea alone, I had found the islands by my own system of navigation which depended on accurate sun-sights worked out while flying alone, something which no one had ever done before and perhaps no one ever would do in similar circumstances. I had not then learned that I would feel an intense depression every time I achieved a great ambition; I had not then discovered that the joy of living comes from action, from making the attempt, from the effort, not from success.

Squadron-Leader Hewitt of the Australian Air Force arrived and offered to lift the seaplane on board

Albatross

. I asked him to let me do the job of hooking on. It was dark when I went on deck. An arc-lamp shed a brilliance high up but only a dim light reached the seaÂplane as she was towed slowly under the lowered crane-hook. Standing on the top of the engine of the bobbing seaplane I tried to catch the ponderous hook; it was a giant compared with the one at Norfolk Island, with a great iron hoop round it, probably a help in hooking on big flying-boats, but only adding to my difficulties. I had to duck the hoop to catch the hook with one hand, and reach under it with the other to keep the two sling wires taut with the spreaders in place and the middle points of the wires ready for the hook. The hook itself was so heavy that I could not lift it with my arm outstretched. The seaÂplane was rolling, and also there was a slight movement of the aircraft carrier, sufficient to tear the hook from my grasp, however tightly I clung with my knees jockeywise to the engine cowling. At last I had the wires taut and the hook in place under them, when either the seaplane dropped or the aircraft carrier rolled unexpectedly. The hook snatched and lifted the seaplane with my fingers between the hook and the wires. The pain was excruciating, as the wires bit through my fingers. I shrieked. I felt ashamed; but I knew that my cry was the quickest signal I could give the winchman. The hook lowered, and I sat on the engine top, knees doubled up, leaning against the petrol tank. I could not bear to look at my hand. The hook swung like a huge pendulum above me. I felt, well, I had bragged of my skill at this job; I should just have to get on with it. I cuddled the round of the iron hook in the palm of my right hand, and rested the wires in the crook of my thumb of the other hand. Everything went easily. 'Lift!' I said. The water fell away, and at last the seaplane swung inboard, stopped swinging, and dropped softly on to padded mats. I said to a man standing by, 'Help me down, will you? I am going to faint.'

Albatross

. I asked him to let me do the job of hooking on. It was dark when I went on deck. An arc-lamp shed a brilliance high up but only a dim light reached the seaÂplane as she was towed slowly under the lowered crane-hook. Standing on the top of the engine of the bobbing seaplane I tried to catch the ponderous hook; it was a giant compared with the one at Norfolk Island, with a great iron hoop round it, probably a help in hooking on big flying-boats, but only adding to my difficulties. I had to duck the hoop to catch the hook with one hand, and reach under it with the other to keep the two sling wires taut with the spreaders in place and the middle points of the wires ready for the hook. The hook itself was so heavy that I could not lift it with my arm outstretched. The seaÂplane was rolling, and also there was a slight movement of the aircraft carrier, sufficient to tear the hook from my grasp, however tightly I clung with my knees jockeywise to the engine cowling. At last I had the wires taut and the hook in place under them, when either the seaplane dropped or the aircraft carrier rolled unexpectedly. The hook snatched and lifted the seaplane with my fingers between the hook and the wires. The pain was excruciating, as the wires bit through my fingers. I shrieked. I felt ashamed; but I knew that my cry was the quickest signal I could give the winchman. The hook lowered, and I sat on the engine top, knees doubled up, leaning against the petrol tank. I could not bear to look at my hand. The hook swung like a huge pendulum above me. I felt, well, I had bragged of my skill at this job; I should just have to get on with it. I cuddled the round of the iron hook in the palm of my right hand, and rested the wires in the crook of my thumb of the other hand. Everything went easily. 'Lift!' I said. The water fell away, and at last the seaplane swung inboard, stopped swinging, and dropped softly on to padded mats. I said to a man standing by, 'Help me down, will you? I am going to faint.'

When I came to I was in the ship's hospital. My right hand was crushed, but I lost only the top of one finger. The surgeon cut off the crushed bone and sewed up the flesh. I then became the guest of the wardroom officers as well as of Captain Feakes, and it is hard to recount such marvellous hospitality. It was like staying in the best club with the mysterious fascination of naval life added.

PART 3

CHAPTER 17

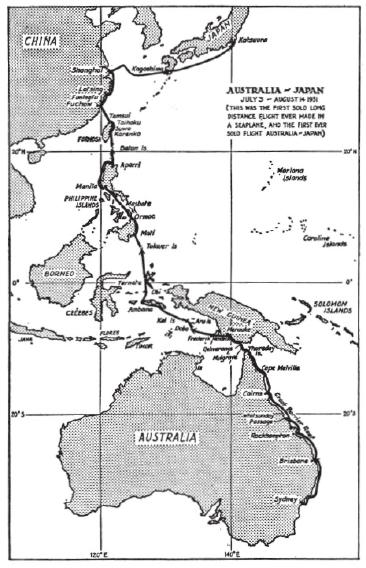

FIRST STAGE TO JAPAN

The Australian Navy took me into Sydney Harbour, and then I had to set about finding refuelling places and the necessary permits for the second half of my flight round the world. With the

Gipsy Moth's

range as a seaplane reduced to 600 miles, I had to find a sheltered river or inlet every 500 miles or so where the half-ton seaplane could ride out the night at a mooring, and where there was someone who could understand my talk or signs, and where I could get some petrol.

Gipsy Moth's

range as a seaplane reduced to 600 miles, I had to find a sheltered river or inlet every 500 miles or so where the half-ton seaplane could ride out the night at a mooring, and where there was someone who could understand my talk or signs, and where I could get some petrol.

The first 2,000 miles up the coast of Australia was easy enough; the difficulties started with New Guinea. Merauke sounded all right; a steamer called there once a month. But where could I find a spot within range after that? The Admiralty Sailing Directions were the only guide I had at first:

'Frederik Hendrik Island... about 100 miles long... everywhere covered with dense forest and so marshy as to be almost inaccessible.'

'The Digul River... the natives were hostile, the boats and bivouacs being repeatedly shot at.'

'The Inggivake... twice shot arrows at the boats.'

Kaimana Bay seemed my best hope, it had several houses with corrugated iron roofs, but it was 600 miles from Merauke. Fortunately I met a Dutch skipper who knew the Arafura Sea well, and he told me that the settlement at Kaimana had been withdrawn and that Fakfak, 700 miles away, was the nearest place to Merauke. So the only hope seemed to be for me to dump some petrol myself in a creek, and return to Merauke to fill up again. My Dutch skipper said that if I alighted alone at 10 o'clock, I should be in the stewpot by noon; he said, 'Why not fly from Merauke to Dobo, the pearling centre in the Aru Islands 480 miles west of Merauke?'

The Dutch Government refused me permission to fly over New Guinea unless I guaranteed to repay any expenses incurred in looking for me. I imagined myself working for the rest of my life to pay for a week's cruise of the Dutch fleet. Later, they allowed me to fly to the East Indies if I signed a form absolving them from any responsibility. I was happy to do this, for I did not want anybody to go searching for me if I got into a mess. What I did not know was that the Dutch had cabled to New Zealand, and two of my friends, Eric Riddiford and Grant-Dalton, had guaranteed payment of any expenses incurred without saying anything to me about it.

While I wrestled with consuls to get permits, de Havillands gave my engine a complete overhaul. Some of the pistons were cracked, and the crank-shaft was full of sludge. One of the worst mistakes I had made in reassembling the engine was to screw up the propeller-shaft thrust-race too tight, and only a shimmy of it still remained when I reached Australia. Nothing could be found wrong with the magneto which had cut so mysteriously over the Tasman Sea, but the other one, which had kept on spluttering and misfiring, had a cracked distributor, and they showed me a long blue spark jumping the terminals when it was tested. Major Hereward de Havilland, known to everybody in Sydney as 'DH', red-faced with a deep slow voice, was an interesting friend. He liked to probe everything until he found the reason for it. Why was I attempting this flight which he considered impossible? Why did I not buy a yacht and sail round the world instead of flying? It was more comfortable, cheaper, safer and healthier. After a fortnight of wrestling with people and difficulties it did seem to me like paradise to be sunbathing on the deck of a yacht. Thirty years on, now that I am a sailing man, this idea seems a great joke; I get far more sunbathing in the middle of London in a month than I ever have on a yacht! Hereward had one theory that, I believe, was valuable and true; the only way for a flying man to keep alive was to be apprehensive.

Captain Feakes had allowed me to leave the seaplane in

Albatross

. It was not until then that the flight-sergeant found one of the bilge compartments full of water; it had not been discovered before because a chock under the float had prevented the drain plugs being opened. The strange thing was that the aircraftman could not find any leak in the float. I asked de Havillands to have a good look when they replaced the engine, but they too could not find anything wrong. If ever fate wove a web it was round that bilge compartment.

Albatross

. It was not until then that the flight-sergeant found one of the bilge compartments full of water; it had not been discovered before because a chock under the float had prevented the drain plugs being opened. The strange thing was that the aircraftman could not find any leak in the float. I asked de Havillands to have a good look when they replaced the engine, but they too could not find anything wrong. If ever fate wove a web it was round that bilge compartment.

Nothing was going right with my preparations. I could not get any decision about where I could alight en route, and so could not make any arrangement for petrol supplies. No money arrived from New Zealand; my finger refused to heal; finally, I asked Hereward if he would lend me some money. He turned up trumps, and I set off for Japan with £44 in my pocket, with which I was to pay for all my expenses, and buy my petrol as I needed it on the way.

So one chilly early morning the great hatches were rolled back, and the

Gipsy Moth

hauled up from the giant hold of the

Albatross

. When I tried to thank Captain Feakes and the others, he drew me aside and said, 'If you find it's impossible, give it up, won't you?'

Gipsy Moth

hauled up from the giant hold of the

Albatross

. When I tried to thank Captain Feakes and the others, he drew me aside and said, 'If you find it's impossible, give it up, won't you?'

He offered to have the seaplane launched for me, but I declined, mounted the cowling, and held the crane hook under the sling wires myself. The seaplane was swung outboard and lowered to the harbour surface. Lazy wisps of smoke hung about buildings. The soft grey shapes of the moored warships suggested a peaceful existence. That glassy surface was a worry for me, though. The floats would not be able to break from the suction of smooth water; with the Captain on the bridge, and my friends watching, I should be unable to take off. I had to try, though, so first I headed for the harbour entrance. The water felt like treacle, and I turned and headed for Sydney Harbour Bridge, but I could not break the grip of the surface. Suddenly I spotted a ferry steamer ahead, swerved, and made for the waves of its wash. I felt a bump-bump-bump underneath, and we were off. I dipped my wings to Al

batross

and headed for the open sea. It was wonderful to be roaring north. I wrote in my log, 'This is the supreme ecstasy of life.'

batross

and headed for the open sea. It was wonderful to be roaring north. I wrote in my log, 'This is the supreme ecstasy of life.'

Other books

After We Fell by Anna Todd

The Danish Girl by David Ebershoff

Juice: The O'Malleys Book 1, contemporary Adult Romance by Michelle McLoughney

Paradise - Part Two (The Erotic Adventures of Sophia Durant) by Casper, O.L.

Stormcaller (Book 1) by Everet Martins

Bombers' Moon by Iris Gower

Bible and Sword by Barbara W. Tuchman

Roaring Thunder: A Novel of the Jet Age by Boyne, Walter J.

Saxon Bane by Griff Hosker

September Song by Colin Murray