The Long Tail (11 page)

Authors: Chris Anderson

A team at the University of California, Berkeley, illustrated this with a new map of creation, as follows.

As this figure shows, a once-monolithic industry structure where professionals

produced

and amateurs

consumed

is now a two-way marketplace, where anyone can be in any camp at any time. This is just a hint of the sort of profound change that the democratized tools of production and distribution can foster.

HOW TO CREATE AN AGGREGATOR THAT CAN STRETCH FROM HEAD TO TAIL

In 1982, a

bookseller named Richard Weatherford realized that the then-new personal computer could revolutionize the used-book business. There are thousands of used-book stores around the country, all with different inventories. Virtually any book you might want is out there somewhere, but good luck in finding it. Weatherford saw this as primarily an information problem, exactly the sort of thing computers are good at solving, and he wrote a business plan for a company that would build an online database for antiquarian booksellers. He called it Interloc, short for interlocutor, a fancy way of saying “go-between.”

Weatherford was a few decades ahead of his time, and he failed to get funding. But in 1991, he was hired by Faxon, a book and magazine service firm, to salvage BookQuest, which had attempted to do the same thing. It didn’t work—this was still about a decade too early—but the funding at least was starting to become available. With $50,000 from other booksellers, Weatherford launched Interloc in 1993, before the Web. It was a closed network to enable booksellers to search other merchants’ inventory to find books for their own customers. It created a data standard (which is still in use today) and soft

ware that allowed sellers to transfer files of book listings over a modem. In 1996 it expanded to the Web.

In 1997, Marty Manley, a former union leader, McKinsey consultant, and assistant secretary of labor under Bill Clinton, was looking for an out-of-print book. He found Interloc, and was immediately struck by the potential of such a rich database of information in the fragmented book market. He got in touch with Weatherford and proposed merging Interloc into a new company, tailored to both consumers and booksellers alike; later that year they launched Alibris in Manley’s home in Berkeley.

It’s worth taking a moment here to understand the used-book market. For most of the past few decades it has actually been comprised of two very different markets. About two-thirds of it was the thriving and efficient textbook business that centered around college campuses. The other third was a relatively sleepy trade in around 12,000 small used-book stores scattered around the country.

Used textbooks are a model of an efficient market—every year millions of students buy and then resell expensive volumes they need only for a single semester. The set of books with resale value is determined by the published curriculum of core classes; the price is set by what competition there is between campus bookstores; and the supply is replenished twice a year.

Textbook publishers don’t mind this very much because it means they can actually charge more for new copies, since the buyers know they have a predictable resale value. Indeed, the economic model at work here is more like a rent than a purchase. Typically, stores buy books for 50 percent of the cover price and then resell them for 75 percent. Depending on whether the student is buying new or used, that “rental fee” is between half and a quarter of the list price of the book. This arrangement works so well that the used-textbook market in the United States is now a $1.7 billion enterprise, accounting for 16 percent of all college store sales.

Publishers ensure that the used books don’t circulate forever, which would depress new book sales, by releasing new editions with different page numbers (so the old ones can’t be used). This purges the market of old inventory from time to time.

In the case of the non-academic used-book market, however, there were few of these efficiencies. The typical used-book store’s access to secondhand books is limited to whomever happens to be local and selling volumes from his or her own collection. As a result, the selection at these stores tends to be pretty random, reflecting the taste of the proprietor and the luck of the catch rather than any comprehensive slice of the book market. For patrons of used-book stores, this randomness is part of the appeal, providing a serendipitous sense of exploration and discovery. But if you’re looking for a particular book, that process of cruising around the store and browsing the shelves can be unrewarding.

In economic terms, what makes the textbook market work is ample liquidity. There are so many sellers and so many buyers of a relatively small set of traded commodities that the odds of finding what you want at the right price are excellent. By contrast, what ailed the non-academic used-book market was poor liquidity—not enough sellers and buyers of an

unbounded

set of commodities. The result of too many products and not enough players was that the odds of finding what you want were poor. Thus, most buyers simply never consider a used-book store when they’re shopping for something specific.

Weatherford had realized that although the economics of each individual bookstore didn’t make a lot of sense, together (with all the bookstores combined or linked up) the overall used-book market made a

huge

amount of sense. The collective inventory of some 12,000 used-book stores could rival the best library in the world. The individual store owners uploaded their inventory, and Alibris collected them all together and ensured that the used books were displayed right alongside the new ones at the online booksellers that used Alibris data.

It made that database available to the big online booksellers such as Amazon and bn.com, which integrated the used-book listings alongside new books, effectively making “out of print” obsolete and offering a low-price alternative to new books. By bringing millions of customers to the used-book market, this gave used-book stores even more incentive to computerize their inventories, which, in turn, gave Alibris (and by extension its online retailing partners) even more inventory to sell. It was a classic virtuous circle, and the effect supercharged used-book sales. After years of stagnation, the $2.2 billion market is now growing

at double digits, with all that growth coming from a $600 million online market that’s growing by more than 30 percent a year, according to the Book Industry Study Group.

ENTER THE AGGREGATORS

Alibris is a Long Tail “aggregator”—a company or service that collects a huge variety of goods and makes them available and easy to find, typically in a single place. What it did by connecting the distributed inventories of thousands of used-book stores was to use information to create a liquid market where there was an illiquid market before. With a critical mass of inventory and customers, it tapped the latent value in the used-book market. And it did it at a tiny fraction of the cost that it would have required to assemble that much inventory from scratch, by outsourcing most of the work of assembling the catalog to the individual booksellers, who type in and submit the product listings themselves.

That’s the root calculus of the Long Tail: The lower the costs of selling, the more you can sell. As such, aggregators are a manifestation of the second force, democratizing distribution. They all lower the barrier to market entry, allowing more and more things to cross that bar and get out there to find their audience.

There are literally thousands of other examples, but I’ll give just a few here. Google aggregates the Long Tail of advertising (small-and medium-sized advertisers and publishers that make their money from advertising). Rhapsody and iTunes aggregate the Long Tail of music. Netflix does the same for the Long Tail of movies. EBay aggregates the Long Tail of physical goods and the Long Tail of merchants who sell them, right down to the millions of regular people getting rid of unwanted birthday presents.

It goes far beyond selling, too. Software, such as Bloglines, that collects “feeds” of online content using the RSS standard are also referred to as “aggregators,” and for good reason—they pull together and coherently order the Long Tail of online content, including millions of blogs. Wikipedia is an aggregator of the Long Tail of knowledge and those

who have it. The list of examples goes on and on, aggregating everything from ideas to people.

In this chapter, I’ll focus on the business aggregators. They fall mostly into five categories:

- Physical goods (e.g., Amazon, eBay)

- Digital goods (e.g., iTunes, iFilm)

- Advertising/services (e.g., Google, Craigslist)

- Information (e.g., Google, Wikipedia)

- Communities/user-created content (e.g., MySpace, Bloglines)

Each of these categories can range from massive companies to one-person operations. A single blog that collects all the news and information that it can about a topic, let’s say needlework, is an aggregator, as is Yahoo! Some aggregators attempt to straddle an entire category, such as Netflix (films) or iTunes (music), while others simply find their niche, such as services that aggregate only SEC filings or techno music.

Many aggregators occupy multiple categories. Amazon aggregates both physical goods (from electronics to cookware) and digital goods (from ebooks to downloadable software). Google aggregates information, advertising, and digital goods (Google Video). MySpace, the hugely popular networking site for bands and their fans, aggregates both content (millions of free songs) and the people who listen to it and, in turn, generates more content

about

those bands in the form of reviews, news, and other fan ephemera.

HYBRID VERSUS PURE DIGITAL

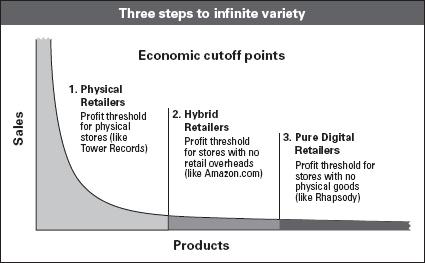

Let’s start by contrasting the first category of online aggregator businesses, selling physical goods online, with the second, selling digital goods online. They’re both Long Tail opportunities, but the second one can extend farther down the Tail than the first.

The online retailers of physical goods, from BestBuy.com’s camera selection to Netflix’s DVD library, can offer inventory hundreds of

times greater than their bricks-and-mortar counterparts, but eventually even they hit a limit. By contrast, the companies that sell digital goods, from albums or songs on iTunes to TV shows or amateur clips on Google Video, can theoretically go all the way down the Tail, expanding the variety they offer to encompass everything available. (The other three categories of aggregator—services, user-created content, and communities—are largely based on digital information, so they share this quality.)

We call the first type a

hybrid retailer

because it’s a cross between the economics of mail order (physical) and the Internet (digital). In this instance, the goods are usually delivered through the mail or FedEx, and the efficiencies come both in lowering the supply-chain costs with centralized warehouses and being able to offer an unlimited catalog with all the search and other informational advantages of a Web site.

Take Amazon’s CD business. It lists about 1.7 million CD titles. Combined with the collective inventories of its many third-party “marketplace” sellers, the total is probably closer to 2 million. Still, there are limits to that catalog.

Because CDs are physical items, somebody’s got to store them somewhere before they’re sold. As such, there’s some inventory risk associated with each Amazon listing. After all, a certain CD may never sell. Plus, there are shipping costs associated with each sale, so in practice, the price never falls below $3 or so. And, more important, the songs on a CD cannot be sold individually: it’s either the whole CD or nothing.

Clearly, Amazon’s CD economics are a whole lot better than the average record store’s, which is why it’s able to offer as much as one hundred times the choice. That takes Amazon well down the Tail. But not all the way. According to SNOCAP, a digital licensing and copyright management service that tracks the usage of peer-to-peer file-trading networks, there are at least 9 million tracks circulating online. That works out to nearly a million albums’ worth—and that doesn’t even include most music from before the age of CDs, much of which will eventually appear in digital form. Plus, there are many thousands

of garage bands and bedroom remixers who make music and distribute but have never released a CD at all. Together, all that music could easily amount to another million albums’ worth. So Amazon, despite all of its economic advantages, can actually get only a quarter of the way down the Long Tail of music (which is likely why they launched an MP3 download service in 2007).

The only way to reach all the way down the Tail—from the biggest hits down to all the garage bands of past and present—is to abandon atoms entirely and base all transactions, from beginning to end, in the world of bits. That’s the structure of the second class of aggregator, the pure digital retailer.

With the pure digital model, each product is simply a database entry, costing effectively nothing. The distribution costs are simply broadband megabytes, bought in bulk at fast-dropping costs incurred only when the product is ordered. What’s more, pure digital retailers can choose between selling goods as stand-alone products (ninety-nine-cent downloads at iTunes) or as a service (unlimited access music subscriptions at Rhapsody).

Those commercial digital services have all the advantages of Amazon’s online CD catalog, plus the additional savings of delivering their goods over broadband networks at virtually no cost. This is the way to achieve the holy grail of retail—near-zero marginal costs of manufacturing and distribution. Since an extra database entry and a few megabytes of storage on a server cost effectively nothing, these retailers have no economic reason not to carry everything available. And someday (once they get past messy issues such as rights clearance and contracts) they will.

Seen this way, there is no simple divide between traditional retailers and Long Tail ones. Instead, it’s a progression from the economics of pure atoms, to a hybrid of bits and atoms, to the ideal domain of pure bits. Digital catalogs of physical goods lower the economics of distribution far enough to get partway down the potential Tail. The rest is left to the even more efficient economics of pure digital distribution. Both are Long Tails, but one is potentially longer than the other.