The Long Tail (15 page)

Authors: Chris Anderson

This is why niches are different. One person’s

noise

is another’s

signal

. If a producer intends something to be absolutely right for one audience, it will, by definition, be wrong for another. The compromises necessary to make something appeal to everyone mean that it will almost certainly not appeal perfectly to anyone—that’s why they call it the

lowest common denominator

.

The remarkable consequence of the above graphic is that for many people, the best stuff is in the Tail. If you’re interested in audiophile stereo equipment, the finest gear is not going to be among the top-sellers at Best Buy. It will be too expensive, too complicated, and too hard to sell to the average customer. Instead, it’s going to be available at a specialist, and in overall sales ranking will be far down the Tail. Because this gear is so right for the audiophiles, it’s probably

not

right for people with less focused interests. Niche products are, by definition, not for everyone.

Down there in the low-selling side of the curve, there are also products that just aren’t very good. The challenge of filtering is to be able to tell one from the other. If you’ve got help—smart search engines, recommendations, or other filters—your odds of finding something just right for you are actually

greater

in the Tail. Best-sellers tend to appeal, at least superficially, to a broad range of taste. Niche products are meant to appeal strongly to a narrow set of tastes. That’s why the filter technologies are so important. They not only drive demand down the Tail, but they can also increase satisfaction by connecting people with products that are

more

right for them than the broad-appeal products at the Head.

THE TAIL THAT WAGS EVERYTHING ELSE

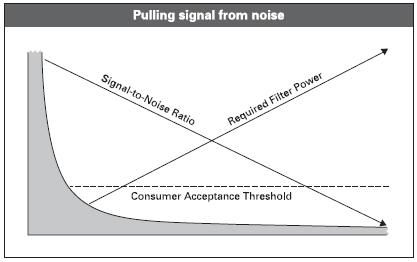

Another way to look at the situation is the graph below. As the Tail gets longer, the signal-to-noise ratio gets worse. Thus, the only way a consumer can maintain a consistently good enough signal to find what he or she wants is if the filters get increasingly powerful:

Why does the signal-to-noise ratio fall as you go down the Tail? Because there’s so much stuff there that what you’re looking for is over

shadowed by all the things you aren’t looking for. The reason for this is simple: The vast majority of everything in the world is in the Tail.

One of the consequences of living in a hit-driven culture is that we tend to assume that hits are a far bigger share of the market than they really are. Instead, they are the rare exception. This is what Nassim Taleb calls the “Black Swan Problem.”

The phrase comes from David Hume, the eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher, who gave it as an example of the complications that lie in deriving general rules from observed facts. In what has now become known as Hume’s Problem of Induction, he asked how many white swans one need observe before inferring that all swans are white and that there are no black swans. Hundreds? Thousands? We don’t know. (The Black Swan is not just a hypothetical metaphor: Until the discovery of Australia, common belief held that all swans were white. That belief was shattered with the sighting of the first

Cygnus atratus.

)

The problem is that we have a hard time putting rare events in context. In any given population there will be a few people who are tremendously rich. Some are smart and some are lucky and we really can’t tell which is which. In

Fooled by Randomness,

Taleb pokes fun at a bestseller called

The Millionaire Next Door,

which catalogs the investing tricks and work habits of multimillionaires, so that you can follow them and get rich, too. But as Taleb notes, random factors are just as likely to be responsible for that neighborly millionaire as investing strategies.

He defines a Black Swan as:

A random event satisfying the following three properties: large impact, incomputable probabilities, and surprise effect. First, it carries upon its occurrence a disproportionately large impact. Second, its incidence has a small but incomputable probability based on information available prior to its incidence. Third, a vicious property of a Black Swan is its surprise effect: at a given time of observation there is no convincing element pointing to an increased likelihood of the event.

He could just as easily be describing a blockbuster hit.

The reality is that the vast majority of content (from music to

movies) is not hits. Indeed, the vast majority of content is about as far from a hit as it’s possible to be, counting its audience in hundreds rather than millions. Sometimes that’s because it’s not very good. Sometimes it’s because it wasn’t marketed well or made by people with the right connections. And sometimes it’s because of some random factor that got in the way, which is just as likely as the random factors that sometimes make a blockbuster out of the flimsiest novelty fare (“Who Let the Dogs Out” comes to mind).

This is simply the natural consequence of what’s called a “powerlaw” distribution, a term for a curve where a small number of things occur with high amplitude (read: sales) and a large number of things occur with low amplitude. A few things sell a lot and a lot of things sell a little. (The phrase comes from the fact that the curve has a 1/

x

shape, which is the same as

x

raised to the–1 power.)

Since most stuff doesn’t sell very well, the volume of the material available—and by extension the volume of stuff you

don’t want

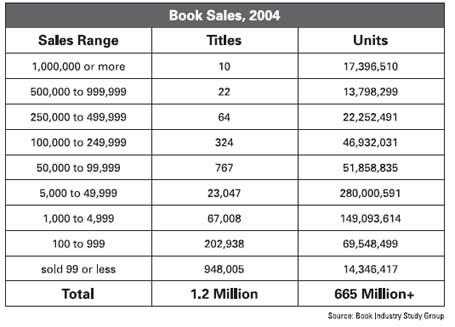

—rises as the Long Tail falls. Here’s some actual data from the book industry, showing the number of titles in each sales category for 2004:

The consequence of this is that whatever you

are

looking for, there’s more stuff you

aren’t

looking for the farther you go down the Tail. That’s why the signal-to-noise ratio gets worse, despite the fact that you’re often more likely (i.e., if you have access to good search and filters) to find what you want as you go down the Tail. It sounds like a paradox, but it isn’t. It’s just a problem for filters to solve.

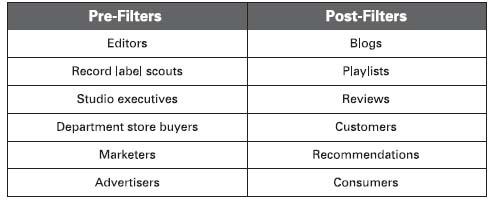

PRE-FILTERS AND POST-FILTERS

When you think about it, the world is already full of a different kind of filter. In the scarcity-driven markets of limited shelves, screens, and channels that we’ve lived with for most of the past century, entire industries have been created around finding and promoting the good stuff. This is what the A&R talent scouts at the record labels do, along with the Hollywood studio executives and store purchasing managers (“buyers”). In boardrooms around the world, market research teams pore over data that predicts what’s likely to sell and thus deserves to win a valuable spot on the shelf, screen, or page…and what’s unlikely to sell and therefore

doesn’t

deserve a spot.

The key word in the preceding paragraph is “predicts.” What’s different about those kinds of filters and the ones I’ve been focusing on is that they filter

before

things get to market. Indeed, their job is to decide what will make it to market and what won’t. I call them “pre-filters.”

By contrast, the recommendations and search technologies that I’m writing about are “post-filters.” The post-filters find the best of what’s already out there in their area of interest, elevating the good (i.e., what is relevant, interesting, original, etc.) and downplaying, even ignoring, the bad. When I talk about throwing everything out there and letting the marketplace sort it out, these post-filters are the voice of the marketplace. They channel consumer behavior and amplify it, rather than trying to predict it.

Here, in table form, are some examples of each:

The fact that post-filters amplify, rather than predict, behavior is an important distinction. In the existing Short Head markets, where distribution is expensive and shelf space is at a premium, the supply side of the market has to be exceedingly discriminating in what it lets through. These producers, retailers, and marketers have made a science of trying to guess what people will want, to improve their odds of picking winners. Obviously they don’t always guess right. There are surely as many things that deserved to make it to market but were overlooked as there are things that made it to market and then flopped. Nevertheless, the survivors obtain a credible reputation for having some sort of mystical insight into the consumer psyche.

However, in Long Tail markets—where distribution is cheap and shelf space is plentiful—the safe bet is to assume that

everything

is eventually going to be available.

As such, in Long Tail markets, the role of filter then shifts from gatekeeper to advisor. Rather than

predicting

taste, post-filters such as Google

measure

it. Rather than lumping consumers into predetermined demographic and psychographic categories, post-filters such as Netflix’s customer recommendations treat them like individuals who reveal their likes and dislikes through their behavior. Rather than keeping things off the market, post-filters such as MP3 blogs

create

a market for things that are already available by stimulating demand for them. Jeff Jarvis calls this the difference between “first-person and third-person markets.”

In general, blogs are shaping up to be a powerful source of influen

tial recommendations. There are independent enthusiast sites such as PVRblog and Horticultural (an organic gardening blog), commercial blogs such as Gizmodo and Joystiq, and then the random recommendations of whichever blogger you happen to read for any reason. (There does seem to be a natural connection between mavens, who know a lot and like to share their knowledge, and blogging.) What they may lack in polish and scope, they more than make up in

credibility:

Their readers know that there is a real person there that they can trust.

Of course, just as pre-filters aren’t perfect—e.g., the talent scouts don’t always pick artists that sell records—the same is true of post-filters. Because post-filters tend to be amateurs, oftentimes that means less critical independence and more random malice. Moreover, the problem with post-filtering is that feedback comes

after

publication, not before. As a result, errors that would have been caught by editors and other wise eyes can sneak through, and even though the collective post-filter feedback can eventually correct them, they may never disappear entirely.

Interestingly, when I consider my own role, I find that I do both. As the editor of a magazine with a finite number of pages, I’m a classic pre-filter. I indulge in all sorts of brutal discrimination and guesswork to decide which articles to run. But

Wired

also does lots of product reviews, and in that respect, we’re a post-filter. We look at the universe of what’s already out there and bring the best stuff to our readers’ attention.