The Long Tail (17 page)

Authors: Chris Anderson

This is why I’ve described the Long Tail as the death of the 80/20 Rule, even though it’s actually nothing of the sort. The real 80/20 Rule is just the acknowledgment that a Pareto distribution is at work, and some things will sell a lot better than others, which is as true in Long Tail markets as it is in traditional markets.

What the Long Tail offers, however, is the encouragement to not be dominated by the Rule. Even if 20 percent of the products account for 80 percent of the revenue, that’s no reason not to carry the other

80 percent of the products. In Long Tail markets, where the carrying costs of inventory are low, the incentive is there to carry everything, regardless of the volume of its sales. Who knows—with good search and recommendations, a bottom 80 percent product could turn into a top 20 percent product.

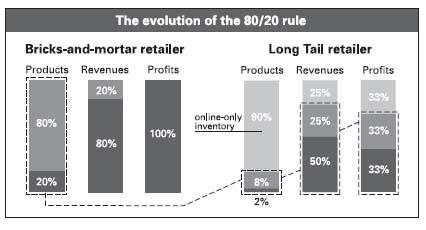

Because a traditional bricks-and-mortar retailer has significant inventory costs, products that don’t sell well tend to be unprofitable. Thus, virtually all the profit comes from the 20 percent that do sell well. I’ve shown that in the top part of the graphic below, which gives an idealized case for a hypothetical bricks-and-mortar retailer:

For a Long Tail retailer, however, the picture is very different. First, let’s assume it has ten times as much inventory, so in this hypothetical example the 20 percent of products that make up most of the revenues of the first retailer become just 2 percent of the Long Tail retailer’s inventory, as per the bottom left bar in the graphic above.

The revenue picture, in the second bar, reflects the natural consequences of a powerlaw distribution. The top 2 percent of products still account for a disproportionate share of the sales, in this case 50 percent. The next 8 percent of products account for the next 25 percent of sales. And the bottom 90 percent of products account for the remaining 25 percent of sales. (Although this is just a hypothetical example, those numbers are quite close to the actual statistics from both Rhapsody and Netflix.)

Where Long Tail economics really shines, however, is in the third bar, profits: Because of the low cost of inventory, the margins for non-hits can be far higher in Long Tail markets than in traditional bricks-and-mortar.

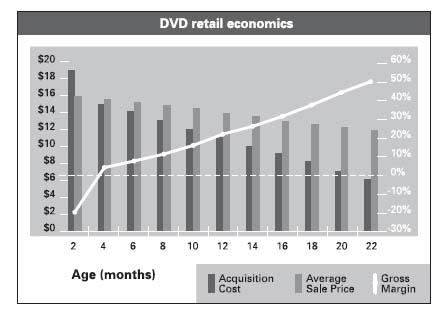

Let’s use DVDs as an example. The chart below gives a rough sense of DVD economics for a retailer such as Wal-Mart:

What you see here is that the economics of new releases these days is simply awful. The studios charge $17–$19 for the DVDs and the “big box” retailers (Wal-Mart, BestBuy) sell them for $15–$17 for the first week or two, for an average loss of $2 per DVD. (This is before overheads; the actual loss is larger.)

After the first month or so, the wholesale price (what the distributors charge the stores) of the DVDs goes down faster than the retail price (what the stores charge us), and they gradually become profitable to sell. Yet nearly 80 percent of the sales for DVD retailers are of titles within their first two months of release, before they’ve moved significantly into profitability. Why do stores sell new releases so cheaply? Because for the big-box retailers, at least, they’re a loss leader, de

signed to draw people to other titles in the DVD section or items elsewhere in the store, where the margins are better. DVD distributors encourage this by allowing unsold new releases to be returned, lowering the risk for retailers.

The problem is that while this makes sense for the big-box retailers who have other things to sell, it has the effect of also setting the price for everyone else, including the specialty DVD retailers like Blockbuster. The big-box retailers have thus driven down the margins for new releases across the industry, making the economics of the Head even tougher. No wonder Blockbuster is struggling.

But if you could shift demand farther into the Tail, creating a market that wasn’t so dependent on new releases, you could improve the profit picture immensely. As you can see in the graphic on the previous page, the older the title the more profitable it is. That’s why Long Tail retailers have such an advantage—they have the shelf space to carry the older titles. This is also why recommendations and other filters are so important to Long Tail markets. By encouraging people to venture from the hits world (high acquisition costs) to the niche world (low acquisition costs), smart retailers have the potential to improve the economics of retail dramatically. (This is, by the way, exactly what Netflix does: It underbuys new releases—despite the fact that such unavailability and delay annoys some customers and increases churn—because that allows Netflix to maintain its margins.)

The above explains why the Long Tail profit bar in the graph on chapter 8 shows a more even distribution of profit than of revenues. Long Tail products may not account for most of the sales, but because they’re often cheaper to acquire, they can be very profitable, as long as inventory costs are kept close to zero. So the 80/20 Rule changes in three ways in Long Tail markets:

- You can offer

many

more products. - Because it is so much easier to find these products (thanks to recommendations and other filters), sales are spread more evenly between hits and niches.

- Because the economics of niches is roughly the same as hits, there are profits to be found at

all

levels of popularity.

While the 80/20 Rule is still alive and well, in a Long Tail market it has lost its bite.

DOES A LONGER TAIL MEAN A SHORTER HEAD?

One of the main questions that came up as I got deeper into quantifying Long Tail markets was about the effect of increased variety on the overall shape of the demand curve. As aggregators are able to carry more and more products, lengthening their Tail, will the relatively few hits at the Head sell less? More? The same?

There are three aspects of the Long Tail that have the effect of shifting demand down the tail, from hits to niches. The first is the availability of greater variety. If you offer people a choice of ten things, they will choose one of the ten. If you offer them a thousand things, demand will be less concentrated in the top ten.

The second is the lower “search costs” of finding what you want, which range from actual search to recommendations and other filters. Finally, there is sampling, from the ability to hear thirty seconds of a song for free to the ability to read a portion of a book online. This tends to lower the risk of purchasing, encouraging consumers to venture farther into the unknown.

There are several ways to try to quantify this with hard data. One is to compare a market that offers relatively limited variety with one that offers much more variety of the same sort of products. Another is to track a Long Tail aggregator/retailer over time, watching what happens as its inventory grows. Yet another would be to just look at the effect of lowered search costs online, making an apples-to-apples comparison with a similar offline inventory.

A 2005 study by a team at MIT lead by Erik Brynjolfsson, who did some of the early work on Amazon’s Long Tail inventory, looked at this effect at a women’s clothing retailer. The company has a catalog busi

ness and an online business, both of which offer the exact same inventory and prices. The difference is that online, it has search, easy browsing of both products and variations of those products, and ways to organize the offerings using “rank by” filters.

The result was that consumers—even those that shopped in both the catalog and online—tended to buy farther down the Tail online. The bottom 80 percent of products accounted for 15.7 percent of catalog sales, but 28.8 percent of online sales. Or to switch it around and see it from the top 20 percent perspective, the catalog exhibited an 84/20 rule, while the online site was closer to 71/20.

That’s the effect of lowered search costs for the same inventory. To measure the effect of different inventories—one much larger than the other—we worked to construct an apples-to-apples comparison between a retailer with limited shelf space and one with unlimited shelf space. In practice, that means comparing a bricks-and-mortar store with an online one selling or renting the same things. We decided to use entertainment examples because the online markets were mature enough to measure with confidence and the data was available. We looked at both music and DVDs.

Rather than pick a single bricks-and-mortar retailer, we used industry-wide data compiled by Nielsen divisions—SoundScan for music and DVDScan for movies. We compared that with online data from Rhapsody and Netflix, respectively.

(There are several corrections required to do these comparisons properly. In music we had to find a way to compare album sales offline with track sales online, and then from individual sales to streams under a subscription plan. In DVDs it was a matter of comparing sales and single-copy rental data offline with subscription rental online. Although the methodologies are beyond the scope of this book, they broadly revolve around using other data sets, such as pay-per-track online sales, to calibrate the curves and eliminate as many systematic biases as we could.)

After the corrections, the results were striking: The online demand curve is much flatter. The average niche music album title—those beyond the top 1,000—sold about twice as well online than offline. And

the average niche DVD—again those beyond the top 1,000—was

three

times as popular online as it was offline.

Another way to look at this is to see how much less dominated the online market is by the top hits. Here’s the data for music. Offline, in bricks-and-mortar retailers, the top 1,000 albums make up nearly 80 percent of the total market. (Indeed, in a typical big-box retailer, which carries just a fraction of available CDs, the top 100 albums can account for more than 90 percent of the sales.) By contrast, online that same top 1,000 accounts for less than a third of the market. Seen another way, a full half of the online market is made up of albums

beyond

the top 5,000.

DOES THE LONG TAIL INCREASE DEMAND OR JUST SHIFT IT?

Does the Long Tail grow the pie or simply slice it differently? In other words, as the number of available products grows many-fold with the infinite shelf space of virtual retailers, does it encourage people to buy more stuff or just less popular stuff? In general, the answer depends on the sector: Some do seem to have huge opportunities for growth as their niches become widely available, and some do not.

Although human attention and spending power are finite, you can get

more

for your time and money. Some forms of entertainment, such as music, are “non-rivalrous” for attention, which is to say you can consume them while you’re doing something else. For instance, some explanations for the rise of average hours of TV watching in the seventies and eighties involved the idea that a generation had grown up used to television on in the background of their lives; as the novelty wore off, it went from a rivalrous to a non-rivalrous medium, and thus we consumed more of it.

Other media, such as text, may not be consumed faster, but they can be consumed more efficiently and with greater satisfaction through better preselection. Indeed, it’s quite extraordinary how much we’ve been able to increase our consumption bandwidth of information, scanning pages of Google search results and custom blog feeds. I may not read

any more words than I once did, but they’re more likely to be meaningful to me, thanks to much better filters (better at suiting my own interests than, say, the editors of any newspaper) preselecting what I do read. So because the words are more relevant, my meaningful bandwidth has increased; I have, in a sense, compressed my reading attention.

But once you combine the scarcity of disposable income with the scarcity of time, some non-rivalrous media may become rivalrous. The reason people have the television on in the background is that it doesn’t cost them anything to do so. But if that were pay-per-view video, you can bet it would suddenly become the center of their attention. From a consumer perspective, this highlights the advantages of all-you-can eat subscription services, which offer risk-free exploration down the Tail. You’re likely to consume more if it doesn’t cost you more to do so.