The Long Tail (16 page)

Authors: Chris Anderson

As long as there’s a market for a pre-filtered package in the deliciously finite medium of bound glossy paper, I suspect there will continue to be demand for my old-fashioned discriminatory side. But the day when people like me decide what makes it to market and what doesn’t is fading. Soon everything will make it to market and the real opportunity will be in sorting it all out.

SCARCITY, ABUNDANCE, AND THE DEATH OF THE 80/20 RULE

In the summer

of 1897 an Italian polymath named Vilfredo Pareto busied himself in his university office in Switzerland, studying patterns of wealth and income in nineteenth-century England. It was the age of Marx, and the question of wealth distribution was in the air. Pareto found that the spread of wealth was indeed unequal in England—most of it went to a minority of the people. When he calculated the exact ratios, he found that about 20 percent of the population owned 80 percent of the wealth. More important, when he compared that with other countries and regions, he found that the ratio remained the same.

What Pareto had discovered is that there is a predictable mathematical relationship in the patterns of wealth and populations, something he called the Law of the Vital Few. It seemed constant over time, and across countries. Pareto was a brilliant economist, but he was a poor explainer, so not many understood the importance of his insight. He went on to write obscure sociological tracts about elites, which unfortunately were taken up at the end of his life by Mussolini’s fascists. But the theory of unequal distribution took on a life of its own, and Pareto’s observation is now known as the 80/20 Rule.

In 1949, George Zipf, a Harvard linguist, found a similar principle at work in words. He observed that while a few words are used very often, many or most are used rarely. Although that’s not surprising, what Zipf also observed was that that relationship was entirely predictable, and indeed was the same as Pareto’s wealth curve. The frequency with which a word was used was proportional to 1 divided by the word’s frequency rank among all words. This means that the second item occurs approximately

1

/2 as often as the first, and the third item

1

/3 as often as the first, and so on. This is now called Zipf’s Law.

The same is true, Zipf found, for a host of other phenomena, from population statistics to industrial processes. He analyzed Philadelphia marriage licenses within one twenty-block area and showed that 70 percent of the marriages were between people who lived no more than 30 percent of that distance apart.

Since then, other researchers have extended the rule to everything from atoms in a plasma to the size of cities. At the heart of these observations is the ubiquity of powerlaw distributions, the 1/

x

shape that Pareto first saw in his wealth curves.

Powerlaws are a family of curves that you can find practically anywhere you look, from biology to book sales. The Long Tail is a powerlaw that isn’t cruelly cut off by bottlenecks in distribution such as limited shelf space and available channels. Because the amplitude of a powerlaw approaches but never reaches zero as the curve stretches out to infinity, it’s known as a “long-tailed” curve, which is where I derived the name of this book.

As far as consumer markets go, powerlaws come about when you have three conditions:

- Variety (there are many different sorts of things)

- Inequality (some have more of some quality than others)

- Network effects such as word of mouth and reputation, which tend to amplify differences in quality

In others words, powerlaw distributions occur where things are different, some are better than others, and effects such as reputation can work to promote the good and suppress the bad. This results in what

Pareto called the “predictable imbalance” of markets, culture, and society: Success breeds success. Needless to say, these forces describe a good fraction of the world around us.

HOW DISTRIBUTION BOTTLENECKS DISTORT MARKETS

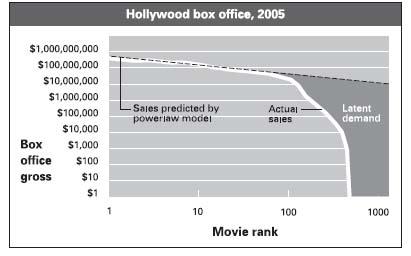

To see what happens to powerlaws in the real world, let’s look at the example of Hollywood box office. If you plot the data the usual way, it’s the familiar shape: A few blockbusters dominate the high part of the curve at the left and a vast population of others (non-hits, to use the least pejorative term) account for the low part at the right.

Because all powerlaws tend to look alike when plotted like this, it’s often useful to put them on a scale that shows their differences more clearly. One way to do that is to graph them on a logarithmic scale, where each division is a factor of 10 larger than the one that came before it: 10, 100, 1,000, and so on. (Common examples of logarithmic scales are the Richter scale of earthquakes and the decibel scale of sound volume.)

When you plot a proper powerlaw on a log scale on both axes (called a “log-log graph”), you should get a straight line sloping down. The exact angle of that slope varies from market to market, but whether it’s the sales of soup or the distribution of publicly listed companies by stock-market capitalization, the natural shape of a market is a straight line.

But all too often in the real world, it doesn’t look like that at all. Instead, the curve starts off as a straight line and then simply dies. In our box office case, that looks like the curve on chapter 8.

Notice what happens around rank 100. Box-office revenues fall sickeningly until they approach zero at around 500. (In fact, the lowest recorded box office of the year was $423 for

The Dark Hours

, a Canadian horror film made on a shoestring budget with a cast of unknowns. According to those who have seen it, it’s actually not bad at all.)

What happened? Did the movies suddenly get worse at rank 100? Did they stop making movies after the first 500? Or is that heart-stopping fall just a measurement error?

Sadly, here’s your answer:

None of the above.

It’s not a measurement error. The movies don’t get worse at rank 100 (some would argue they actually get better). And they didn’t stop making movies at 500. Indeed, an estimated 13,000 feature films are shown in festivals each year in the United States alone, and that doesn’t include the tens of thousands of foreign films not shown in the United States.

What happened is that the films past the first 100 or so simply failed to get much theatrical distribution. Or, to put it another way, the “carrying capacity” of the U.S. theatrical industry is only about 100 films a year. The economics of local movie theaters are cruel and unforgiving. It’s not enough that a film be good or big in Bombay. It’s got to be big enough in Stamford, Connecticut, or wherever else a theater happens to be, to pull more than a couple thousand people through the door over a two-week run. Typically, that necessitates a big marketing budget, a distribution deal, and probably a star or two—if you can afford them.

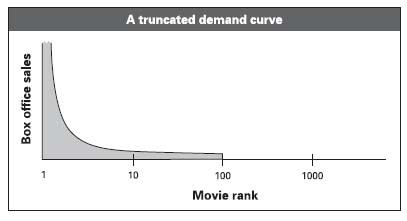

Movies that don’t have all that don’t make it to the big theater chains. In effect, these chains lop off the consumer supply of films at the point where the economics stop making sense. They simply truncate the curve. Filmmakers don’t stop making movies there, of course; a phantom line keeps going along the curve past the cutoff point, marking the box office sales that these other films would have earned if they had

only gotten distribution. In the “real world,” however, those films disappear from the commercial mainstream. Simply put, they don’t make the cut. What should be a Long Tail instead looks roughly like this:

Granted, it’s not quite as bad as I’m making it out to seem. If they’re lucky, a few of the really good films that knocked out audiences at Sundance do get picked up by a few repertory houses in college towns. That, mostly likely, is the group that accounts for the 100–500 line on chapter 8, the members of which have low—but not quite zero—revenues. And the rest—the 500 to at least 13,000? Well, sadly most of them garnered no theatrical distribution at all. And if they’re not seen in a theater, they have no box-office gross. This means that from the perspective of the earlier chart they just don’t exist.

Of course, they do exist. It’s just that they don’t show up in the charts of an industry that judges merit through a box-office lens. Where do these other movies go? Most of them are never seen outside of film festivals and private showings. Some of them make it to TV or DVD if their makers can clear the rights to the music and get other necessary permissions. Others might be distributed for free online.

That sounds pretty bleak, but some of those derided nontheatrical distribution channels, such as direct-to-DVD and the Internet, are starting to become major markets in their own right. TV shows on DVD are by far the fastest growing part of the DVD business. And the

market for video delivery over the Internet, while still just taking shape, may become bigger yet. With box office shrinking and DVD sales and retail growing, theatrical release is no longer the only worthwhile path to market.

The lesson is that what we thought was a naturally sharp drop-off in demand for movies after a certain point was actually just an artifact of the traditional costs of offering them. In other words, give people unlimited choice and make it easy for them to find what they want, and you discover that demand keeps on going into niches that were never even considered before—instructional videos, karaoke, Turkish TV, you name it. Netflix changed the economics of offering niches and, in doing so, reshaped our understanding about what people actually

want

to watch.

The same is true for virtually every other market you can imagine. In books, Barnes & Noble found that the bottom 1.2 million titles represent just 1.7 percent of its in-store sales, but a full 10 percent of its online (bn.com) sales. PRX, which licenses a huge library of public radio programming online, reports that the bottom 80 percent of its content now accounts for half of its sales. And in India, rediff.com, one of the largest Web portals and ringtone providers, saw what happened as ringtone demand shifted from being driven by Top 20 lists published in newspapers to an online business driven by search. The top 20 ringtones, which had accounted for 80 percent of sales in the newspaper era, fell to just 40 percent when users could search online from a catalog that now has nearly 20,000 songs.

Music shows some of the most dramatic effects. In traditional retail, new album releases accounted for 63 percent of sales in 2005; the rest were older “catalog” albums, according to Nielsen SoundScan. Online, that percentage is reversed: New music accounts for about a third of sales and older music accounts for two-thirds.

THE 80/20 RULE

The best known manifestation of Pareto/Zipf distributions is the 80/20 Rule, which is often used to explain that 20 percent of products ac

count for 80 percent of revenues, or 20 percent of our time accounts for 80 percent of our productivity, or any number of other comparisons that all share this characteristic of a minority having disproportionate impact.

The 80/20 Rule is chronically misunderstood, for three reasons. First, it’s almost never exactly 80/20. Most of the large-inventory markets I’ve studied are 80/10 or even less (no more than 10 percent of products account for 80 percent of sales).

If you’re troubled by the fact that 80/10 doesn’t add up to 100, you’ve discovered the second confusing thing about the Rule. The 80 and the 20 are percentages of

different things,

and thus don’t need to equal 100. One is a percentage of products, the other a percentage of sales. Worse, there’s no standard convention on how to express the relationship between the two, or which variable to hold constant. Saying a market has an 80/10 shape (10 percent of products account for 80 percent of sales) can be the same as saying it’s 95/20 (20 percent of products account for 95 percent of sales).

Finally, the Rule is misunderstood because people use it to describe different phenomena. The classic definition is about products and revenues, but the Rule can just as equally be applied to products and

profits

.

One of the most pernicious misinterpretations is to assume that the 80/20 Rule is an invitation to carry

only

the 20 percent of goods that account for the most sales. This derives from the observation that the 80/20 Rule is fundamentally an encouragement to be discriminating in what you carry, because if you guess right, the product can have a disproportionate effect on your business.