The Long Tail (14 page)

Authors: Chris Anderson

Yet another limitation is that many kinds of recommendations tend to be better for one genre than for another—rock recommendations aren’t useful for classical and vice versa. In the old hit-driven model, one size fit all. In this new model, where niches and sub-niches are abundant, there’s a need for specialization. An example of this is iTunes, which, for all of its accomplishments, shows a pop-music bias that undermines its usefulness for other kinds of music.

In iTunes and services like it different genres—such as rock, jazz, or classical—are all displayed in a similar way, with the main classification scheme being “artist.” But who is the “artist” for classical—the composer, the orchestra, or the conductor? Is a thirty-second sample of a concerto meaningful? In the case of jazz, you may be more inter

ested in following the careers of the individual performers, rather than the band, which may have come together only for a single album. Or perhaps you’re more interested in the year, and would like to find other music that came out at the same time. In all these cases, you’re out of luck. The iTunes software won’t let you sort by any of those.

These are the failures of one-size-fits-all aggregation and filtering. ITunes may be working its way down the Tail, but its emphasis on simplicity—and lowest-common-denominator metadata—forces it into a standard presentational model that can’t cater effectively to every genre—and therefore, every consumer. And this is not to pick just on iTunes—the same is true for every music service out there.

Because no one kind of filter does it all, listeners tend to use many of them. You may start your exploration of new music by following a recommendation, then once it’s taken you to a genre you like, you may want to switch to a genre-level top ten list or browse popular tracks. Then, when you’ve found a band you particularly like, you might explore bands that are like it, guided by the collaborative filters. And when you come back a week later and find that nothing’s changed, you’ll need another kind of filter to take you to your next stop on your exploration. That could be a playlist—catching a magic carpet ride on someone else’s taste—which can take you to another genre, where you can settle in and start the process again.

NOT ALL TOP TEN LISTS ARE CREATED EQUAL

Not long ago, there were far fewer ways to find new music. Aside from personal recommendations, there were editorial reviews in magazines, perhaps the advice of a well-informed record store clerk, and the biggest of them all, radio airplay. Radio playlists, especially today, are the prime example of the best-known filter of all, the popularity list. The Top 10, 40, and 100 are the staples of the hit-driven universe, from Nielsen ratings to the

New York Times

book best-seller list. But in a Long Tail world, with so many other filters available, the weaknesses of Top 10 lists are becoming more and more clear.

There’s nothing wrong with ranking by popularity—after all, that’s

just another example of a “wisdom of crowds” filter—but all too often these lists lump together all sorts of niches, genres, subgenres, and categories into one unholy mess.

A case in point: blogs. As I write, Technorati lists the top ten blogs as:

- BoingBoing: A Directory of Wonderful Things

- Daily Kos: State of the Nation

- Drew Curtis’ FARK.com

- Gizmodo: The Gadgets Weblog

- Instapundit.com

- Engadget

- PostSecret

- Talking Points Memo: by Joshua Micah Marshall

- Davenetics Politics Media Musings

- dooce

What have we learned? Well, not much. There are a couple of gadget blogs in the list, two or three political blogs, some uncategorizable subculture ones (BoingBoing, FARK, PostSecret), and a personal blog (dooce).

These lists are, in other words, a semi-random collection of totally disparate things.

To use an analogy, top-blog lists are akin to saying that the best-sellers in the supermarket today were:

- DairyFresh 2% vitamin D milk

- Hayseed Farms mixed grain bread

- Bananas, assorted bunches

- Crunchios cereal, large size

- DietWhoopsy, 12-pack, cans

- and so on…

Which is pointless. Nobody cares if bananas outsell soft drinks. What they care about is which soft drink outsells which

other

soft drink. Lists make sense only in context, comparing like with like within a category.

My take: This is another reminder that you have to treat niches as niches. When you look at a widely diverse three-dimensional marketplace through a one-dimensional lens, you get nonsense. It’s a list, but it’s a list without meaning. What matters is the rankings

within

a genre (or subgenre), not

across

genres.

Let’s take this back to music. As I write, the top ten artists on Rhapsody overall are:

- Jack Johnson

- Eminem

- Coldplay

- Fall Out Boy

- Johnny Cash

- Nickelback

- James Blunt

- Green Day

- Death Cab for Cutie

- Kelly Clarkson

Which is, as I count it, two “adult alternative,” one “crossover/hiphop,” one “Brit-rock,” one “emo,” one “outlaw country,” one “post-grunge,” one “punk-pop,” one “indie-rock,” and one “teen beat.” Does anybody care if outlaw country outsells teen beat this week or vice versa? Does this list help anyone who is drawn to any of these categories find more music they’ll like? Yet the Top 10 (or Top 40, or Top 100) list is the lens through which we’ve looked at music culture for nearly half a century. It’s mostly meaningless, but it was all we had.

Let’s contrast that with a different kind of top ten list, that for the music subgenre Afro-Cuban jazz:

- Tito Puente

- Buena Vista Social Club

- Cal Tjader

- Arturo Sandoval

- Poncho Sanchez

- Dizzy Gillespie

- Perez Prado

- Ibrahim Ferrer

- Eddie Palmieri

- Michel Camilo

Now

that’s

a top ten list. It’s apples-to-apples and thus useful from top to bottom. Such lists are possible because we have abundant information about consumer preference and enough space for an infinite number of top ten lists—there doesn’t have to be just one. In this case Tito Puente is number one in a very niche category—a big fish in a small pond. For people into this genre, this is a big deal indeed. For those who aren’t, he’s simply another obscure artist and safely ignored. Tito Puente’s albums don’t rise to the top of the overall music charts—they’re not blockbusters. But they do dominate their category, creating what writer Erick Schonfeld calls “nichebusters.” Filters and recommendations work best at this scale, bringing the mainstream discovery and marketing techniques to micromarkets.

IS THE LONG TAIL FULL OF CRAP?

Why are filters so important to a functioning Long Tail? Because without them, the Long Tail risks just being noise.

The field of “information theory” was built around the problem of pulling coherent signals from random electrical noise, first in radio broadcasts and then in any sort of electronic transmission. The notion of a signal-to-noise ratio is now used more broadly to refer to any instance where clearing away distraction is a challenge. In a traditional “Short Head” market this isn’t much of a problem, because everything on the shelf has been prefiltered to remove outliers and other products far from the lowest common denominator. But in a Long Tail market, which includes nearly everything, noise can be a huge problem. Indeed, if left unchecked, noise—random content or products of poor quality—can kill a market. Too much noise and people don’t buy.

The job of filters is to screen out that noise. Call it pulling wheat

from chaff or diamonds from the rough, the role of a filter is to elevate the few products that are right for whoever is looking and suppress the many that aren’t. I’ll explain this by considering one commonly held misperception.

One of the most frequent mistakes people make about the Long Tail is to assume that things that don’t sell well are “not as good” as things that do sell well. Or, to put it another way, they assume that the Long Tail is full of crap. After all, if that album/book/film/whatever were excellent, it would be a hit, right? Well, in a word, no.

Niches operate by different economics than the mainstream. And the reason for that helps explain why so much about Long Tail content is counterintuitive, especially when we’re used to scarcity thinking.

First, let’s get one thing straight:

The Long Tail is indeed full of crap.

Yet it’s also full of works of refined brilliance and depth—and an awful lot in between. Exactly the same can be said of the Web itself. Ten years ago, people complained that there was a lot of junk on the Internet, and sure enough, any casual surf quickly confirmed that. Then along came search engines to help pull some signal from the noise, and finally Google, which taps the wisdom of the crowd itself and turns a mass of incoherence into the closest thing to an oracle the world has ever seen.

This is not unique to the Web—it’s true everywhere. Sturgeon’s Law (named after the science fiction writer Theodore Sturgeon) states that “ninety percent of everything is crud.” Just think about art, not from the perspective of a gallery but from a garage sale. Ninety percent (at least) is crud. And the same is true for music, books, and everything else. The reason we don’t think of it that way is that most of it is filtered away by the scarcity sieve of commercial retail distribution.

On a store shelf or in any other limited means of distribution, the ratio of good to bad matters because it’s a

zero sum game:

Space for one eliminates space for the other. Prominence for one obscures the other. If there are ten crappy toys for each good one in the aisle, you’ll think poorly of the toy store and be discouraged from browsing. Likewise it’s no fun to flip through bin after bin of CDs if you haven’t heard of any of them.

But where you have unlimited shelf space, it’s a

non-zero sum game.

The billions of crappy Web pages about whatever are not a problem in the way that billions of crappy CDs on the Tower Records shelves would be. Inventory is “non-rivalrous” on the Web and the ratio of good to bad is simply a signal-to-noise problem, solvable with information tools. Which is to say it’s not much of a problem at all. You just need better filters. In other words, the noise is still out there, but Google allows you to effectively ignore it. Filters rule!

This leads to the key to what’s different about Long Tails. They are

not

prefiltered by the requirements of distribution bottlenecks and all those entail (editors, studio execs, talent scouts, and Wal-Mart purchasing managers). As a result their components vary wildly in quality, just like everything else in the world.

One way to describe this (using the language of information theory again) would be to say that Long Tails have a

wide dynamic range

of quality: awful to great. By contrast, the average store shelf has a relatively

narrow dynamic range

of quality: mostly average to good. (There’s some really great stuff, but much of that is too expensive for the average retail shelf; niches exist at both ends of the quality spectrum.)

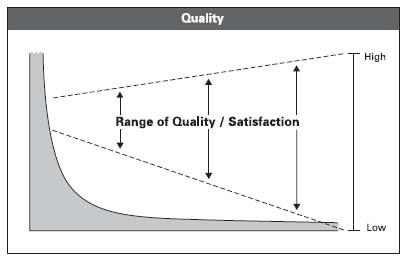

So tails have a wide dynamic range and heads have a narrow dynamic range. Graphically, that looks like this:

It’s crucial to note that there are high-quality goods in every part of the curve, from top to bottom. Yes, there are more low-quality goods in the tail and the average level of quality declines as you go down the curve. But with good filters, averages don’t matter. Diamonds can be found anywhere.

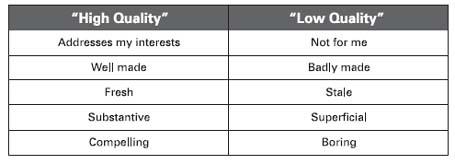

To clarify, here are some examples of criteria people might use to evaluate content.

Obviously, the terms “high quality” and “low quality” are entirely subjective, so all of these criteria are in the eye of the beholder. Thus, there are no absolute measures of content quality. One person’s “good” could easily be another’s “bad”; indeed, it almost always is.