The Mapmaker's Wife (15 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

Q

UITO IS BUILT ON

the lower slopes of Mount Pichincha, a volcano that has often rained ashes down on the homes below. The landscape is also cut by two deep ravines carrying waters tumbling down from Pichincha, which, in the 1700s, was covered with snow and ice. Such topography makes it an unlikely place for a city, and yet, as the members of the French expedition quickly sensed, there was something special, even spiritual, about this spot. Upon his arrival, Bouguer called it a

“tropical paradise,” and at every step they were confronted with evidence of its long history. Barefoot Indians trotted through the city, the men dressed in white cotton pants and a black cotton poncho, and they greatly outnumbered those of Spanish blood.

As far back as the fifth century

A.D

., Indians had come to this spot to trade goods, with gold, silver, and pearls the treasured items of the day. The people in this region came to be known as the Quitus. In the eleventh century, a tribe living along the coast, the Caras, ascended the Esmeraldas River into the valley, intermarrying

with the Quitus, and collectively the two groups came to be known as the Shyri Nation. Two centuries later, the Shyris intermarried with the Puruhás to the south, forming the peaceful Kingdom of Quitu. The people worshipped the sun and built an observatory to study the solstices.

Around 1470, the Incas, led by the great warrior Tupac Yupanqui, began their conquest of this kingdom, capturing the city of Quitu in 1492. They brought with them a language, Quechua, which they made the common tongue of the realm, and for the next thirty-five years, during the reign of Huayna Capac, the Inca Empire prospered, with Quito its northern capital. Huayna Capac died in 1525, and after his son Atahualpa was killed by Pizarro at Cajamarca in 1533, one of Pizarro’s men, Sebastián de Benalcázar, marched north to lay claim to Quito. He entered Quito in December 1534, with 150 horsemen and an infantry of eighty, but found it deserted and in ruins. Rumiñahui, a local Indian chieftain who had remained loyal to the Incas, had torched the city rather than hand it over to the Spaniards.

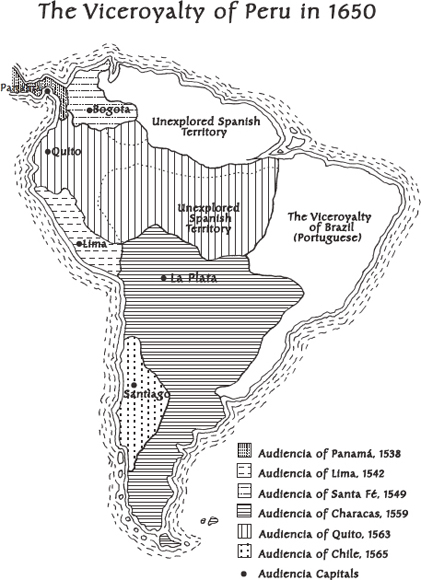

Benalcázar founded the new village of San Francisco de Quito atop the ashes of the old. As was their custom, the Spaniards plotted out a blueprint for their city, locating the

plaza mayor

close to the old Indian marketplace. In 1563, Spain made Quito the capital of the Audiencia de Quito, a jurisdictional district that stretched more than 1,500 miles north to south and 500 miles east to west. As a capital, Quito was home to all the fixtures of colonial government—an administrative palace, a judicial court, and a royal treasury. By the early eighteenth century, it could also boast of three colleges and a hospital (founded in the sixteenth century), and it was famous throughout Peru for its elaborate cathedrals.

The people of Quito had been waiting for the arrival of the French expedition for months, for Philip V’s letter, in which he urged his representatives to treat the visitors well, had reached them on September 10, 1735 (thirteen months after it was written). No one had been quite sure what to expect—after all, the city had never hosted a group of foreigners before, and these men were said

to be the great minds of Europe—so when Godin and the others arrived on May 29, 1736, with their long train of mules bearing a load of strange instruments, the streets were lined with spectators. The audiencia president, Dionesio de Alsedo y Herrera, put them up in the royal palace and greeted them with a written proclamation, grandly announcing that the two nations were uniting for the

“transcendental matters of science.” For three days, Alsedo hosted one dinner and ceremony after another for the visitors, with the

wealthy and powerful coming from miles to attend. Members of the town council, the judges of the audiencia court, church officials, and wealthy merchants all came to introduce themselves, and everyone, Ulloa and Juan wrote,

“seemed to vie with each other in their civilities towards us.”

Bouguer and La Condamine missed this grand welcome. Godin and the others, while waiting for them to arrive, joyfully explored this city of 30,000 and its environs. Quito, they believed, was the “highest situated” city in the world, its inhabitants—Bouguer would later write—

“breathing an air more rarefied by one third than other men.” All found the weather a delight, the city warmed by its proximity to the equator but cooled by its altitude, a combination that created a “perpetual spring.” The valley to the south was a sea of green and gold. Cattle grazed on grassy plots while Indians worked the plowed fields, the mild climate allowing one field to be sown while, on the same day, the one next to it was harvested. Orchards dripped with apples, pears, and peaches, and the entire valley was ringed by snow-capped volcanoes. There was Mount Cotopaxi to marvel at, as well as Antisana, Cayambe, and Illiniza, each one taller than the greatest mountain in the Alps.

“Nature,” Ulloa and Juan wrote, “has here scattered her blessing with so liberal a hand.”

Quito and its daily life were equally captivating. Stone bridges spanned the deep ravines that transected the city, adobe homes were built on steep streets, and soaring cathedrals seemed to grace every other block. Throughout the day, the peal of church bells could be heard, and inside the great chapels were

“vast quantities of wrought plate, rich hangings (tapestries) and costly ornaments,” Ulloa marveled. Markets in the city were filled with an abundance of meats—beef, veal, pork, rabbit, and fowl—and a dazzling array of colorful fruits. There were apricots, watermelons, strawberries, apples, oranges, pineapples, lemons, limes, guavas, and avocados to try, and all the members of the French expedition agreed that the most delicious New World fruit was the chirimoya, its pulp

“white and fibrous, but infinitely delicate.”

Map of Quito in 1736.

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine

, Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi à l’équateur

(1751)

.

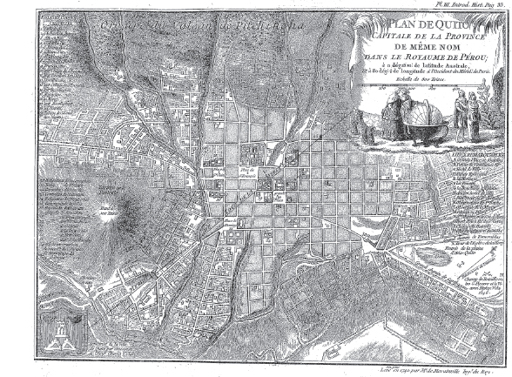

The evening festivities were formal affairs, and the two groups—guests and hosts—did their best to impress one another. The French powdered their wigs and wore their finest silk coats, while the Spanish men of Quito polished their swords, put on their black capes, and in every way possible

“affected great magnificence in their dress,” Ulloa wrote. The women of Quito were breathtaking, too, and they did not seem to mind the attention from the visitors. “Their beauty,” Ulloa confessed at the end of one particularly festive evening, “is blended with a graceful carriage and an amiable temper.”

Every part of their dress is, as it were, covered with lace, and those which they wear on days of ceremony are always of the richest stuffs, with a profusion of ornaments. Their hair is generally

made up in tresses, which they form into a kind of cross, on the nape of the neck, tying a rich ribbon, called balaca, twice round their heads, and with the ends form a kind of rose at their temples. These roses are elegantly intermixed with diamonds and flowers.

The clothing of different castes in Quito.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa

, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional

(1749), from the 1806 English translation

A Voyage to South America.

But perhaps none of the visitors were so smitten as the youngest two members of the French expedition. As Couplet whispered to Jean Godin on more than one occasion, “These women are enchanting.”

W

HEN

L

A

C

ONDAMINE ARRIVED

, he did not join his colleagues at the royal palace. Instead, he slipped quietly into town, doing his best to go unnoticed. He was very much the scruffy traveler, bemoaning the fact that he had nothing to wear. He had left the one suitcase he had been carrying in the mountains, and Louis Godin had left his other trunks in Guayaquil, which La Condamine was certain his colleague had done just to spite him.

“

Seventy

mules used to carry cargo as well as persons, and it had not been possible, in my absence, to find a place for a single one of my

trunks, nor even for my bed,” he bitterly complained in his journal. La Condamine had no clothes other than the soiled hunting outfit he had been wearing since Manta, attire that left him “incapable of appearing in public in any decent fashion.” He had a letter recommending him to the Jesuits, and he holed up with them in their compound. He remained there, out of sight, for more than a week, working on his maps while a servant fetched the goods he had left behind.

Although La Condamine felt justified in secluding himself, his behavior constituted a major diplomatic gaffe, which Alsedo took as a personal insult. A guest of La Condamine’s rank was expected to enter a city after giving advance notice so that a proper welcome could be provided. Godin and the others had understood this; they had paused a few leagues outside of Quito and sent a messenger ahead, asking the audiencia president for permission to proceed. But not only had La Condamine sneaked into town, unaccompanied by a Spaniard, he then did not even deign to introduce himself. Alsedo found this unimaginably rude, and it stirred up his underlying mistrust of these “foreigners.”

Months earlier, Alsedo had heard whispers that the French were not complying with the terms of their passports. In Cartagena, they had drawn several thousand pesos from the royal Peruvian treasury, which Philip had authorized them to do. However, while Spain had not put any limit on the amount that it would advance the expedition, the French consul in Cadiz, in a last-minute mix-up, had said it would cover these draws only up to 4,000 pesos (about 20,000 French pounds). This was a ridiculously small sum given the expedition’s expenses, and rumors had reached Alsedo that the French, while in Cartagena, had tried to sell contraband valued at 100,000 pesos. The Quito president had immediately written the viceroy of Peru in Lima for advice; the viceroy had cautioned him to carefully

“watch that the said astronomers didn’t use the royal permission for purposes that weren’t proper.” Alsedo had been on his guard even before the French had arrived, and now La Condamine had slighted him.