The Mapmaker's Wife (13 page)

Read The Mapmaker's Wife Online

Authors: Robert Whitaker

Tags: #History, #World, #Non-Fiction, #18th Century, #South America

Along the Chagres River.

From Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa

, Relación histórica del viage a la América Meridional

(1749)

.

Meanwhile, Jean Godin, Couplet, Verguin, and the other assistants, when not helping the academics with their studies, enjoyed being tourists. They sampled oysters and other regional delicacies, like iguana seasoned with red pepper and lime juice, a recipe that unfortunately failed to hide the “nauseous smell” of the reptile’s

white meat. Several times they stood along the shore and watched Negro slaves dive for pearls in the bay. Ten or twenty of them would go out in a boat at a time, and with a rope tied around their waists, they would jump overboard with small weights to accelerate their sinking. They dove to depths approaching fifty feet, Ulloa discovered, and in order to make the most of each descent, the divers would put an oyster under the left arm, one in each hand,

“and sometimes another in their mouth,” before rising to breathe. They went down time and again until their daily quota was filled, and all the while they had to be on the alert for sharks, octopuses, and huge stingrays that haunted the bay. The boat’s officer also kept an eye out for these marauders and would tug on the ropes at the first sight of one, but this scheme, Ulloa lamented, was often “ineffectual” in protecting the divers. More than one slave had lost an arm or a leg or his life to a shark, and several—or so Ulloa was told—had been killed by giant rays, a “fish,” it was said, that

“wraps its fins round a man, or any other animal, that happens to come within its reach, and immediately squeezes it to death.”

They sailed from Panama City on February 22, having chartered the

San Cristóbal

for the 800-mile voyage down the coast. They were eager to be in Peru, and yet their plans for precisely how they would proceed when they arrived were still quite unsettled. The ongoing feud between the three academicians was now focused on whether they should attempt to do their arc measurements along the coast, which Bouguer and La Condamine favored, or in the Andes, as Godin desired. The

San Cristóbal

crossed the equator on March 8, and a day later, it dropped anchor in the bay of Manta. The expedition members should have been overjoyed—the snow-capped Andes were now visible in the distance—but the tension between the three leaders was so palpable that Senièrgues, in a letter to Bernard and Antoine de Jussieu, worried that the expedition was blowing apart:

Tomorrow we are to see if the terrain will be adequate for the measurement of a base. Mr. Godin does not agree and intends to

leave for Guayaquil and from there go directly to Quito. Mr. de La Condamine already announced in front of everyone that if no one wanted to stay he would remain alone. If he feels this strongly about it, Mr. Bouguer will no doubt remain with him. Mr. Godin has not been speaking to them for some time now. They fight like cats and dogs and attack each other’s observations. It is not possible that they will remain together for the rest of this trip.

To investigate the coast, they traveled to Monte Christi, a small village about eight miles inland. They were put up by the locals in bamboo huts raised on stilts, La Condamine awaking that first night to the unsettling sight of a snake dangling overhead. After the expedition surveyed the surrounding terrain, Bouguer, on March 12, wrote a formal memorandum to Godin. If they were to do their survey work here, he argued, it would save them the time and expense of transporting their gear from Guayaquil to Quito, which would require hiring more than 100 mules. It would also be

“easier to provide for the subsistence of our company” along the coast, he wrote. Nor should it matter that King Philip was expecting them to do their work around Quito. Spain would be well served by their staying here: “I can even dare to add that it is within [the king’s] interest that our operations be carried out in the indicated place … because, in fact, we cannot conclude our work near the sea without drawing up a map which Navigators shall find invaluable.”

Although there might have been much to recommend Bouguer’s proposal, Godin did not want to discuss it. He was the leader of this expedition, Spain was expecting them to do their work around Quito, and that was that. Besides, Ulloa and Juan had explored the terrain, and they did not see the same opportunity that Bouguer did. The landscape around Manta, they wrote, was

“extremely mountainous and almost covered with prodigious trees,” which made “any geometrical operations … impractical there.”

The leaders of the group were at loggerheads, and yet at the last moment, they resolved the matter in a way that at least held open

the possibility of a later reconciliation. On March 13, everyone but La Condamine and Bouguer—and their personal servants—boarded the

San Cristóbal

, which was newly supplied with food and water. They would continue along the coast to Guayaquil and then travel inland north to Quito. La Condamine and Bouguer, having lost this particular battle, would conduct some experiments along the coast and then make their way to Quito. The bitterness of the moment, they all hoped, could be forgotten once they had some time apart, and not even Ulloa and Juan stopped to think about what else La Condamine and Bouguer might be accomplishing by staying behind. The two French academicians had barely stepped into Peru, and yet, once the

San Cristóbal

set sail, they had already freed themselves from their Spanish minders, a precedent for traveling about the colony with independence.

In anticipation of a lunar eclipse on March 26, La Condamine and Bouguer quickly built a makeshift observatory on the outskirts of Monte Christi. The event would provide them with a celestial timepiece, one much easier to use than Jupiter’s satellites, enabling them to fix the longitude

“of all this coast, the most westerly of South America.” Skies were clear that night and both were elated to have made such “an extremely important observation,” Bouguer wrote. They now knew that Monte Christi was fourteen leagues west of the meridian at Panama City, and that the nearby Cape of Saint Lorenzo was four leagues further west. When these data reached France, they enabled cartographers to draw the South American continent with much greater accuracy than ever before.

Over the next few weeks, La Condamine and Bouguer made their way north along the coast, traveling by horse along the beach. They stopped in several villages—Puerto Viejo, Charapoto, and Canow—and learned about the local folklore. Centuries ago, they were told, the people living in this region had worshipped

“an emerald the size of an ostrich egg,” which was kept in a temple. When the Spanish arrived, the natives had hidden the precious stone, and they had remained mum about it ever since. Their silence, Bouguer observed, was wise, for if the Spanish had ever

been able to find the source of the emeralds, the Indians would have immediately been put to work digging for more, a toil

“of labour painful to excess, which they alone would bear the weight, and with but little portion of the profits.”

In early April, La Condamine and Bouguer set up camp along the Rio Jama, just a few miles south of the equator. Here Bouguer spent several weeks studying the refractory properties of the atmosphere, which he had been investigating ever since reaching Petit Goave. He planned to make similar studies once he reached Quito, enabling him to answer a critical question: Was refraction—which altered the apparent position of stars—more or less pronounced at higher altitudes? This difference would have to be factored into their arc-measuring calculations. The bitter feelings of Manta had definitely subsided, and on April 23, Bouguer decided that it was time to turn back. He had finished his refraction studies, and the rigors of traveling along the coast had worn him out. He found the heat oppressive, the insects a “plague,” and he had even grown tired of the birds in the forest, which, to his ear, produced a

“discordant stunning noise.” He would hurry on to Guayaquil and try to catch Godin and the others.

La Condamine, however, was eager to continue north. While Bouguer had been at his Rio Jama camp, La Condamine had spent five days fixing the point where the equator crossed the coast. This was at

“Palmar, where I carved on the most prominent boulder an inscription for the benefit of Sailors,” he wrote in his journal. “I should have perhaps included a warning to not stop at that place; the persecution one undergoes night and day from mosquitoes and the different species of flies unknown in Europe is beyond any exaggeration.” He was happy to be on his own, with only a servant by his side, and it mattered little to him that at every step of the way, he had to fight legions of mosquitoes and drag along a bulky quadrant and telescope. These were inconveniences that any adventurer could expect.

A

FTER ARRIVING

in Guayaquil on March 26, Godin and the others were unable to depart at once for Quito, the constant rains making travel overland impossible. So much rain fell in April that the river overflowed its banks, driving “snakes, poisonous vipers and scorpions” into the houses where they were staying, Ulloa and Juan complained. The streets turned so muddy that people had to walk from the porch of one house to the next over planks set down as bridges between them. Waterlogged rats scurried about everywhere, marching through ceiling rafters at night with such a loud step that it was difficult to sleep.

On May 3, they thankfully escaped from Guayaquil aboard a chata, heading up the Guayaquil River to Caracol, a distance of about eighty miles. Indians living along this stretch of water, Ulloa and Juan noted, skillfully hunted fish with spears and harpoons. In smaller creeks, the Indians would chop up a plant root, called

barbasco

, mix it with bait, and toss the mixture into the water. The herbal concoction would knock out the fish, which would then float to the surface, enabling the Indians to scoop them up with nets. Alligators, some nearly fifteen feet long, lined the banks, and those that had tasted human flesh before were rumored to be “inflamed with an insatiable desire of repeating the same delicious repast.” But insects were the worst menace:

The tortures we received on the river from the moschitos were beyond imagination. We had provided ourselves with moschito cloths, but to very little purpose. The whole day we were in continual motion to keep them off, but at night our torments were excessive. Our gloves were indeed some defense to our hands, but our faces were entirely exposed, nor were our clothes a sufficient defense for the rest of our bodies, for their stings, penetrating through the cloth, caused a very painful and fiery itching. … At day-break, we could not without concern look upon each other. Our faces were swelled, and our hands covered with painful tumours, which sufficiently indicated the condition of the other parts of our bodies exposed to the attacks of those insects.

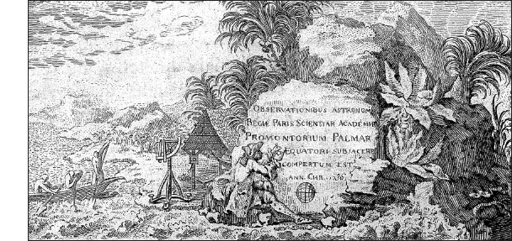

La Condamine marks the equator.

From Charles-Marie de La Condamine

, Journal du voyage fait par ordre du roi à l’équateur

(1751)

.