The Marriage Book (26 page)

Authors: Lisa Grunwald,Stephen Adler

Tags: #Family & Relationships, #Marriage & Long Term Relationships, #General, #Literary Collections

ELBERT HUBBARD

LOVE, LIFE & WORK

, 1906

For background on Hubbard, see

Friendship

.

There are six requisites in every happy marriage; the first is Faith and the remaining five are Confidence.

ERNEST GROVES

MARRIAGE

, 1933

A sociology professor at the University of North Carolina, Ernest R. Groves (1877–1946) was one of the first academics to offer a college course on marriage.

It is significant that the two words most commonly used to describe marriage success or failure are happy and unhappy. These terms are seldom employed by adults to describe other activities or other relationships. In the vocabulary of children, however, they appear frequently and are used to express judgment regarding both minor and major satisfactions and disappointments. . . . This fact suggests that the individual is likely to bring to the marriage relationship not only greater expectation and daydreaming than is carried to any other of his associations but that with this goes greater resistance to reconstruction of his expectations.

VIRGINIA WOOLF, CIRCA 1936

Despite her depressions and eventual suicide, Virginia Woolf (see

Children

) had moments of great marital joy. Even in her last note to her husband, Leonard, she wrote: “If anybody could have saved me it would have been you.” According to a friend who later repeated it to Leonard, Woolf offered the comment below in answer to a question she herself had asked: What was the happiest moment in one’s life?

I think it’s the moment when one is walking in one’s garden, perhaps picking off a few dead flowers, and suddenly one thinks: “My husband lives in that house, and he loves me.”

LEWIS TERMAN

PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS IN MARITAL HAPPINESS

, 1938

A developer of the Stanford-Binet IQ test, Lewis Terman (1877–1956) was a complex mixture of inquisitive scientist and didactic geneticist. He believed that IQ tests could not just reveal intelligence but also should influence the treatment of those who took them: better opportunities, schooling, and jobs for the “gifted,” and opposite treatment for those who scored badly—even to include the sterilization of subjects then known as “feebleminded.” Terman was also among the first psychologists to try to quantify happiness in marriage. As to the following list, he wrote: “The subject who ‘passes’ on all 10 of these items is a distinctly better-than-average marital risk. Any one of the 10 appears from the data of this study to be more important than virginity at marriage.”

The 10 background circumstances most predictive of marital happiness are: 1. Superior happiness of parents.

2. Childhood happiness.

3. Lack of conflict with mother.

4. Home discipline that was firm, not harsh.

5. Strong attachment to mother.

6. Strong attachment to father.

7. Lack of conflict with father.

8. Parental frankness about matters of sex.

9. Infrequency and mildness of childhood punishment.

10. Premarital attitude toward sex that was free from disgust or aversion.

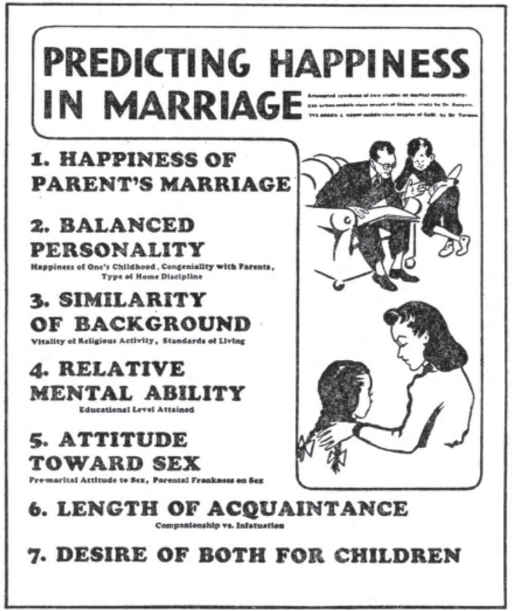

NATIONAL FORUM POSTER, CIRCA 1940

Dr. Terman’s

Psychological Factors in Marital Happiness

(see above) revealed the results of his study of 792 couples. A year later, Drs. Leonard Cottrell and Ernest Burgess published

Predicting Success or Failure in Marriage

, the result of their study of 526 couples in Illinois. A synthesis of their findings led to the creation of this poster for the National Forum, a Chicago-based private nonprofit that produced and sold educational posters and was directed by the Rev. Dr. William Russell Shull.

HOME

“THE HOUSEHOLDER OF PARIS”

THE GOOD WIFE’S GUIDE

, CIRCA 1392

This advice book’s author, popularly called “Le Ménagier de Paris,” is unknown but was purported to be a husband writing to a much younger wife. The volume included recipes for meals and home remedies, as well as tips on conversation, sexual advice, and household hints. The passages below seem like a combination of sybaritic dream and pestilential nightmare.

Love your husband’s person carefully. I entreat you to see that he has clean linen, for that is your domain, while the concerns and troubles of men are those outside affairs that they must handle, amidst coming and going, running here and there, in rain, wind, snow, and hail, sometimes drenched, sometimes dry, now sweating, now shivering, ill fed, ill lodged, ill shod, and poorly rested. Yet nothing represents a hardship for him, because the thought of his wife’s good care for him upon his return comforts him immensely. The ease, joys, and pleasures he knows she will provide for him herself, or have done for him in her presence, cheer him: removing his shoes in front of a good fire, washing his feet, offering clean shoes and socks, serving plenteous food and drink, respectfully honoring him. After this, she puts him to sleep in white sheets and his nightcap, covered with good furs, and satisfies him with other joys and amusements, intimacies, loves, and secrets about which I remain silent. The next day, she has set out fresh shirts and garments for him.

. . . I urge you to bewitch and bewitch again your future husband, and protect him from holes in the roof and smoky fires, and do not quarrel with him, but be sweet, pleasant, and peaceful with him. Make certain that in winter he has a good fire without smoke, and let him slumber, warmly wrapped, cozy between your breasts, and in this way bewitch him. . . .

If you have a room or a floor in your dwelling infested with flies, take little sprigs of fern, tie them together with threads like tassels, hang them up, and all the flies will settle on them in the evening. Then take down the tassels and throw them outside.

Item,

close up your room firmly in the evening, leaving just one small opening in the eastern wall. At dawn, all the flies will exit through this opening, and then you seal it up.

Item,

take a bowl of milk and a hare’s gall bladder, mix them together, and then set out two or three bowls of the mixture in places where the flies gather, and all that taste it will die.

Item,

otherwise, tie a linen stocking to the bottom of a pierced pot and set the pot in the place where the flies gather and smear the inside with honey,

or apples, or pears. When it is full of flies, place a platter over the opening, then shake it. . . .

In this way, serve your husband and have him waited on in your house, protecting and keeping him from all irritations and providing him all the creature comforts that you can imagine. Rely on him for external matters, for if he is considerate, he will make even greater efforts and work harder than you could wish. If you do what is said here, he will always miss you and his heart will always be with you and your soothing ways, shunning all other houses, all other women, all other services and households. If you look after him in the way this treatise urges, in comparison with you, everything else will be dust. Your behavior should follow the example of those who traverse the world on horseback. As soon as they arrive home from a journey, they provide fresh litter for their horses up to their bellies. These horses are unharnessed and bedded down, given honey, choice hay, and ground oats, and are always better tended when they return to their own stables than anywhere else. If horses are made so comfortable, it makes good sense that a person should be treated similarly upon his return, particularly a lord at his own household.

WILLIAM ALCOTT

THE YOUNG WIFE, OR DUTIES OF WOMAN IN THE MARRIAGE RELATION

, 1838

A teacher, physician, and early proponent of strict vegetarianism, William Andrus Alcott (1798–1859) was also the author of more than a hundred books and pamphlets on health, home, and diet. His extremism about diet—he eschewed all animal products and even some vegetables (“radishes,” he wrote, “are miserable things”)—was matched by a conservatism in his view of marital roles and, in particular, the need for wives to instruct, to protect, and to keep a household healthy.

Alcott, cousin of the philosopher Bronson Alcott and Bronson’s daughter, Louisa May Alcott, was referred to in a 1960s article as “The Least-Remembered Alcott,” but his influence during his lifetime was considered substantial.

The importance of chemistry to the housewife, though admitted in words, seems, after all, but little understood. How can we hope to urge her forward to the work of ventilating and properly cleansing her apartments and her furniture, until she understands not only the native constitution of our atmosphere, but the nature of the changes which this atmosphere undergoes in our fire rooms, our sleeping rooms, our beds, our cellars, and our lungs? How can we expect her to cooperate, with all her heart, in the work of simplifying and improving cookery, simplifying our

meals, and removing, step by step, from our tables, objectionable articles, or deleterious compounds, until she understands effectually the nature and results of fermentation, as well as of mastication and digestion? How can we expect her to detect noxious gases, and prevent unfavorable chemical changes, and the poisonous compounds which sometimes result, and which have again and again destroyed health and life, while she is as ignorant as thousands are, who are called housewives, of the first principles of chemical science? Would it not be to expect impossibilities?

PHOEBE CARY

“THE WIFE,” 1854

Phoebe Cary (1824–1871), the younger of the two poets known as the Cary Sisters, tended to write lighter, wittier verse than her sister, Alice. “The Wife” was her takeoff on the well-known poem “A Death-Bed,” by James Aldrich, which went: “Her suffering ended with the day, / Yet lived she at its close, / And breathed the long, long night away / In statue-like repose. / But when the sun in all his state / Illumed the eastern skies, / She passed through Glory’s morning gate / And walked in Paradise!”

Neither Cary sister was married. Born in Ohio, they lived together in New York City, where they hosted a popular literary salon.

Her washing ended with the day,

Yet lived she at its close,

And passed the long, long night away,

In darning ragged hose.

But when the sun in all his state

Illumed the eastern skies,

She passed about the kitchen grate,

And went to making pies.

CHRISTOPHER MORLEY

“WASHING THE DISHES,” 1917

American author Christopher Morley (1890–1957) was lighthearted and prolific in verse, fiction, and essays. He was also a judge for the Book-of-the-Month Club and an editor of several editions of

Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations

. Ironically, one of his own best quotes never made it into that collection: “Read, every day, something no one else is reading. Think, every day, something no one else is thinking. Do, every day, something no one else would be silly enough to do.”

Morley had been married—to Helen Booth Fairchild—for three years when he wrote this poem. They would have four children together. “Willow cup” refers to the popular eighteenth-century Blue Willow china pattern.

When we on simple rations sup

How easy is the washing up!

But heavy feeding complicates

The task by soiling many plates.

And though I grant that I have prayed

That we might find a serving-maid,

I’d scullion all my days, I think,

To see Her smile across the sink!

I wash, She wipes. In water hot

I souse each dish and pan and pot;

While Taffy mutters, purrs, and begs,

And rubs himself against my legs.

The man who never in his life

Has washed the dishes with his wife

Or polished up the silver plate—

He still is largely celibate.