The Marriage Book (28 page)

Authors: Lisa Grunwald,Stephen Adler

Tags: #Family & Relationships, #Marriage & Long Term Relationships, #General, #Literary Collections

EDWARD HARDY

HOW TO BE HAPPY THOUGH MARRIED: BEING A HANDBOOK TO MARRIAGE BY A GRADUATE IN THE UNIVERSITY OF MATRIMONY

, 1886

The “though” in the title may seem ironic, but there wasn’t much humor to be found in this volume by the Rev. Edward John Hardy (1849–1920). A British chaplain who served with his country’s armed forces in various foreign outposts, he approached his subject with stereotypical Victorian cultural and religious convictions, stressing compromise and mutual respect. But he showed particular attention to the way marriages started, writing: “In matrimony, as in so many other things, a good beginning is half the battle.” By that reasoning, it followed that the best beginning would be the best honeymoon.

[The honeymoon] certainly ought to be the happiest month in our lives; but it may, like every other good thing, be spoiled by mismanagement. When this is the case, we take our honeymoon like other pleasures—sadly. Instead of happy reminscences, nothing is left of it except its jars.

You take, says the philosophical observer, a man and a woman, who in nine cases out of ten know very little about each other (though they generally fancy they do), you cut off the woman from all her female friends, you deprive the man of his ordinary business and ordinary pleasures, and you condemn this unhappy pair to spend a month of enforced seclusion in each other’s society. If they marry in the summer and start on a tour, the man is oppressed with a plethora of sight-seeing, while the lady, as often as not, becomes seriously ill from fatigue and excitement.

A newly-married man took his bride on a tour to Switzerland for the honeymoon, and when there induced her to attempt with him the ascent of one of the high peaks. The lady, who at home had never ascended a hill higher than a church, was much alarmed, and had to be carried by the guides with her eyes blindfolded, so as not to witness the horrors of the passage. The bridegroom walked close to her, expostulating respecting her fear. He spoke in honeymoon whispers; but the rarefaction of the air was such that every word was audible. “You told me, Leonora, that you always felt happy—no matter where you were—so long as you were in my company. Then why are you not happy now?” “Yes, Charles, I did,” replied she, sobbing hysterically; “but I never meant above the snow line.” It is at such times as these that awkward angles of temper make themselves manifest, which, under a more sensible system, might have been concealed for years, perhaps for ever.

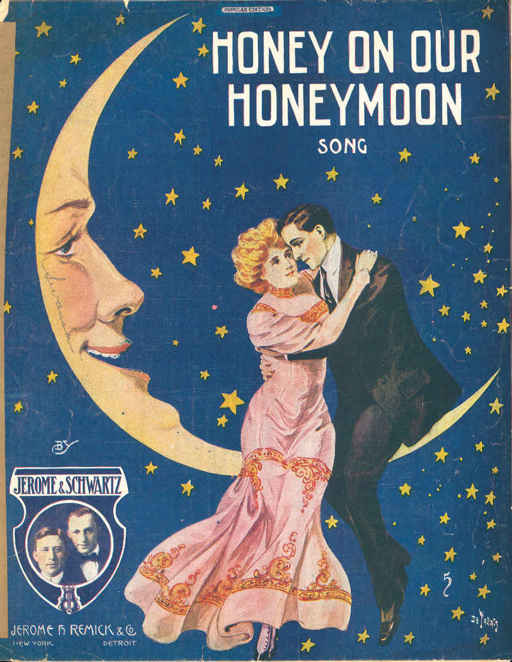

SHEET MUSIC COVER, 1909

H. W. LONG

SANE SEX LIFE AND SANE SEX LIVING

, 1919

An early advocate of eugenics who wrote that “if the breeding of human beings were as carefully managed as that of horses and cattle, the results would be no less remarkable,” Harland William Long (1869–1943) was a practicing physician and notably even more candid in his advice about sex than William J. Robinson (see

Grievances

;

Sex

).

Long’s book was one of many volumes targeted by Boston’s Watch and Ward Society, a particularly rabid antivice organization that, spanning the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, censored the books, plays, and pastimes it deemed objectionable; the group was responsible for the accuracy and the allure of the phrase “Banned in Boston.”

Both [bride and bridegroom] must be

taught

to

“Know what they are about”

before they engage in the sexual act, and be able to meet each other sanely,

righteously, lovingly,

because they both

desire

what each has to give to the other; in a way in which neither claims any

rights,

or makes any

demands

of the other—in a word, in

perfect concord

of agreement and action, of which mutual love is the inspirer, and

definite knowledge

the directive agent.

Such a first meeting of bride and bridegroom will be no raping affair. There will be no shock in it, no dread, no shame or thought of shame; but as perfectly as two drops of water flow together and become one, the bodies and souls of the parties to the act will mingle in a unity the most perfect and blissful that can ever be experienced by human beings in this world. This is no dream! It is a most blessed reality, which all normally made husbands and wives can attain to, if only they are properly

taught and educated

, if only they will learn how to reach such blissful condition.

MARGARET SANGER

HAPPINESS IN MARRIAGE

, 1926

Like Long (above), Margaret Sanger (1879–1966) had some choice words for the way sex could go right or wrong on the honeymoon night. The mother of the birth-control movement, arrested eight times for distributing information about contraception, Sanger was downright pragmatic when it came to what she called the “alone at last” moment.

The custom of the wedding journey offers both advantages and disadvantages. Too often decisions concerning the bridal night are determined by train schedules and such exigencies. It should be obvious to all sensible people that a Pullman car is hardly suitable for the consummation of romance or a proper setting for the first conjugal embrace.

ISABEL HUTTON

THE SEX TECHNIQUE IN MARRIAGE

, 1932

The chapter on “Preparation for Marriage” advised engaged couples to consider money, race, nationality, “feeblemindedness,” and the possible effects of illnesses from syphilis to insanity as reasons to question or cancel their plans. But for couples who managed to run the gauntlet, Scottish physician Isabel Emslie Hutton (1887–1960) offered less radical advice on honeymoon sleeping arrangements.

The place where the honeymoon is to be spent should be well considered, for the impression it makes is very important and means a good deal to a sensitive woman. If possible it should be beautiful and quiet, but not so isolated that the young couple will be thrown entirely on their own resources. There must be something in the way of walking, games, or other entertainment. It is a great mistake to do a long tour or to travel about, and far more sensible to arrange to stay quietly in one place for most of the time. The accommodation should be as good as the man can afford, and carefully chosen; if possible there should be a dressing-room for the man, and at first perhaps the best arrangement is to have two beds. Probably this is the most healthy and practical plan to follow throughout, but whatever husband and wife decide to do later on, will depend on their individual temperaments.

Having separate beds in the early days makes it much easier both for the woman, who is thus introduced more gradually to the conditions of married life, and for the man because he has not the intimate physical contact which is so sexually exciting for him, especially at this time.

These things may seem too small to mention, but to a sensitive woman they may make just all the difference between the beginnings of a happy married life and an unhappy one.

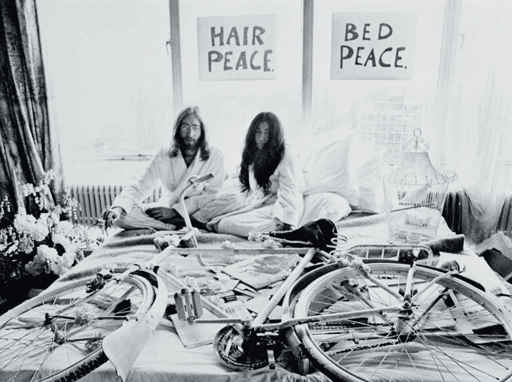

JOHN LENNON AND YOKO ONO, 1969

For fans of the Beatles, Yoko Ono was an enigma from the start. With her conceptual art, sitar-like voice, and overall etherealness, she was a constant source of press coverage and speculation. When she married John Lennon (1940–1980) in 1969, the couple invited reporters and photographers to their “Bed-In,” where their honeymoon suite was decked out with signs for peace. The event was immortalized in a bevy of iconic photographs, and in John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s subsequent “Ballad of John and Yoko,” featuring the lines, “The newspeople said, ‘Say, what’re you doing in bed?’ / I said, ‘We’re only trying to get some peace.’ ”

IAN M

C

EWAN

ON CHESIL BEACH

, 2007

Set at an English Channel resort in 1962, the thirteenth book of fiction by Ian McEwan (1948–) tells the story of two virgins, Edward and Florence, on their honeymoon. Their love is not in question, but it turns out that they have vastly different desires: he to experience, at last, the wonders of sex; she to avoid it at all costs. Their two needs collide, finally—and, for their marriage, fatally—in this passage.

Prompted by her laughter, he moved closer to her again and tried to take her hand, and again she moved away. It was crucial to be able to think straight. She started her speech as she had rehearsed it in her thoughts, with the all-important declaration.

“You know I love you. Very, very much. And I know you love me. I’ve never doubted it. I love being with you, and I want to spend my life with you, and you say you feel the same way. It should all be quite simple. But it isn’t—we’re in a mess, like you said. Even with all this love. I also know that it’s completely my fault, and we both know why. It must be pretty obvious to you by now that . . .”

She faltered; he went to speak, but she raised her hand.

“That I’m pretty hopeless, absolutely hopeless at sex. Not only am I no good at it, I don’t seem to need it like other people, like you do. It just isn’t something that’s part of me. I don’t like it, I don’t like the thought of it. I have no idea why that is, but I think it isn’t going to change.” . . .

“I’ve thought about this carefully, and it’s not as stupid as it sounds. I mean, on first hearing. We love each other—that’s a given. Neither of us doubts it. We already know how happy we make each other. We’re free now to make our own choices, our own lives. Really, no one can tell us how to live. Free agents! And people live in all kinds of ways now, they can live by their own rules and standards without having to ask anyone else for permission. Mummy knows two homosexuals, they live in a flat together, like man and wife. Two men. In Oxford, in Beaumont Street. They’re very quiet about it. They both teach at Christ Church. No one bothers them. And we can make our own rules too. It’s because I know you love me that I can actually say this. What I mean, it’s this—Edward, I love you, and we don’t have to be like everyone, I mean, no one, no one at all . . . no one would know what we did or didn’t do. We could be together, live together, and if you wanted, really wanted, that’s to say, whenever it happened, and of course it would happen, I would understand, more than that, I’d want it, I would because I want you to be happy and free. I’d never be jealous, as long as I knew that you loved me.” . . .

He made a noise between his teeth, more of a hiss than a sigh, and when he spoke he made a yelping sound. His indignation was so violent it sounded like triumph. “My God! Florence. Have I got this right? You want me to go with other women! Is that it?”

She said quietly, “Not if you didn’t want to.”

“You’re telling me I could do it with anyone I like but you.”

She did not answer.

“Have you actually forgotten that we were married today? We’re not two old queers living in secret on Beaumont Street. We’re man and wife!”

The lower clouds parted again, and though there was no direct moonlight, a feeble glow, diffused through higher strata, moved along the beach to include the couple standing by the great fallen tree. In his fury, he bent down to pick up a large smooth stone, which he smacked into his right palm and back into his left.

He was close to shouting now. “With my body I thee worship! That’s what you promised today. In front of everybody. Don’t you realize how disgusting and ridiculous your idea is? And what an insult it is. An insult to me! I mean, I mean”—he struggled for the words—“how you!”

HUSBANDS, HOW TO GET

JOHN ADAMS

DIARY, 1761

American independence was still fifteen years away when the future U.S. president John Adams (1735–1826) wrote this draft of a letter that scholars believe was intended to be published as an essay. The nieces were a literary device, and though the tone of the letter is mature and instructive, Adams himself had yet to marry the famous Abigail.