The Nature of Ice (20 page)

Packed on Ninnis's sledge were two of the dilly bags Paquita and her mother had stitched by hand. Before leaving Hobart he had opened her parting gift to find one dozen calico bags in the boldest shades imaginableâ

vibrant

colours

, she had written,

to remind you and your little hutful

of men of the goodness and warmth of home

.

A quarter-mile ahead, breaking trail for the little pilgrimage, Mertz glided on skis. He belted out one of his student songs with such patriotic fervour that any moment now Ninnis would launch into a yodel to set the dogs howling too.

Mertz had made it his mission to bear out the worthiness of skis in Antarctica. Every so often he made a show of halting and gazing back, hand on hipâan exaggerated yawn, do you mindâwhile Douglas, Ninnis and the dog teams clambered in his wake through patches of knee-deep snow.

Ninnis had woken this morning his old jolly self, prattling

this time last year

. . . ,

this time next

year

. . ., rough-housing with Mertz and playing the giddy goat as they harnessed the dogs. Cherub had done himself a disservice by remaining stoic for so long; when Douglas finally lanced his whitlows, his fingertips were purple and bulbous with pus.

Douglas reached a stretch of névéâold, compacted snow indicative of a snow bridgeâand stepped onto the sledge to spread his weight. Back on fresh snow, he flicked the whip and shouted, âLook out behind you, X. I'm hot on your tail!'

Thirty feet behind Douglas, Ninnis called to his team of dogs. Douglas turned to see him jump off the back of his sledge and run alongside the dogs to give old Franklin a hasten-along.

They were a jolly team trundling east in only a whisper of breeze, a balmy fifteen degrees Fahrenheit, the dogs pulling eagerly with their brushes flicked towards the sky.

Until yesterday a third sledge had carried the heaviest load to save the runners of the other two. Discarding it represented more than their imminent approach of the halfway mark. Men and dogs had slogged unyieldingly, traversing two crevassed rivers of ice so large that Douglas pictured their tongues slicking out across the ocean for fifty miles. Yesterday's ritual of redistributing the load equally between his sledge and Ninnis's was affirmation that they were fairly humming along; for once the expedition was all harmony and order.

Forgotten was the calamity of Tuesday's broken bottle of primus spirit, though for two pins Douglas could have throttled Mertz for his wild, clumsy ways. Fading too was the tedious zigzagging at the glacier's headwaters to detour around filled-in crevasses one hundred feet across. They had skirted pie crusts of ice whose frozen depths boomed as ominously as cannon fire. He'd lost count of the detours to avoid yawning mouths of ice with jaws hinged open.

The dogs slowed to a languid pace and today he didn't mind. Sledging was rarely the relaxing pastime some imaginedâmost hours were spent heaving the load across waves of sastrugi, or untangling brawling beasts, or loping alongside to keep their bearing true. Tracts of glorious smooth terrain that allowed one to actually ride the sledge and relax for a timeâwell, moments like these were pure gold.

âI still have my eye on you, George,' he growled. George might be solid ivory between the ears but he was cunning enough to put just enough weight on the trace to feign the effort of pulling. Ninnis's rear team comprised the pick of the dogs, while his front teamâat greater risk of encountering a crevasseâboasted a motley collection of loafers, wasters and mischief-makers. If Haldaneânamed by Ninnis after the bigwig in Whitehall who had objected to his secondment from the armyâranked as the ugliest dog, then Johnson wore the medal for foulest odour. Mary and Pavlova worked only for as long as their ladyships were of the predilection, while Ginger, having recently dropped a litter of pups, pulled her little heart out but simply lacked the power of the larger dogs.

Douglas took the almanac from his kitbag to calculate the noon observations. He saw X raise his ski stock in caution then glide on. When his dogs reached the same place Douglas saw no sign of hazard and eased back on the sledge. The dogs trotted over a patch of névé marked with a hint of a depression, similar to many they'd crossed before. Still, Douglas turned back and called a warning to Ninnis who paced alongside his team. Ninnis's reactionâswinging the dogs to face the névé straight onâwas practice honed to instinct. The Far Eastern Sledging Party was a cracking

A-One

team.

Douglas returned to his sums, savouring air gentle with the slick of wooden runners over ice, crunches of snow beneath dogs' paws, a faint whimper from one of the team at the rear who was likely feeling the lick of Ninnis's whip.

âHear that, Georgey boy?' Douglas called. âYou'll be in for some of that if you don't pull your socks up.'

Latitude 68°, 53', 53" south

;

longitude 151°, 39', 46"

: three hundred miles east of winter quarters. The hour was nigh to depot the bulk of food and gear from Ninnis's sledge, make one final dash and stake the Union Jack at the furthest east.

In the name of King George the Fifth

.

Douglas glanced up and saw Mertz had halted, his head canted in puzzlement as he peered back along their tracks.

Douglas turned, stung to see nothing behind him but a single set of tracks. He rolled off the still-moving sledge and raced back, thinking a rise in the terrain had hampered his view of Ninnis and his team. Even then, part of him knew. Too late, he knew.

A CHILL BELCH FROM THE crevasse.

The contorted mouth of the smashed ice lid exposing an abyss too wide to bridge. His frantic wave to Mertz to bring the sledge and rope. The echo of their calls bouncing shrill and alien off walls as sheer as glass and a piercing iris blue. The stygian gloom below.

A pathetic cry and struggle of a dying dog, its back broken, caught on a ledge so impossibly far down the animal looked as small as a mite. The futile farce of spooling out one hundred and fifty feet of fishing line to estimate the distance to the shelf below. They might as well splice all their lengths of alpine rope and try climbing to the moon.

Only with field glasses could he make out broken pieces of the sledge littered over the shelf: the remains of the tent, and a canvas food tankâthe fortnight's rations representing a fraction of man and dog food swallowed by the crevasse.

No sign of human life.

The hoarseness of their voices ragged from three hours of calling; another onset of neuralgia that skewed Douglas's face into a grimace and seized him by the throat when Mertz began to weepâwhat should he do? What could he do but take action, however inane, and walk X away,

Come,

Xavier

; support his arm and steer him to the rise; go through the mechanics of recording a bearing with trembling fingers and the tic of an eye.

One last pitiful hour sounding with a weight and bawling into the crevasse,

Ninnis! Ninnis! Cherub!

, as if refusal to relinquish hope might resurrect an angel.

Fallen comrade . . . Supreme sacrifice.

Words of his own to ease Mertz away, for no bible's prayer would save the two of them.

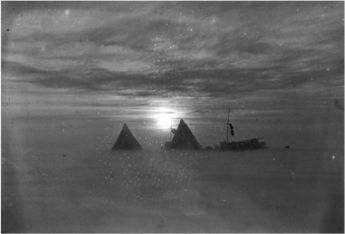

Frank Hurley's Southern

Sledging Party and the

Southern Support Party

camped on the plateau,

December 1912

>> Merry Christmas, sweetheart. The wee hours here in Perth, the night too hot and sultry to contemplate bed. The temperature still hasn't dropped below 30. Ghastly. I'm trying to conjure images of ice and picturing you sound asleep . . .

Two am at Davis Station, in front of her computer and too wired for sleep, Freya's mind is aswirl with replays and imaginings. Flakes of snow catch on her studio window only to be whisked away by the next flurry of wind. She watches the last of her images download. Those she took tonight could as easily belong to Hurley's timeâthe evening sunlight diffused by falling snow, the distant glow of Davis Station, and everything around them sepia soft.

She opens the photo that Marcus attached to his email: two tents staked upon the plateau. In nine weeks of sledging south across the ice cap, how did Frank Hurley, restricted to a single camera and a handful of glass plates, determine which of the prime times to preserve on film? She pictures him standing at a distance, absorbing the meagre camp amid the endless expanse. He captured this moment for the same pictorial qualities she sees in her own evening's images of the sea iceâlow atmospheric light, everything soft-edged with low scudding drift, sky aglow.

How did you become so enthralled by Hurley?

Chad had said tonight as they returned across the ice to their bikes.

I love his passion for photography, that he saw it as art, that

he strived to be good and taught himself all he knew. I think he

was adventurous and good-humoured, and he loved nature.

Chad nudged her.

So many of my own fine qualities.

That struck her as true, though she hadn't said.

On Hurley's man-hauling trek from winter quarters to the south magnetic pole, he kept a sledging journal. Calm conditions one day, the next,

frigid wind that parched and stung our faces

; the extract in Marcus's email brims with undiluted joy:

>> In spite of these conditions there is something grand and inspiring in treading these virgin snows and breaking trail for the first time across the unknown.

Her own days are a joy, the place a meditation, riding across tracts of ice with the tireless help of a quietly self-assured man. In a different setting she might have overlooked such absence of pretence. In different circumstances, if she were freeâFreya halts her thoughts.

You think you would have liked Hurley, as a person?

I know I would

, she'd said to Chad tonight.

He was a bit of

a showman, but that's okay. Marcus says he lived his whole life

as an idealistic adventure, playing out his boyhood hero quest.

There's a touch of the adventure hero in all of us, I'd like to

think.

Chad propped against her bike while she tied on her camera gear.

I wish you could see winter quarters. To some it's

just an old wooden shell slowly filling up with ice and disintegrating

by the year, but it stands for so much more. The final piece of the

planet to be explored.

The last great region of geographical mystery

âso Marcus had written, revising her proposal to the Arts Councilâ

the

first to be explored in conjunction with the camera

. Freya scrolls down the screen.

>> Call me this morning when you read this; I'll be heading over to your mother's around ten. I have your gifts ready to take.

Chad had glanced at his watch,

Midnight

.

It's Christmas

Day

.

Freya placed her arm around his shoulder. She kissed him lightly.

Happy Christmas. I'm so glad you're here.

He drew her towards him, held her gently, flakes of snow falling through the silence that closed around them and ushered in the day.

FREYA WAKES A FEW HOURS later, showers and dresses. She makes her way toward the living quarters, shunted along the road by an assault of wind that squeals and swirls through Davis Station. Gusts eddy around foundations of buildings, gathering up a mix of grit and snow that sprays against her hood and jacket.

A hardy few linger outside the main building: Freya sees their bodies turned from the onslaught of snow, clinging to railings, shielding their eyes as they wait for Santa and the traditional Christmas parade.

Hurrying indoors, she finds a seat at the window beside Kittie. Both of them watch the road for Santa through the blindness of white. From a corner of the room the choristers belt out a repertoire they've been practising for weeks. Big Davo, the strongest tenor, has been positioned at the back, but he still overpowers the singers in the front. Giant baubles hang from ceiling beams, bookcases are draped with fairy lights, and gifts form a rickety, unkempt pile around a disfigured plastic tree.

Through the window, four quad bikes emerge into view with an old sleigh in tow. Santa sits atop the wooden relic encircled by a huddle of shivering elves. Freya chortles when his elasticised beard blows up over his goggles and is scooped from his face by the wind. âIt's Malcolm!'

Cheers and applause herald Santa's entry to the room, his windblown elves prancing after him. Last to enter is a herd of blokey reindeers sauntering incognito behind reflector sunglasses and plastic noses, all the more photogenic, Freya takes up her camera, in their Hazmat suits and weather-beaten antlers.

Sixty people squeeze into a room designed for forty. Bodies spill into the foyer, congregate on stairs and line the walkway while the kitchen, with its promise of a banquet, remains strictly out of bounds.

Across the room, Chad returns her smile. He leans against a wall, his hair tied back, clean-shaven, wearing good trousers and a chambray shirt, a thorough contrast to his appearance last night.