The New Policeman (24 page)

Authors: Kate Thompson

When J.J. appeared in the kitchen doorway, her reaction was delayed. For an instant his presence there seemed like the most natural thing in the world, as though he had just walked up from the school bus. When the truth hit her, Helen went so weak at the knees that she had to hold on to the table for support as she stood up.

But J.J.’s behavior wasn’t appropriate to the situation either. There was nothing in his manner to

suggest that he had just returned from a month’s unexplained absence. He plonked himself down in his usual chair and examined the flute that he was holding in his left hand.

“Where have you been?” Helen relinquished her grip on the table and hurried over to him.

J.J. flashed her a rapid, wild-eyed glance, then returned his attention to the flute.

“Nowhere,” he said. “I dropped the cheese in to Anne Korff and then—” He broke off. There was a place in his mind where something was missing. He knew about the flute he was holding, but he couldn’t remember where it had come from. “It used to have a ring across the middle where one end of it was older than the other,” he said. “I can’t see it now.”

“J.J….” Helen didn’t know what to say. He looked exactly as he had when she last saw him, but he wasn’t the same. He must know how worried they had been. Surely he would tell her?

“It was your grandfather’s,” said J.J. “His name is on it. Look. John Joseph Liddy.”

“Where did you find it?”

“It must have been in the souterrain,” said J.J.

“In the souterrain? What were you doing in there?”

The only response J.J. made was to open his right

hand, which, until then, had been clutched tight around something unseen. It was full of black dust, which trickled out between his fingers onto the worn flagstones.

“It’s Bran,” he said.

Helen’s heart sank. Whatever had happened to J.J. had twisted his mind.

“It’s not bran, love,” she said gently.

“Not that kind of bran,” said J.J. “It’s a dog.”

But even as he said the words, they made no sense to him. There were things bobbing around in that vacant place; words and images that didn’t add up to anything. They frightened him. He wiped his hand on his jeans and scrubbed at the dust on the floor with his toe.

Helen was treading carefully, unsure how to deal with J.J.’s obvious disturbance. She resorted to the usual comfort.

“Come on. Take off your jacket there, and I’ll make a fresh pot of tea.”

He allowed her to help him take it off, moving the flute carefully from one hand to the other. As Helen hung the jacket up behind the door, she noticed that it was unusually bulky. All the outside pockets were bulging with something soft. Surreptitiously she

slipped her hand into one of them. What she found there did nothing to reassure her fears about her son’s state of mind. The pocket, and all the others as well, was stuffed to bursting with odd socks.

Helen turned, unsure whether to ask J.J. about them. He was just raising the flute to his lips and, after a few practice blows, he began to play a tune. Helen stood and listened. She didn’t know the tune, but the exquisite tone of the old instrument seemed familiar to her, as though the memory of it had been passed down to her through her mother’s blood.

“It’s beautiful, J.J.,” she said when he had finished.

“What’s the name of it?” he asked.

“I’ve no idea. I never heard it before. Where did you learn it?”

“I don’t know,” said J.J. But he could hear it in his head, played by fiddles and flutes and a bodhrán, and he could see people dancing. “Are we having a céilí tonight?”

“No,” said Helen. “I called it off.”

“Why?”

“Because you weren’t here.”

“But I am here. Call it back on again.”

“Is that what you want?” said Helen.

“Why wouldn’t I?” said J.J.

Helen thought about it. Why not? A céilí could be just what J.J. needed. Hadn’t the great Joe Cooley himself once said, “’Tis the only music that brings people to their senses”? Her heart warmed to the idea, and her concern for J.J. diminished. He was back, that was what mattered. In time he would feel able to explain where he had been, but in the meantime, Father Doherty or no Father Doherty, the Liddys would celebrate J.J.’s return.

But there were other things to be taken care of.

“We will have a céilí,” said Helen. “But first we have to let the police know that you’re back.”

“The police?” said J.J. “Why on earth would you want to tell the police?”

It was only then that J.J. discovered the truth about how long he had been away.

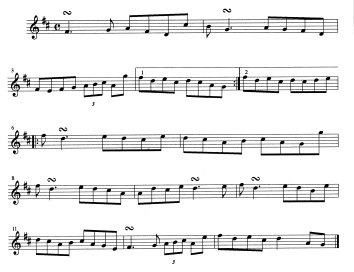

WELCOME HOME

Trad

The new policeman had just reported for duty when Sergeant Early received the phone call from Helen Liddy. It was the second piece of good news to have arrived that day. A few hours earlier Séadna Tobín, the chemist, had turned up in the village. He was most apologetic for having wasted the Gardai’s time and assured everyone that it wouldn’t happen again. Under pressure, he confessed that he had been off on the tear with his fiddle. It was a weakness of his, he said. He intended, for the time being at least, to padlock the fiddle in a trunk and give his wife sole custody of the key.

“Both keys,” he added, as an afterthought.

Now they’d found the Liddy boy as well, that just left Anne Korff and Thomas O’Neill. With a bit of luck they would soon turn up as well.

Saturday was a busy night for the police in Gort. Sergeant Early would have liked to go himself to visit the Liddys, but he was needed in the station. He would rather have sent anyone other than O’Dwyer, but he was, he had to admit, faced with no alternative. The other members of the force were already away on calls, and Garda Treacy, who ought to have been there, had failed to turn up.

“His car is there,” said Larry. “His dog is in it, but he isn’t.”

“I didn’t know he had a dog,” said the sergeant. “You’ll have to visit the Liddys on your own, so. But tread carefully, you hear? There’s no knowing what that boy might have been through.”

Marian and Ciaran arrived soon after Helen had spoken to Sergeant Early. They were as surprised and delighted, and soon as concerned, as Helen was. J.J. had been badly shocked to learn that he had been away for a month, but as time went on and some kind of semblance of family normality began to return, he relaxed and appeared to be recovering well. Marian, in her usual perceptive way, honed in on the best method of keeping him focused on the present. She told him all the latest gossip from the village, filling him in on

the disappearances first, then going on to the more humdrum stuff like the hurling results, the breakups and makeups, the appearance of white donkeys, and associated trivia. Neither she nor the others mentioned the discovery of the body in the souterrain. There would be time enough for that in the future.

When Helen brought the policeman into the kitchen, J.J. recognized him. A name was on the point of escaping from his lips when some strong instinct urged him to keep them closed. Before he could get a grip on them, the name and the face had both slithered away again, back into the place where the whole of his lost month was hiding.

Marian was out in the hall, phoning every musician and dancer in the county. The policeman sat opposite J.J. at the table, and Helen and Ciaran, after hovering uncertainly for a minute or two, settled into the armchairs on either side of the range.

But the interview was remarkably brief. J.J. told the policeman that he could remember nothing. Three or four questions later, there had been no progress beyond that basic but comprehensive stumbling block. J.J. didn’t mention the flute and, on reflection, Helen decided that she wouldn’t either. If the forensics people had overlooked it during their examination of the

souterrain, that was their problem. She had no desire to further incriminate her grandfather.

Garda O’Dwyer felt that there was probably a way of dealing with situations like this, but if he’d ever learned about them, he’d already forgotten. He suggested that a visit to their GP would do J.J. no harm, and if that turned up no causes for the amnesia they might consider arranging an appointment with a counselor. Helen and Ciaran agreed readily.

“Right, so,” said the new policeman. “It’s good to see the lad back home again, anyway. If there’s anything else we can do, let us know.”

“Will you have a cup of tea before you go?” said Helen.

“I won’t, thanks all the same.”

“We heard on the grapevine that you’re a great fiddle player.”

“Ah, well. I wouldn’t say great.”

Helen stood up and took J.J.’s fiddle down from the wall. “Did you ever see a fiddle like this one?”

J.J. was embarrassed. Helen always did this: showed off his fiddle to anyone who might know anything about them at all. They always agreed that it was a wonderful instrument, but then what else could they say?

The policeman took the fiddle and gazed at it.

Gradually, a fond smile appeared on his face. J.J. watched him. Memories were darting around just beneath the surface of his consciousness, but they were quick and slippery, like little fish, and he couldn’t quite get a grip on them.

“I did, once,” said Garda O’Dwyer, handing the fiddle back to Helen. She took it back, disappointed that he showed no inclination to play it.

“We have a céilí here tonight,” she said.

“A céilí,” said O’Dwyer. “Very good.”

“You’d be more than welcome to come.”

“That’s very kind of you, but I’m on duty. And when I’m finished for the night, I shall more than likely go home.”

“Well,” said Helen, a little crestfallen, “there’ll be another one next month.”

“I doubt if I’ll be here then.” O’Dwyer stood up and moved toward the door. “Good-bye, J.J.,” he said. “Perhaps we’ll meet again. Some other time.”

J.J. said nothing as the policeman left. The memories were jumping now, like the same little fish rising after flies. But he still couldn’t see them clearly.

“Strange character,” said Helen.

“Certainly is,” said Ciaran. “Did you see his face when you showed him the fiddle?”

“I wouldn’t mind that so much,” said Helen. “But how could you take a policeman seriously when he’s wearing odd socks?”

J.J. stared at the door. That was it. That was the net that brought the memories, twisting and shimmering, up to where he could see them. And here, in a world with a time scale, they fitted themselves, quickly and neatly, into a pattern that he hadn’t seen before.

He ran to the door and out into the yard. The policeman was walking briskly down the drive, barely visible in the approaching night. J.J. ran to the gate and called out after him. The policeman stopped and waited. When J.J. caught up with him, he said, “What did you just call me?”

“Granddad,” said J.J.

“Oh,” said the policeman. “That’s all right then. It sounded a lot like ‘Aengus’ to me.”

“Would I call you that?” said J.J., falling happily into step beside his fairy grandfather.

“No,” said Aengus. “You’d know better. Unlike some people.”

They walked on a bit farther, delighted to be in each other’s company again so soon.

“Where did you leave your car?” said J.J.

“In a ditch,” said Aengus. “I still can’t understand

why you people think two cars can pass each other on these roads.”

“They can,” said J.J. “It’s ploddy magic. Where are you going now?”

“Home,” said Aengus. “I’ve had enough of indulging my fantasies for at least another century or two. Besides, the job’s done, isn’t it? The leak is mended.”

“And did it help?” said J.J. “Being a policeman?”

“Not remotely,” said Aengus. “I can’t imagine why I ever thought it would.”

They walked on in agreeable silence for a bit farther, then Aengus went on, “Will you come for a visit?”

“I’ll be there in no time,” said J.J. “But I’d better wait awhile until things settle down here.”

“As long as you don’t forget,” said Aengus.

“I won’t,” said J.J. “But you will. A couple of dances and you’ll have forgotten I ever existed.”

“Maybe three,” said Aengus.

“Should I tell Mum, do you think?” said J.J.

“Best not to. She wouldn’t believe you, and if she did it would be worse. You people seem to have difficulty with the notion of having parents who are younger than you.”

“I suppose so,” said J.J.

Helen was calling him from the gate.

“I’d better go back. Will you do one thing before you go home?”

“What thing?”

“Turn that white donkey back into Thomas O’Neill?”

“No bother,” said Aengus Óg.

He walked away down the road, and it appeared to J.J. that he vanished from his sight just a fraction before the darkness swallowed him up. J.J. was to meet up with him again, of course, and all the others in Tír na n’Óg as well. But neither the new policeman nor Anne Korff were ever seen in Kinvara again.

GRANDFATHER’S PET

Trad