The New Policeman (23 page)

Authors: Kate Thompson

“You did not,” said Aengus. “That man knew more about this world than I do. He knew what he was doing.”

“But he can’t have. He couldn’t have gone through the wall knowing that he would be dead by the time he got to the other side.”

“Why not?” said Aengus. “He hated Tír na n’Óg and its people. He wouldn’t have wanted to stay here. He was a man of the cloth, J.J. I’m sure he expected to walk straight into another kind of eternity and find great favor with his Father up there. And who knows? Maybe he has.”

J.J. looked across the plains to the sea. The whole vista glowed in the soft light. Unless someone else like Father Doherty came along, this was the way Tír na n’Óg would stay, basking forever in this warm, golden evening.

“I’d better go home.”

“You’re free to do as you like,” said Aengus, “but I’d advise against it.”

“Why?”

“What makes you think you’re any different from Oisín and Bran and Father Doherty?”

“But that’s ridiculous,” said J.J. “I’ve only been here—” He stopped. That was the whole point. No time passed here. A thousand years could go by in Ireland, but here it was always now. The dreadful truth dawned upon J.J.

“Look on the bright side,” said Aengus Óg. “You can stroll around in the sunshine. You can learn some new tunes, and I hear you’re a great dancer as well.”

“But what about my parents?” said J.J.

“Don’t worry about them. They’ll miss you for a dance or two, and then they’ll forget all about you.”

“No, they won’t. We’re not like you, Aengus. We don’t live in the eternal present. We don’t forget.”

“Oh,” said Aengus. “Well. Too bad. Chances are they’re long gone by now anyway. Ploddies don’t last, you know.”

“Don’t say that!” said J.J. “It can’t be true.”

Aengus reached out and tousled J.J.’s hair affectionately. “Come on,” he said. “Don’t let it get you down. There’s nothing you can do, so you may as well forget about it. You belong here. You’re one of us.” An idea struck him. “Can you play that yoke?”

J.J. looked at the flute. He had forgotten it was there. One end of it was blackened and dusty from seventy years of exposure to the souterrain in his own world. The other was as clean and shiny as when his great-grandfather had last played it. He didn’t want to forget his parents and his predicament, but the truth is that few can resist the subtle powers that the land of eternal youth has over the people who find their way to it.

Perhaps Aengus was right? Perhaps there was nothing that J.J. could do? He pulled up a handful of

grass and rubbed the grime and cobwebs off the flute. The wood had been so well tempered by its years as the spoke of a cartwheel that it had not suffered at all from its time in the wall. J.J. lifted it to his mouth and blew into it. There was nothing in it but whistles and wheezes.

Aengus had the fiddle out. “Try again,” he said.

More wheezes and squeaks. And then, or now, a clear, mellow note. J.J.’s fingers moved instinctively, picking out a few short phrases and arpeggios. He had never heard anything like the tone that was beginning to emerge. No wonder his great-grandfather had loved it so much.

“That’s a great flute, J.J.,” said Aengus. “The best I ever heard.”

As J.J. continued warming up the old instrument, Aengus adjusted the fiddle’s tuning to it. He began a jig. After a few more unintentional whistles, J.J. found the tone again and took up the tune. But he was uneasy. His eye fell on Bran, trapped in her death throes for eternity. It was awful, but what was the use in him worrying about her and empathizing with her pain? Why should he cause himself distress when there was nothing, absolutely nothing, that he could do about it?

So he played, one well-loved tune after another, and forgot about everything except the music. He looked up, caught Aengus’s eye, and felt his spirits soar. It’s impossible to smile while you’re playing the flute, so J.J. raised his eyebrows instead and threw in an overblow for a few notes, which made the flute hop up an octave. Aengus whooped with delight and responded with a series of ingenious variations.

With a glance and a nod they changed to a new tune. The two instruments blended perfectly, and the wild, thrilling music rang out over the beautiful land where it had been born.

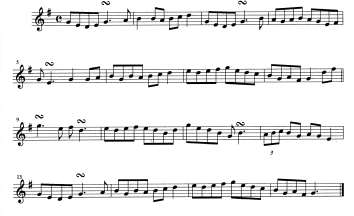

FAR FROM HOME

Trad

“Will we go down to the village?” said Aengus. “See if Devaney caught the goat yet?”

“I don’t see why he has to catch her,” said J.J. “Why can’t he just turn her into a bodhrán from a distance?”

“He did that once. The bodhrán rolled away down the hill and into the sea. He had to go over beyond until it dried out…. He says she did it to him on purpose. He says it’s never been the same since.”

“It sounds pretty good to me,” said J.J.

He took the fiddle, and Aengus hefted the dog into his arms. Together they picked their way down the hillside above the stand of strange red trees where, in his own world, J.J.’s house stood. Aengus began to track to his right, toward the mountain road, but J.J. still wanted to see the place.

“Do you mind?” he asked.

Aengus looked irritated. “It’s just that the dog’s a bit heavy.”

“You can go on if you like, and I’ll catch you up. I won’t be long.” He laughed. “In fact, I won’t be any time at all.”

But when he walked down to the edge of the copse, Aengus went with him. The red trees were tall, with broad trunks and dense, crinkly leaves.

“What are they?” J.J. asked.

“Chiming maple,” said Aengus. “That’s what they were known as in your world, anyway. The last one over there was cut down in 1131.”

“Really? Why?”

“The wood has amazing acoustic properties. Your early churches and minstrel galleries were all lined with it. It had the effect of turning the whole building into a musical instrument. Beautiful,” he said, remembering. “But like all the most wonderful things, it was too much in demand. It made the best musical instruments as well. We call it the bell tree.”

J.J. put his hand on the nearest red trunk.

“Play a few notes there under it,” said Aengus.

J.J. lifted the flute and began to play a tune. The whole tree resonated in sympathy, filling the

air with sweet, ringing harmonies.

“Wow,” he said.

“There’s a guy in your world making fiddles from it,” said Aengus. “He sends one of his apprentices over now and then to get the wood. He lives in Italy, I think. Tony, that’s it. Tony Stradivarius.”

“Not Antonius Stradivarius?” said J.J. incredulously.

“That’s him. I used to have one of his fiddles. I left it behind me somewhere….”

“But he’s been dead for over two hundred years,” said J.J.

“Oh. Has he?” said Aengus. “It’s hard to keep track…. You’re a lot better off over here, you know.”

J.J. played to the tree again, then stopped and listened to the resonances.

“I knew a lovely girl once,” Aengus went on. “I was mad about her, actually. But I went back to visit her again and…well…it was awful. You ploddies just don’t last.”

J.J. was only half listening. It was all very well for Aengus. He could come and go as he pleased between the worlds. It didn’t seem fair that J.J. was stuck here forever.

He walked in among the trees. In their midst was a cottage, very much like the others he had seen here;

more like a hollowed-out lump of rock than a house. It appeared to be quite empty, and he had no inclination to go in. He wandered around the outside, but there was nothing to connect this edifice with the house where he had been born. Nothing, that was, until he came to the spot where the new extension would be standing. There, against the trunk of another of the maple trees, was a little drift of very familiar socks.

He was still there when Aengus came looking for him. “Haven’t you seen enough?”

“Yes,” said J.J. He was following Aengus away from the house when he heard, or thought he heard, music. He turned back and bent his head toward the small, dark doorway. It was faint, but it was definitely there.

“What is it?” said Aengus.

“Music,” said J.J.

“Oh, I doubt it,” said Aengus. “Come on. Let’s go.”

“No. I can definitely hear it. There must be a leak here.”

“You didn’t believe all that nonsense, did you?” said Aengus. “You can’t really hear ploddy music, you know. It’s an old wives’ tale.”

But J.J.

did

hear it. He heard a concertina, then two concertinas. He recognized the tunes. Two jigs that he

had very recently learned. He recognized the playing as well. He had been hearing it all his life.

The charms of Tír na n’Óg abruptly lost their grip. He turned and began to walk purposefully through the trees, back the way they had come.

Aengus hurried after him, still carrying the dog. “Where are you going?”

“Home.”

“Don’t be a fool, J.J.” J.J. didn’t stop. “I’m not such a fool as you think, Aengus Óg. They’re still there. I can hear them. My mother and my sister, playing their concertinas.”

He was out of the trees now and striding, nearly running, up the rocky slope toward the ring fort.

“J.J.! Wait!” J.J. ignored him. Aengus had already tricked him into staying and would probably try to do it again.

“You belong here, J.J.,” he was calling now. But J.J. knew where he belonged, and he wasn’t going to be tricked again. The only thing that would stop him now was if Aengus turned him into a tortoise. Let him. He didn’t care. He was going home.

But Aengus’s next words did, in fact, stop him in his tracks.

“Take Bran with you!”

J.J. waited on the hillside for Aengus to catch up. Of course he would take Bran. He was surprised he hadn’t thought of it himself. He wished he didn’t have to do it, but there was no other way to end her misery. If Father Doherty hadn’t stopped her, she would already have ended it herself.

Father Doherty. J.J. was suddenly less enthusiastic about going through the souterrain wall. He looked at Aengus.

“The priest,” he said. “I suppose there’ll be, you know, remains.”

“Oh, yes,” said Aengus. “Phew. Nasty.” J.J. was uncertain again. Already the lure of Tír na n’Óg was beginning to reassert itself. But for reasons known only to himself, Aengus Óg relented.

“No. He’s gone, J.J. It’s taken care of.”

“How do you know?”

“Someone found him. They took him away. What was left of him.”

“But how do you know?”

“We move easily between the worlds,” said Aengus solemnly. “In the blink of an eye we are gone. In the same blink of the eye we are—”

“Yeah, yeah, yeah,” said J.J. Despite all that had happened, J.J.’s heart warmed toward Aengus again.

“You’d want to watch yourself, you know. You’re beginning to sound like a god.”

Aengus roared with laughter. Together they continued up the hill to the rath, and there, between them, they maneuvered the distressed dog down into the souterrain. In its farthest corner, Aengus helped J.J. to balance her weight in his arms without losing his grip on the candle or the flute.

“Come back and play a tune with me sometime,” he said.

“I will. I promise.”

“You might forget.”

“I won’t. I’ll try not to.”

“Believe the things you remember, J.J. Even if they don’t make sense.”

It’s not easy to hug a young man carrying a wolfhound, but Aengus Óg was a man, possibly even a god, of many talents. J.J. turned to face the wall. He would come again, he promised himself. But the gray dog, who had hunted Fionn Mac Cumhail’s game from one end of the ancient world to the other, was leaving Tír na n’Óg forever.

“Good-bye, Bran,” he whispered, and stepped forward.

THE MAPLE TREE

Trad

Ciaran and Marian were down at the GAA pitch, watching a camogie match. They had tried to persuade Helen to come with them, but she had resisted. She couldn’t face the community that day. Whether or not Father Doherty was mentioned, his discovered remains would be haunting every eye that met hers.