The New Policeman (17 page)

Authors: Kate Thompson

J.J. let out a long-held breath. “It’s only a goat, Bran,” he said. He was used to the wild goats up here on the mountainside. They were a menace to the farmers, but J.J. had a grudging respect for them all the same. They came and went as they pleased, caring nothing for walls or fences, or carefully preserved meadows. On more than one occasion Helen and Ciaran had lost good milkers to the herds that roamed up here, and whenever J.J. saw the wild goats, he thought of them and wondered what their lives must be like away from the comforts of the farmyard, off with the raggle-taggle gypsies.

But were goats here the same? This one certainly

wasn’t behaving like the ones he had encountered here before. They usually kept out of sight, and if he took them by surprise, as occasionally happened, they lost no time in getting out of his way. But this goat was coming toward him. And it was, he now realized, the biggest one he had ever seen.

Bran’s reaction was not inspiring him with confidence. She was clearly terrified of the goat, alternately attempting to protect J.J. with hysterical growling and taking refuge behind him. Ignoring her completely, the huge goat kept coming.

J.J. stood up. The goat stopped about twenty meters away. It had a jaunty, almost humorous expression, as though it might be on for a bit of craic. J.J. hoped that it wouldn’t be at his expense. He had seen more goat horns than most people, but he had never seen a pair of horns that size. They were as thick and as long as his arms, and an awful lot more dangerous.

He would have felt a lot safer behind a large rock or a tree trunk, but he couldn’t move; couldn’t even look around to see where he would run if it turned out that he had to. The goat’s yellow eyes, their narrow, vertical pupils, had him mesmerized. There was a sharp, dangerous intelligence in them. They were full of fun and full of disaster. Bran had given up the

battle with her pride and was cringing behind J.J.’s back.

“I know you,” said a rich, dark voice. J.J. couldn’t tell whether it came from the air around him or from inside his head. “I’ve seen you in here before.”

J.J. was about to reply when Aengus’s words came back to him. “Don’t talk to any goats.”

“Not here, perhaps,” said the goat. “Over on the other side, was it?”

Still J.J. said nothing. The goat’s expression didn’t change, but there was a smile in its voice. “Aengus Óg has been filling your head with nonsense, I see. Well. That’s the way with the sidhe.”

J.J. had almost forgotten the old word for the fairies. It could mean a hill, or the people of the hill. It carried very different connotations.

“Tricky folk,” said the disembodied voice of the goat. “Not to be trusted. Spun you some yarn about a time leak, has he?”

J.J. held his tongue, but it wasn’t easy. The goat frightened him, but it didn’t appear to want to harm him.

“Slipped over beyond, hasn’t he?” the voice continued. “Off flirting with some young one, I’d be willing to bet. A bit of a lad, your Aengus Óg. The

wild Irishman, with his fiddle and his charm and his little bit of magic.”

J.J. was feeling sleepy. He wanted to defend Aengus; he didn’t want to hear any more malicious talk, but there was something about the deep, mellow tones in that voice that made him want to listen.

“Tired?” said the goat. “Awful warm in here, isn’t it?” J.J.’s mind drifted. The green moss, smelling of water, the dappled shadows, the warm sun, the warm voice; they were the things of dreams. His eyelids closed. The dream sounds and smells grew deeper and stronger. But something moved between him and the sun. His eyelids and his skin sensed the shadow.

With a struggle he opened his eyes. The thing that stood in front of him was not a goat. It had horns, cloven feet, but it was towering on two legs; tall as the trees, looming over him.

“Aengus!” he yelled at the top of his voice. Bran found her courage and was at his side, snapping and barking. The thing shrank, became a goat again, stood looking out at them, as quietly confident as ever.

“Do you know what I am?” said the voice.

J.J. almost answered, stopped himself just in time. He was shaking from head to foot.

“Do you know who we are, who walk between the worlds and haunt the wild places of the earth?”

J.J. felt his energy begin to flag again. He was being drawn in by the voice.

“Do you want to know the real magic that is at work in the world?”

J.J. put his hands over his eyes and his ears. He hummed to himself there in the shady woods, and the tune that he hummed was the one his mother had taught him less than twenty-four hours ago.

Something gripped his wrist. He clenched his teeth and resisted with all his might, keeping his eyes and ears closed.

“J.J.!” He heard his name close to his ear and, carefully, peeped out between his fingers. It was Aengus.

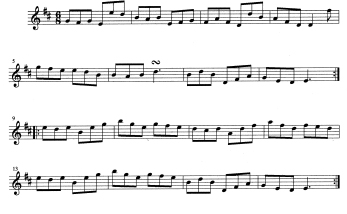

THE WILD IRISHMAN

Trad

Anne Korff, with Lottie at her heels, walked back into the village. J.J. Liddy had not been on the gravel walks or anywhere in their vicinity, and Anne was beginning to suspect that he never had been. She berated herself. She ought to have known better than to trust anything Aengus Óg told her. This was by no means the first time he had sent her on a wild goose chase. She remembered the occasion when he had offered to indulge her passion for sailing by letting her take his sleek little boat, the

Salamanca

, for a sail in the bay. He had whistled up a perfect offshore breeze, which had sent her speeding out past Augnish and around the mouth of the bay. But no sooner had she gone about to begin the return trip than he turned off the wind and dropped an enormous cloud on the surface of the water.

The boats of the sidhe have no engines. It happened before the passage of time was appreciable in Tír na n’Óg, but even so Anne Korff had learned far more than she wanted to know about the insides of clouds.

In the village, between dances, Anne asked Drowsy Maggie if she had seen J.J. Maggie could not tell her where he was now, but she did tell her where he had been when Anne had bumped into Aengus outside Winkles. She stood with Lottie on the harbor wall and looked out to sea. There was no sense at all in tearing off to look for them again; there were far too many places where they might be. She knew the dangers of lingering too long in the land of eternal youth, but she knew, as well, that everything was changing. If things carried on as they were, she might never get a chance to see it in the same way again. Another dance or two would not hurt.

When the musicians started up again, she stepped into the crowd; felt the familiar lightness in her feet and in her heart as all her concerns slipped away. As long as J.J. remembered what she had told him, he would be all right. For the moment, at least, there was nothing more that she could do for his parents.

OUT ON THE OCEAN

Trad

The new policeman phoned in sick during the week and then didn’t turn up for three more days. He didn’t, therefore, come to hear about the latest drama in the village until he presented himself for work on Friday morning. This time there could be no doubt about the case. Thomas O’Neill had joined the ranks of the missing.

He hadn’t been seen since Monday, the day that he had met Garda O’Dwyer on the street. The last person who had seen him was his daughter, Mary, who had met him on his way home from the shops. She was on her way into Galway, and he’d asked her to call in for a cup of tea when she got back because, he said, he had something interesting to tell her. But when she got there, three or four hours later, he hadn’t been

home. Her brother had no idea where he was, and nor had anyone else. Now, four days later, he was still missing. The police had done their work: the harbor had been dragged and the area around the village had been searched. There was no sign, anywhere, of Thomas.

The villagers, already worried, had progressed to a state of panic. They demanded a round-the-clock Garda presence and Sergeant Early promised to supply it. He was less than pleased, therefore, when Larry O’Dwyer arrived in his office at the end of his shift and handed in his notice.

“Why?” he asked him.

“I’m not getting anywhere,” said Larry.

“You’ve only been on the job a few weeks,” said Sergeant Early. “Where did you expect to be getting?”

Larry shrugged. “I’m not cut out for it,” he said. “I thought it was a good idea to join the guards, but it doesn’t seem to be working out the way I expected.”

“That’s great,” said Sergeant Early sardonically. “You have no idea how delighted I am to hear that. Just when we’re in the middle of the worst crisis this part of the country has seen in years, you feel, on a personal level, that it’s not working out for you.”

Larry looked at the floor and counted backward. “Sorry,” he said.

“What was it you expected, anyway?” said the sergeant. “High-speed car chases? Gun battles? This isn’t America, you know.”

“It isn’t that,” said Larry. “I just thought…”

“What did you think?”

“I thought the police knew more than they do. I thought they were good at all kinds of detective work. At least, I think that’s what I thought.”

Sergeant Early stared at Garda O’Dwyer and wondered if he was quite all there. Maybe the Garda Síochána would, after all, be better off without dreamers like him.

“Whatever you think, Larry,” he said. “But it’s a good job, you know. What will you do instead?”

“I have plenty to keep me busy,” said Larry.

“There’s no money to be made out of playing the fiddle, you know.”

“I’m not too pushed about money.”

“You might think differently if you had a wife and kids to support,” said the sergeant.

“I’m sure I would,” said Larry.

Sergeant Early sighed and examined the written notice that Larry had given him. The handwriting was

large and untidy, like a child’s.

“You’ll serve out the month, at least?” he said.

“I’ll do my best,” said Larry.

“Please God we’ll have these disappearances sorted out by then,” said Sergeant Early.

CONTENTMENT IS WEALTH

Trad

“You were lucky,” said Aengus.

They were sitting on a fallen branch. The goat had gone.

“What was it?” said J.J.

“A púka,” said Aengus. “I’m afraid I gave you the wrong advice.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, it was just a joke, really. Don’t talk to any goats. I didn’t really expect you to meet one.”

“So I should have talked to it?”

“Definitely,” said Aengus. “He probably thought you were being extremely rude.”

“What would he have done to me if you hadn’t come along?”

“I’ve no idea,” said Aengus. “But they have powerful

magic, the same púkas. Very old creatures. Much, much older than us. They claim to have been here when the world began. Some of them say that they made it.” He thought for a moment, then stretched himself out along the branch, his hands beneath his head. “I probably should have asked him about the leak.”