The New Policeman (14 page)

Authors: Kate Thompson

“Na,” said Marcus. “Don’t want to spoil Devaney’s fun.”

The barmaid came over with the Coke.

“How much?” said J.J., before he remembered that they didn’t use money.

“No charge for musicians,” said the girl.

Since there was no one in the place apart from musicians, J.J. wondered if Aengus might not be the only person in Tír na n’Óg who hadn’t quite grasped the concept of profit.

“What’s in the yellow bottle?” said J.J.

“I don’t know,” said Marcus, “but it does the trick. Do you know that tune? ‘The Yellow Bottle’?”

“I know a tune called ‘The Yellow Wattle,’” said J.J.

“That’s the one,” said Marcus. “Sometimes the names get mixed up on the way through to your side.”

“Sometimes they don’t get through at all,” said Jennie. “That’s why there are so many tunes that have no names, or that get called after the person who first plays them.”

“Or the people who think they wrote them,” said Marcus.

Aengus arrived with the borrowed fiddle. He clapped his hands and rubbed them together vigorously. “The yellow bottle looks like the order of the day,” he said breezily.

“Hold on a minute,” said J.J. “How to worry, rule number three. No alcohol.”

A flash of anger blazed in Aengus’s clear green eyes. J.J.’s spirits dropped into his boots, and for an instant he was afraid of how Aengus might react. But he was saved by a commotion in the street outside; a sudden burst of bleats and roars, followed by a hollow, knocking sound. Then Devaney came in through the door with the bodhrán.

Everyone let out a cheer. Devaney joined the group in the corner, and Aengus opened Maggie’s fiddle case. He showed no more signs of being annoyed with J.J.

“Let’s see about finding this leak then, shall we?” he said.

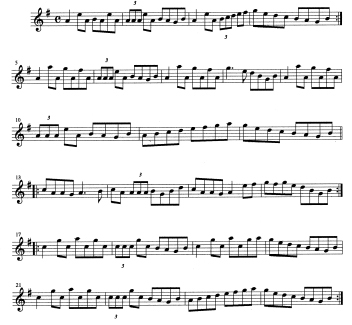

THE YELLOW WATTLE

Trad

There were no musicians playing that night in Winkles, nor in Green’s nor the Auld Plaid Shawl, nor in any of the other pubs in Kinvara. J.J. Liddy was young, but he was one of their number nonetheless. As long as he was missing, there would be no live music heard in their town.

Anne Korff received a visit from Sergeant Early on Tuesday evening. She told him her story, showed him the punctured bike tire, and expressed enormous regret at not having insisted that J.J. take a lift with her. Sergeant Early assured her that she had done nothing wrong and was adamant that she shouldn’t blame herself.

But J.J.’s parents, their neighbors, and half the local

community were out walking the roads and scouring the coastline, and Anne Korff did blame herself. She had been wrong to send the boy on such a hopeless errand. It was high time she fetched him back.

It was difficult to worry while the fairy music was playing, even for J.J., who was a master of the art. As soon as the tunes started flowing, he forgot all about leaks, musical or otherwise, and settled in to enjoy himself.

Gradually the pub filled up. Some danced, some listened and watched, some joined in with hilarious recitations or with songs so sorrowful that there was not a dry eye in the place when they reached their end.

Aengus, under loud and frequent protest, drank nothing but water throughout the session. In his honor the musicians played “The Teetotaller’s Reel” on three different occasions, and they might have played it again had Aengus not become edgy and threatened to turn them all into “something nocturnal and slimy.”

J.J. learned more in that session than he would have believed possible. At least half the tunes that were played he had never heard before, and he had to concentrate hard to pick up their gist. Sometimes,

when he heard one he particularly liked, he asked Aengus or one of the others to go over some of the trickier lines with him. He didn’t expect to have them perfectly, or anything like it, but he knew that he would be able to play along with them if they came up again in sessions. Their names he forgot as soon as he had heard them.

And that wasn’t all that he learned. By the time he had joined in a few sets of tunes he was, Aengus remarked encouragingly, playing like a native. The fairy rhythms and their subtle intonations seemed to be in his blood. He had never felt more at ease with a fiddle beneath his chin. It was as though he had been practicing for this all his life.

But the one thing that J.J. did not encounter that afternoon was a music leak. The others described to him how it happened; how other instruments could be heard, playing faintly in the gap between the tunes and how, if the leak was strong enough, the two groups of musicians, one in each world, could join in each other’s tunes and end up with a mighty session. J.J. would have loved to hear it, but it didn’t happen. No matter how hard he listened, he could hear no notes, corresponding or otherwise, leaking through the time skin.

“It’s very unusual,” Marcus remarked. “Especially in here. It’s a very leaky place.”

“The leakiest,” said Jennie.

Aengus went out to take a stroll and see if there was anything coming through in any of the other pubs. In the street he ran into Anne Korff, who was outside the door talking to Bran.

“How’s life, Lucy?” he said.

Anne laughed. “To tell you the truth,” she said, “it could be better.”

“I’m glad to hear it,” said Aengus. “Are you going in for a pint?”

“No. I’m just going to put my head round the door. I’m looking for someone.”

“Oh? Anyone I know?”

“A young man from our side. J.J. Liddy. I did a very stupid thing. He wanted to buy some time, and I sent him here to see what he could find out. Now his poor mother and father are going demented, searching for him everywhere.”

“The poor things,” said Aengus. “But you’re in luck. He hasn’t gone far.”

“No? You have seen him?”

“Yes,” said Aengus. “He tried to give me ten euro

for our time. I told him if he could find the leak he could have it for nothing. So he went off looking for it.”

“Which way did he go?”

Aengus pointed to the Galway road, which ran out of the village past the castle. “He was heading for the gravel walks when I last saw him.”

“I’ll find him out there then,” said Anne. “Thank you, Aengus.”

“No bother.” Aengus watched Anne until she had disappeared down the main street of the village, then he continued on his way.

It seemed to J.J. that they played for hours, but since his watch wasn’t working, or was working to some harebrained scheme of its own, he had no way of telling. Whenever anyone came in or went out, the doorway filled with brilliant sunlight. There was, he kept reminding himself, plenty of time.

Aengus came and went two or three times during the course of the session, and at one stage J.J. suspected that he was nipping over to Keogh’s or down to Tully’s for a quick drink of something stronger. But if he was, he showed no signs of it, and his playing, which was an education in itself to J.J., didn’t show any ill effects following his absences.

It was Aengus who, eventually, announced the end of the session by putting the borrowed fiddle back in its case. J.J. followed suit.

“You may as well finish up your drink,” he said. “I’ll pop this fiddle back in to Maggie and come back for you. Then we can have a think about what to do next.”

THE GRAVEL WALKS

Trad

J.J. sat down on the footpath beside Bran and leaned against the wall. There was, he noticed, a small puddle of blood beside the damaged leg. Bran squirmed closer and rested her head in his lap. She made no sound, but she fidgeted constantly, finding no comfort. Occasionally a deep shudder ran through her whole body. J.J. scratched her ears and tried not to look at the horrible injury.

The warmth of the day made him drowsy. He surrendered to the feeling and allowed his heavy eyelids to close. The brightness of the sun turned his vision red inside them.

Something was wrong.

He opened his eyes again. Throughout the whole of that long session in the pub the sun had scarcely

moved in the sky. Instinctively he looked at his watch. Six ten. He put it to his ear. Tick…silence…tick.

There was, he finally realized, nothing at all wrong with the watch. He had arrived in Tír na n’Óg at the beginning of time. It had not established itself here yet; had barely disturbed the pristine stillness of eternity. He couldn’t hope to fully understand what was happening, but he was beginning to get an inkling of how it might work, like a force that was slowly gathering momentum. His best guess was that Tír na n’Óg was only receiving a tiny trickle of time. But even this slow leak was far more than his own world could afford to lose.

It meant, at least, that he would probably be home in time for the céilí. Or did it? The uneasy feeling returned. Was that right? Was it only six ten at home? Or was time passing faster there? Another penny was teetering, about to drop, but J.J. was distracted by the sudden appearance of the goat. She sprang out through the door, gave J.J. a look of utter disdain, and bounded off toward the main street.

Bran sighed and turned to lick her wound. J.J. looked away. Maggie came out of her door with her fiddle case. She waved to him and walked down toward the quay. The goat looked up and down the

street, then turned to follow her. There were other people drifting down that way as well, and J.J. wondered if there was going to be another dance. He noticed that one or two of them glanced up at the sky as they went, but other than that he saw no signs of anxiety in the village. How could they be thinking about dancing? Why was everyone not out searching for the leak? Perhaps, whatever Aengus and the other musicians had said, it just wasn’t bad enough here to be worth worrying about. Maybe they didn’t realize how bad things were on the other side? Or didn’t care?

In his imagination he saw a bleak picture: the planet spinning like a tennis ball, its occupants chasing around frantically as they tried to fit their lives into their ever-diminishing time spans. The trouble was, how would they know where to start looking? Even if you were standing right on top of the leak, how would you know? You couldn’t see time, or hear it, or smell it.

Devaney and the others strolled out of the pub.

“Coming down to the quay?” asked Jennie.

“Don’t you think it would be better to look for the leak?” J.J. asked her.

They all looked up at the sky, then at one another, then back at J.J.

“Ah, here’s Aengus,” said Marcus, sounding enormously relieved.

He had appeared round the corner of the street and was coming toward them. The others greeted him briefly, then went on their way to the dance.

“You sure you don’t want to join them?” said Aengus.

“Lesson number four,” said J.J. “No dancing.”

Aengus closed his eyes, and J.J. wondered if he might be hiding another of those angry moments. But when he opened them again, he was as chirpy as ever. “So what’s the plan?” he said.

“I don’t know,” said J.J. “I was hoping you might have one.”

“Not really,” said Aengus. He thought for a moment, then went on, “You’re a farm lad, aren’t you?”

“You could say that,” said J.J.

“You must have spent a bit of time up in the hills and out on the land.”

“I have. Why?”

“Well, did you never come across any kind of a leak?”

“I don’t think so,” said J.J. “I never heard music, anyway.”

“Nothing else?” said Aengus. “You never saw anything that shouldn’t be there or heard people talking?”

“No,” said J.J. But Aengus was getting out his tobacco, and it reminded him of something that had happened when he’d been up in the hazel woods above the farm, searching for a lost goat. “I smelled smoke once, though. Tobacco smoke. And there was no one there.”

“That’s exactly the kind of thing we’re looking for,” said Aengus. “Where was it?”

J.J. told him.

“That’s where we’ll go, so,” said Aengus.

FREE AND EASY