The New Policeman (11 page)

Authors: Kate Thompson

“And I’m Aengus,” the fiddler finished up. “Do you play yourself?”

“I do, a bit,” said J.J. “Fiddle mostly. A small bit on the flute.”

“Great stuff,” said Aengus. “You might play a tune with us.”

“Ah, no.” J.J. was not normally shy to play, but the music he had heard here was subtly different in its rhythms and intonations. He would like to hear more before he picked up an instrument and tried to join in. Besides, he remembered with an effort, he had not come here to play tunes.

“I came across this dog in the street. Do you know who she belongs to?”

All the musicians turned and looked at the dog, which was now stretched at full length along the footpath.

“That’s Bran,” said Jennie.

“Is she yours?”

“She isn’t anyone’s,” said Jennie.

“Someone ought to take her to the vet,” said J.J. “I don’t mind doing it if no one else will.” He only had

ten euros on him and he knew that wouldn’t pay a vet’s bill, but he would cross that bridge if and when he came to it.

“There’s nothing anyone can do for Bran, J.J.,” said Aengus. “You shouldn’t concern yourself with her.”

“Come and play a tune,” said Marcus.

J.J. was horrified by everyone’s attitude toward the dog. He wasn’t sentimental himself; he had grown up around farm animals and had seen them with all kinds of damage. But Bran’s injuries were particularly awful. They needed attention.

“I didn’t come here to play tunes,” he said, a bit more irritably than he meant to.

“Oh?” J.J. thought he glimpsed a corresponding gleam of antagonism in Aengus’s clear green eyes, but if he did, it vanished as quickly as it had arisen. “What did you come here for, then? A rescue mission for lame dogs?”

“No,” said J.J.

“You have another reason for being here, so,” said Maggie, who wasn’t asleep after all.

“I have, I suppose,” said J.J., although the business with the dog had almost driven it out of his mind. It seemed absurd now, as he said it. “I was told you might be able to help me buy some time.”

“Time?” said Devaney.

“No bother,” said Aengus.

“We’ve heaps of it,” said Cormac, “and we’ve no use for it at all.”

“Oh, great,” said J.J., though it all seemed even more absurd now. “Will you sell me some, then?”

“Take it,” said Aengus. “Take it all.” J.J. was silent, trying to make sense of what he was hearing.

“We don’t want it,” Aengus went on. “You’re welcome to it.”

“You mean…” said J.J. “You mean…just take it?”

“Just take it,” said Aengus.

J.J. looked around at the other faces, wondering what kind of joke was being played on him. There was no sign that he could see of any malice or amusement. But it couldn’t possibly be as simple as it appeared to be.

Devaney sensed that he was in difficulty. “Wait, now,” he said. “Maybe it would be better if he gave us something for it.”

“It would,” said Maggie. “It would cement the deal.”

“And he would have more value on it, that way,” said Marcus.

“Right, so,” said Aengus. “Make us an offer for the lot.”

J.J. felt the ten-euro note in his pocket. If he’d known he was going to be in this situation he would have come better prepared. He wished he’d had the foresight to ask Anne Korff for a loan.

He took it out. “This is all I have on me.”

They all stared at the shabby note in his hand. It was a mistake, he knew. He had insulted them.

“I can get more,” he said hastily. “I have a couple of hundred in the credit union.”

“Ah, no,” said Cormac. “It isn’t that.”

“You could wave any amount of that stuff around in front of us,” said Jennie.

“It’s no use to us,” said Maggie.

“We don’t use it,” said Devaney.

“Have you nothing else?” said Aengus.

J.J. searched his pockets. In the inside breast pocket of his jacket he had the candle and matches that Anne Korff had given him. He needed them for his way back. His penknife was in there as well, but he was very attached to it. If he had to he might offer it, but it would have to be a last resort. He searched his other pockets.

Aengus looked up at the sky. Devaney examined his

drum skin and gave it a couple of hefty clouts. Maggie appeared to go to sleep again.

“There must be something,” said Devaney.

“I’m sure there is, if we could think of it,” said Jennie.

“There is,” said Aengus. “There’s something we all want.”

“What?” said J.J.

“‘Dowd’s Number Nine.’”

“Yes!” said Maggie, who wasn’t asleep after all.

“Good thinking,” said Cormac.

J.J. racked his brains. It was a common enough tune—so common, in fact, that there were endless jokes about its name. There was no “Dowd’s Number Eight” or “Dowd’s Number Ten,” no “Dowd’s Number One” or “Two,” or any other numbers at all. Just “Dowd’s Number Nine.”

J.J. knew he played it. It was one of Helen’s favorite tunes. There were dozens, possibly hundreds of tunes that J.J. could play if they came up in a session, but the problem was that he seldom remembered their names. Unless he was playing in a competition it never seemed important to him.

“Don’t you know it?” said Aengus, sounding disappointed.

“I do,” said J.J. “I just can’t think of it. How does it start?”

“That’s what we want to know,” said Maggie.

“We used to have it, all of us,” said Marcus. “It slipped our minds. We’d love to get it back.”

“It’s a great tune,” said Devaney.

“One of the best,” said Jennie.

J.J. thought hard. The tune was associated with Joe Cooley, the great South Galway accordion player. It was on the album that had been recorded during a pub session shortly before he died. Helen had it on in the house constantly. J.J. knew it backward.

Aengus offered him the fiddle. J.J. took it, thought about the CD, tried a tune.

“That’s ‘The Blackthorn Stick,’” said Devaney.

J.J. tried another.

“‘The Skylark,’” said Maggie.

J.J. wrung his memory again, but nothing else would come to him. “I have some nice Paddy Fahy tunes,” he said. “I could teach you one of those.”

Jennie giggled. Aengus shook his head. “We have all Paddy’s tunes,” he said.

“He got them from us, actually,” said Cormac.

“He wouldn’t like to hear you say that,” said J.J.

“Why wouldn’t he?” said Aengus. “He’d be the first

to admit it if he thought anyone would believe him.”

J.J. wasn’t sure, but he wasn’t about to argue the point. “I got a nice jig the other day,” he said.

“Let’s hear it,” said Aengus.

J.J. started to play his great-grandfather’s jig. After the first couple of bars the others joined in. J.J. was about to stop, since it was obvious that they knew the tune, but it was lovely playing with them. Once through the tune and he was beginning to hear the accents and slurs that gave their playing its distinctive lift. By the third time through he was beginning to adopt it into his own bowing. He caught Maggie’s eye and changed to the second of the tunes that Helen had taught him the night before. The others knew that one, too. When it came to an end, Aengus took back the fiddle.

“You’re a lovely player,” he said. “But you would wear out the hairs on my bow before you came up with a tune that we didn’t know.”

“They all come from this side,” said Marcus.

That was what the old people had believed. Could it be that they were right? But not all the tunes, surely. Paddy Fahy wasn’t the only composer of new tunes. There were loads of others.

“I wrote a tune myself once,” said J.J.

“You didn’t,” said Maggie. “You just think you did.”

“You heard us playing it,” said Devaney, “and you thought you were hearing it inside of your own head.”

“It happens to lots of people,” said Jennie.

“Play it,” said Aengus.

J.J. lifted the fiddle and played the first few notes. The others were on to it in a flash. J.J. stopped and handed back the fiddle.

“I don’t believe it,” he said. “It isn’t even a good tune.”

“Not all of them are,” said Maggie.

“If it was,” said Marcus, “someone else would have taken the trouble to steal it from us long before you did.”

“Ah, now,” said Aengus. “We don’t consider it stealing.”

There was a small silence, broken by a faint bleat that J.J. thought came from the bodhrán. Devaney clouted it a few times, which appeared to shut it up. J.J. looked around for the goat. There was no sign of it. His attention returned to the matter of “Dowd’s Number Nine.”

“No other tunes you’ve forgotten, I suppose?” he said.

They all shook their heads.

“I tell you what,” said Maggie. “Why don’t you take the time anyway? You can owe us ‘Dowd’s Number Nine.’”

“Brilliant,” said Aengus, and all the others agreed enthusiastically.

“Great,” said J.J. “I’ll learn it from Mum and come back with it.”

“And if you don’t,” said Cormac, “can’t one of us come over and get it from you?”

“No,” said Maggie. “We tried that before, don’t you remember?”

“So we did,” said Cormac.

“That’s the trouble with going over to the other side,” said Devaney. “As soon as you get there, you forget what it was you were looking for.”

“I won’t forget,” said J.J. “I’ll write it down on my hand. I’ll bring it back.”

“Mighty,” said Marcus.

“Sorted,” said Maggie.

“Off you go, so,” said Aengus. “Take all the time you want.”

J.J. stood up, delighted with himself. The others stood up as well, putting down their instruments and shaking hands on the deal.

“OK,” J.J. said. “So how do I take it?”

“Don’t you know?” said Maggie. “No,” said J.J. expectantly.

One by one the others sat down again.

“Nor do we,” said Devaney.

“I thought there might be a catch,” said Aengus.

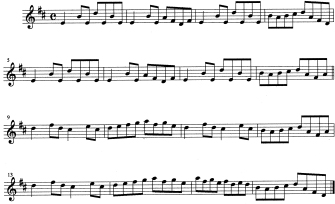

DROWSY MAGGIE

Trad

Helen was angry with J.J. If she hadn’t been, she might not have left it until dinnertime the following evening before she rang the Dowlings to find out if and when he was planning to come home. When she discovered that he wasn’t there and hadn’t been clubbing either, she flew into a panic. She interrogated Marian until she reduced her to tears, then phoned around to all J.J.’s current and former friends. No one had seen him.

“Perhaps it’s a girl?” said Ciaran.

“He’s only fifteen!” said Helen.

“So what? So were Romeo and Juliet.”

“He hasn’t eloped, Ciaran!” Helen snapped.

“There’s no need to take it out on us!” Ciaran snapped back. “He’ll probably walk in that door any moment with a perfectly rational explanation for where he’s been.”

They all agreed that he probably would, but the conviction didn’t last long. Marian blamed herself for telling Helen that he’d gone clubbing. Helen blamed herself for leaving it so late to ring the Dowlings. Ciaran got tired of listening to them both blaming themselves and went for a drive around the village. He was certain that he’d find J.J. there, or on the road home. But when he came back without him, Helen’s optimism had run out.

“This just isn’t J.J.’s style,” she said. “I’m sure something has happened to him. I’m calling the police.”

Sergeant Early took Helen’s call. She gave him the background to what had happened and a description of J.J. and the clothes he had been wearing when they’d last seen him. He promised to send the details out to all the officers in the area. An hour later he arrived at the house and took fuller statements from all three of them. He made a particular point of enquiring about J.J.’s state of mind. Was he happy at school? Did he have friends? A girlfriend? Had he ever taken a drink or, to their knowledge, any kind of drugs? Had he had a disagreement with any of them before he left?

When he had finished, he closed the notepad and

put away his pen. “I’d try not to worry too much if I were you,” he said. “Ninety-five percent of people reported missing turn up within forty-eight hours.” On the front doorstep he hesitated. “This house is famous for its music,” he went on. “I heard your mother play many’s the time, and yourself as well, Mrs. Liddy.”

Helen ignored the “Mrs.” “Music runs in the family all right,” she said.

“I play a bit myself,” said Sergeant Early. “Banjo. I couldn’t live without it.”

“I know how you feel,” said Helen.

As he closed the door behind him, Ciaran said, “Jaysus. Can you believe it? They’re all at it. The Garda Síochána Céilí Band!”

The sergeant’s reassurances had done little to allay Helen’s fears. There had been two disappearances from the Liddy house in as many generations, and on neither occasion had the missing person turned up. The sergeant’s questions about J.J.’s mental health had put worse thoughts into Ciaran’s head. The rate of teenage suicides in the country was soaring. While Helen started the milking and Marian listened for the phone, he made a quiet, thorough search of every building on the farm.

THE ONE THAT WAS LOST