The Oxford History of the Biblical World (32 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

The description of this era in the book of Judges includes features that are probably authentic to premonarchic Israel: the lack of centralization in the society in religious, political, and military matters and the concomitant lack of a permanent administration, including a standing army. These features clarify one of the most interesting aspects of the period of the judges as presented in the biblical text: the heroes themselves are often unlikely. Such unpredictable leaders more commonly emerge in a society and a time with little or no central organization, when no one is waiting to take the reins. In these contexts, women and outcast men can seize power that would be beyond their reach in a society ruled by a hereditary elite. The theological interpretation of this lack of predictable organization and of the noticeable inappropriateness of many of the era’s leaders was that Israel’s only true leader was Yahweh, and that a battle that Yahweh approved of and therefore fought in on Israel’s side was of course won—but won by Yahweh, not by Israel’s leaders and warriors.

The first leader we meet in this era, after Joshua and the elders of his generation have died (Judg. 2.6-10), is Othniel, a nephew of Caleb, a hero of the preceding era. Othniel’s claims to fame are that he wins a wealthy wife (his cousin) in battle, and he wins the first battle described in the book of Judges as a true judge’s battle, a battle sparked by a “charismatic” leader: the “spirit of Yahweh” came upon Othniel, and he “judged” Israel (Judg. 3.10). In other words, Othniel became Israel’s leader not because he was the next-in-line of some hereditary or administrative hierarchy; rather, he led Israel by exhibiting identifiable and unambiguous signs of being the person who could succeed. The text identifies those signs as the spirit of Yahweh,

although no detail is given. This is what the sociologist Max Weber meant by charismatic leadership—leadership that is not predictable according to any arbitrary scheme, but stems from the force of the leader’s personality alone. The description of Othniel and his battle, however, is so brief, and the language of the description so close to DH’s generic description of the era, that the narrative of Othniel’s career gives little information about the judges’ functions or position, or about the era itself.

The next leader mentioned, Ehud (Judg. 3.12-30), is remembered for his craftiness in killing the enemy king, and for his left-handedness. The quintessential man of the hour, he is the one who can get the job done, and that alone qualifies him for leadership. His most effective battle strategy is to kill by deceit the king of the enemy Moabites, and then he is able to convince Israelite fighting men from the hill country of Ephraim to follow him in cutting off and killing the Moabites fleeing back over the Jordan River. Shamgar (Judg. 3.31) is simply remembered for slaughtering many Philistines, practically bare-handed.

These first three judges were leaders not because they inherited or trained for the position, but because they proved themselves up to the task. Although we are often given their fathers’ names and their home territories, they were not part of an ongoing chain of centralized command. Only their success counted.

Deborah’s story, told twice in Judges 4 and 5, is paradigmatic. She is a woman who wields her power from, we assume, her home territory (4.5), in a local position. We are given her husband’s name, but no other information about him. She seems to hold her power because of her abilities as a prophet. In a later era in Israel, she would not have had the power to call out the army—to be the person with supreme authority in a time of crisis—because by then a hereditary, all-male monarchy ruled. (Athaliah’s brief reign in ninth-century

BCE

Judah is considered an aberration by the biblical authors; see 2 Kings 11; 2 Chron. 22.10-23.21.) But in the era of the judges, Deborah is described as the person with a link with the divine world, and so it is she who calls up the troops when Yahweh approves of the battle (Judg. 4.6-9). And she is not the only female deliverer in this story: another woman finishes off the enemy general. When Deborah predicts to Barak that he will not win the glory of this particular battle because Yahweh will give Sisera over to a woman, we assume she is talking about herself; but we later find that it is Jael, a different woman and at that one only marginally connected with Israel, who will be remembered as the “warrior” who took down Sisera.

The same story is told in Judges 5, in one of the oldest pieces of literature in the Bible. In this poem it is the stars and the Wadi Kishon who actually fight the battle on behalf of the Israelites (5.19-21), further indication that charismatic leadership in Israel was tied to the belief that it was not the human Israelites who determined the outcome of their military engagements, but, on a different plane, Yahweh and his “host” (natural and celestial elements) who fought and won the battles.

The next deliverer, Gideon, confesses himself to be a far-from-impressive character when Yahweh (represented by a messenger) comes to call him to lead Israel to victory against Midian. In Judges 6.15 Gideon protests that his clan is the poorest in Manasseh and that he is the least significant member of his extended family (Hebrew

bêt ’āb,

meaning literally “father’s house”). The theological meaning of this motif is clearest here in Gideon’s story, for Yahweh’s answer is “but I will be with you” (6.16;compare Exod. 3.12).

Later, we are told that Gideon must pare down the size of his army before going to battle (7.2-8), so that Israel will know that it is Yahweh who wins their battles and not their own prowess. Toward the end of Gideon’s story we see the beginnings of a longing for a more stable ruling system, when the people ask him to set up a dynasty. Although Gideon refuses, his son Abimelech takes advantage of this sentiment to have himself declared king in Shechem. His reign is short-lived, and we return for a while to an era of judges instead of kings.

The next judge about whom we have a narrative is Jephthah. As an illegitimate son and an outlaw, he too is in an inferior position until he proves to be the one to whom the Gileadites can turn for military help in a crisis (Judg. 10.18). Judges 11.8-9 makes clear that the basis of Jephthah’s leadership position in Gilead is his military success over the Ammonites, not any office he has inherited or been trained for. There is no such permanent office; the elders of Gilead have no one else to help them in the emergency, and so they agree to appoint the outlaw Jephthah as their head if he is successful.

The accounts of the five minor judges in 10.2-5 and 12.8-15 all contain the phrase “after him” (or “after Abimelech” in the case of the first one, Tola), but this does not mean they were part of a line of rulers or had been trained according to any administrative process. For three of them no patronymic is given—another sign of inferior status. We have the father’s name for Tola and Abdon, but neither father is said to have ruled or judged before his son. Rather, “after him” implies precisely the opposite: that the rule went from competent ruler to competent ruler, regardless of family or place of origin.

Since they are so different from the stories of the other judges, the Samson narratives (Judg. 13-16) should be viewed as a separate piece within Judges 1-16. Samson’s battles are personal, not on behalf of a larger group, and he does not deliver Israel as a whole (despite the promise in 13.5), except by his killing or being a nuisance to large numbers of Philistines. His stories are probably inserted where they are in the book of Judges because they involve the friction between the Philistines and tribe of Dan that arose during this period; this also sets the stage for the conflict between the Philistines and all Israel that is the focus of much of 1 Samuel. However folkloric the narratives about Samson are, they also describe a time of no central authority—a time, instead, of a dependence on individual strength or charisma to overcome Dan’s Philistine enemies. Samson’s shortcomings are obvious: he

is

impetuous and none too intelligent, another unlikely leader in this era of opportunity. The ancient Israelite audience, and we as readers, have no trouble understanding that Samson’s heroic acts would be utterly impossible without the support of Yahweh. The more unlikely the hero, the more understandable the message that it is Yahweh who rules.

Following the deliverer stories in Judges 1-16, chapters 17-21 also portray a time with no central authority. There are not even local leaders—no individual is described as a “judge” or a deliverer (see 18.28). Rather, it is a chaotic period, in which the conflicts are among Israelites: the Danites versus Micah in chapter 18, the men of Gibeah versus the Levite and his host in chapter 19, the rest of Israel versus the tribe of Benjamin in chapter 20, the Israelite army versus Jabesh-gilead in 21.8-12, and

Benjamin versus the women of Shiloh in 21.1-23. The one individual who musters the militia for battle is the nameless Levite of chapters 19-20, and ironically this is the only occasion in the entire book that all Israel unites for war—but against one of their own rather than an external enemy.

Outside the book of Judges, the first few chapters of 1 Samuel reveal the beginning of attempts to establish lineages of power within this premonarchic society. It is assumed that the sons of the priest Eli will succeed him in the priesthood, that he is part of a priestly family that transmits the priestly offices from father to son. Such a process is consistent with passages in Exodus through Numbers (such as Exod. 28.1, 41; Lev. 8; Num. 3.3) that establish a hereditary priesthood, but there is no evidence of such an organization in the book of Judges, and it may not have existed in that decentralized era. (The passages just mentioned come from the Priestly source of the Pentateuch, and although they purport to be about premonarchic times, their date is late in the monarchy at the earliest.) Eli is said in 1 Samuel 4.18 to have “judged Israel” for forty years, and so his sons could also have been considered judges. Along with their hereditary priestly roles, then, they might have filled what had become hereditary administrative or ruling offices.

Samuel’s sons, too, were expected to follow in his footsteps, and in his case what they would have done was to rule or “judge” Israel. In 1 Samuel 8.1-2, Samuel appoints his sons judges “over Israel” in Beer-sheba. The people ask Samuel to bypass his sons because they are corrupt. The very request, however, assumes that judging had become a hereditary occupation by this time. The request for a king to rule over them formalizes the actual situation: the judge was no longer a charismatic, ad hoc leader, but a member of a family line, predictable by birth rather than talent. Calling such a person a king is the next step.

The book of Ruth seems to provide evidence about the premonarchic period. The story is set “in the days when the judges judged” (Ruth 1.1), and there is neither king nor central organization in the story. But much suggests that the book comes from a later period: several features of its language, the explanation in 4.7 of the custom of the redemption around which the end of the story revolves, and the denouement that traces the roots of the Davidic monarchy. So the book of Ruth may tell us nothing about the era of the judges beyond what an Israelite storyteller of a later period knew of it, but even that is worthwhile information. No competent storyteller would place a king in the era of the judges, so a decentralized society is no surprise; but we also learn that that storyteller saw the premonarchic era as a time when life revolved around the village and the family, and when decisions about property and caring for the poor were made on the basis of kin relationships. Naomi and her family, who are Israelites, move freely between Judah and Moab during the famine, and no army or national government interferes. Intermarriage between Israelites and foreigners is presented as an unremarkable experience, but religion does seem to be a “national” matter or a matter of ethnicity. In the famous passage in Ruth 1.16, the Moabite Ruth ties Naomi’s god to her place and her people, and Ruth’s impending trip from Moab to Israel apparently prompted her conversion. So even though the book of Ruth must be used cautiously, its picture of the premonarchic era conforms to modern expectations of a segmentary tribal society.

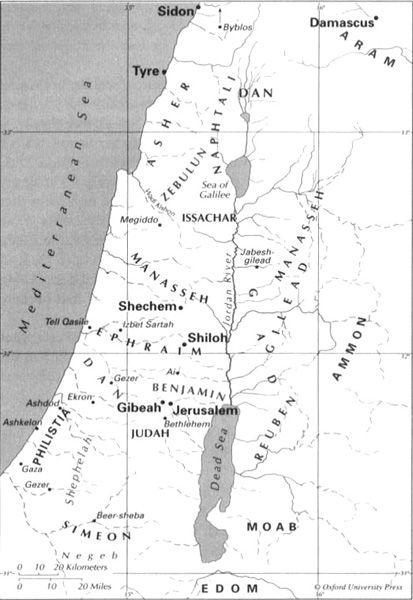

Palestine and Transjordan in the early Iron Age, showing the territory assigned to the twelve tribes of Israel.

A closer look at several aspects of the biblical narrative will help us better understand the era of the judges. The chronological scheme, particularly in Judges 3-16, might enable the dating of some of the events. Unfortunately, however, this chronology is artificial and formulaic. The framework of the deliverers’ stories presents the judges as succeeding one another, although the order of the stories is more likely based on a south-to-north (and then east) geographical model, at least to a point, and so the chronological indications may be secondary. The second list of minor judges (Judg. 12.8-15) spoils the geographical scheme, but as we will see, these two lists (the first is in 10.1-5) probably had a separate transmission history from the narratives around

them and were inserted secondarily into the text after the other stories had been gathered together in geographical order.