The Oxford History of the Biblical World (93 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

While the Jews and the Jesus followers lay at the mercy of the divine emperor’s moods, Gaius’s pretensions were also infuriating to more powerful members of society. After less than four years as emperor, Gaius Caligula was assassinated by soldiers of the Praetorian Guard assigned to protect him.

When Gaius Caligula died in 41

CE

, some in the Roman senate sought to restore the republic. The military, on the other hand, saw an advantage in having only one ruler if he could be easily influenced. Having eliminated the uncontrollable Gaius, the Praetorian Guard felt that they had found a potential puppet in his fifty-year-old uncle, Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus. The troops took Claudius to their camp and declared him to be emperor. Eventually the senators capitulated and voted power to Claudius, who began a thirteen-year reign that would be more productive than either the senate or the army had anticipated.

After voting appropriate honors and titles to the new emperor, the senate attempted to dishonor Gaius Caligula officially. Claudius blocked this legislation, but on his own removed the name and image of his predecessor from all civic records. Remembering the reasons for Gaius’s downfall, the new emperor was especially careful about accepting honors that could be construed as excessive. In a letter to the citizens of Alexandria in Egypt, Claudius responded to the offer of honors by accepting some, such as a formal celebration of his birthday and statues erected to his family and to the peace secured by his reign (

Pax Claudiana),

but rejecting others. He adamantly refused the dedication to him of temples and priesthoods, saying that these were to be reserved for the gods. Claudius thus showed both an awareness of his own humanity and a respect for the consequences of claiming excessive honors.

This letter (

Corpus papyrorum Judaicarum

II153) illustrates the carefully balanced power relationships that held together the empire. When Claudius came to power, governing bodies in provincial cities like Alexandria rushed to show loyalty to the new emperor. After passing various honorific decrees, leaders in each city would send representatives to pay tribute and pledge support. It remained for the emperor to endorse these gestures, thereby ratifying the local actions. Through this reciprocal action, the emperor established a reliable contingent of powerful persons in the main cities, which in turn hoped to ensure future benefactions from the emperor.

This relationship made the cities dependent on the emperor’s approval for many of their actions. In his letter, Claudius responds to other questions that the Alexandrians raised about the local political and social structure. One concerns the institution of a lottery system for selecting priests for the temple of the deified Augustus. Ever since Augustus’s postmortem deification, cities had set up sacred structures and instituted religious rituals to honor the divine Augustus. At the same time, various religious rites involving the emperor were an important means of articulating the mutual relationships that held the empire together.

The structures, statuary, and other images associated with the emperor tangibly

represented Roman power, even in distant provincial cities. At the same time, the rituals associated with the emperor allowed people to demonstrate their loyalty and pay honor to the power of Rome as manifested through the emperor. Priests of the divine Augustus stood at the intersection of this relationship, mediating the bonds of loyalty and patronage. As such, the Augustan priesthood was a highly significant and coveted position in the city. Citing earlier practice, Claudius stipulated that the priest should be chosen by lot, eliminating the possibility of divisive competition or the monopolization of the office by powerful families or groups.

The letter from Claudius to the Alexandrians also sheds light on a long-standing social conflict involving the Jewish population in the city. Representatives of both parties had defended their actions before the emperor, but Claudius was upset with everyone involved, and he used harsh language to express his anger. Claudius affirmed the rights of the Jews, who had lived in the city for many years, and, citing precedent from Augustus, insisted that they be allowed to follow their traditional religious customs. On the other hand, he reminded the Jews that they were aliens in the city, and warned them against trying to participate in civic functions where they were not welcome.

Apparently, some Jews were attempting to improve their status by joining in games and other activities. This intrusion prompted some Alexandrians to attack the Jewish community, at times violently. Claudius threatened to punish both sides if the dispute was not resolved, but he imposed extra restrictions on the Jews. Most notably, in order to relieve the xenophobic fears of the Alexandrians, the emperor prohibited further Jewish immigration into the city. These actions illustrated the Roman desire to maintain order, whatever the cost. Unlike Gaius Caligula, Claudius displayed no animosity toward the Jews or their religion, but he would not tolerate any activity that might upset the social order in this important provincial city. The same lack of tolerance is demonstrated in an incident involving Claudius and Jewish residents of Rome.

The second-century historian Suetonius notes in passing that Claudius expelled the Jews from Rome because of a continuous disturbance caused by

Chrestus (Claudius

25). It is possible that this refers to conflict within the Jewish community over the claims that Jesus fulfilled expectations for the anointed one, the Messiah, or

Christos

in Greek. If so, then by the mid-40s

CE

the Jewish population of Rome included some followers of Jesus. Exactly how the message of Jesus reached Rome is not clear. It may have been brought by missionaries, or by Jewish members of the movement who traveled or relocated to Rome. Apparently, these Jesus followers were willing to argue for their belief, creating a disturbance in the Jewish community and in the capital city. Moreover, if

Chrestus

does refer to Christ, this is the earliest reference to the activity of the Jesus movement outside Christian literature. The report is sketchy, but Suetonius seems to be describing a dispute involving the Jewish community, with no mention of the problems associated with Gentiles joining the churches.

For most Jews, Jesus had simply not lived up to what Jewish scriptures predicted for the coming Messiah. Jewish followers of Jesus, however, read many biblical passages as prophecies that Jesus had fulfilled. Those who did not see Jesus as the Christ were not persuaded by such interpretations. They remained unconvinced by promises that Jesus would return to earth to complete the messianic work of setting up God’s kingdom. This disagreement about Jesus as Christ was the fundamental difference that eventually isolated the Jesus followers from Judaism, and caused the creation of a separate religion known as Christianity. During the reign of Claudius (41–54

CE

), however, this complete separation still lay in the future. Claudius did not care at all about the details of the dispute over

Chrestus,

but once it led to social disorder, he acted swiftly and decisively to end it. The report by Suetonius may be exaggerated, but the expulsion order it describes was well within character for a Roman emperor.

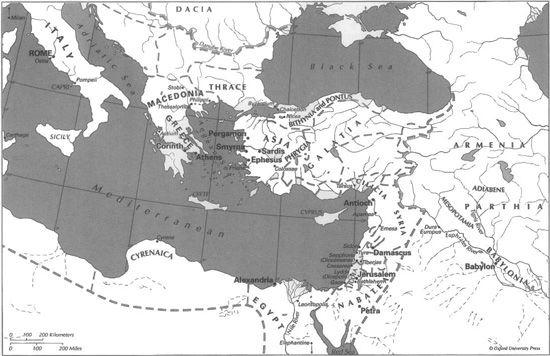

The Eastern Mediterranean during the Roman Empire

After a reign that included many effective and harsh efforts to maintain order, Claudius died from other than natural causes. Agrippina, the wife of Claudius and mother of Nero, was the prime suspect, accused by Roman historians of assassinating her husband with poisoned mushrooms. Nero came to power and shortly thereafter eliminated his one rival, Britannicus, Claudius’s fourteen-year-old son.

Neither Tiberius nor Gaius had been deified after death, but the senate recognized Claudius as a god despite opposition. After the senate’s action, someone—probably Seneca, the philosopher and teacher of Nero—wrote a satirical account of Claudius’s deification. Known as the

Apocalocyntosis

(“pumpkinification”), this imaginative piece recorded a controversy among the gods as to whether the newest god, Claudius, should be admitted to the heavenly court. After rancorous debate, the divine Augustus himself spoke against Claudius because of his murderous cruelty, and the gods dispatched Claudius to Hades to stand trial for his crimes.

Nero came to power amid great hopes. A Greek document from Egypt records the proclamation announcing the death of Claudius and painting an optimistic picture for the reign of his successor: “The Caesar [Claudius], god manifest, who had to pay his debt to his ancestors, has joined them, and the expectation and hope of the world has been declared emperor, the good spirit of the world and source of all things, Nero, has been declared Caesar. Therefore, wearing garlands and with sacrifices of oxen, we ought all to give thanks to all the gods” (

Papyrus oxyrhynchus

1021). By the time of Nero’s accession, the imperial family was poised to ensure smooth transition of power after the death of an emperor. This kind of proclamation was meant to reassure people all around the empire and to begin the immediate shift in loyalty to the next Caesar. In spite of the treachery surrounding the death of Claudius, Nero began his reign by paying homage to his predecessor in ritual acts and by new coin issues. Nero wanted to emphasize his connection to the divinized Claudius, although he was now free to rule as he liked.

In the proclamation, Claudius is referred to as god manifest, and Nero is called “good spirit of the world and source of all good things.” The term

spirit

here (Greek

daimon)

refers to a wide range of semidivine entities thought to be present in the world. The same word is used in the Gospels to describe the evil spirits cast out by Jesus, but here it is specified as a good spirit and applied to the new emperor. Most likely the reference is to the divine element (Latin

genius)

perceived to be part of Nero’s makeup.

Initially, the seventeen-year-old Nero seems to have lived up to the high hopes of his admirers, missing no opportunity “for acts of generosity and mercy” (Suetonius,

Nero

10). Before long, however, the people’s confidence in the new princeps was shattered. Shortly after coming to power, Nero began to devote much of his time, effort, and treasury to fulfilling his desires for music, theater, and sport. He took advantage of a trip to Greece to compete in contests of all sorts against the greatest of Greek performers and athletes. Not surprisingly, the emperor won all the contests he entered, receiving the prize for a chariot race even when he fell out of his vehicle and did not reach the finish line (Suetonius,

Nero

24.2).

So anxious were the Greeks to please the emperor that they rescheduled contests, including the Olympics, to permit him to participate in all of them during his visit. The cities of Greece also poured out lavish honors on the emperor. In Athens, an inscription in large bronze letters was affixed to the architrave blocks on the east side of the Parthenon (

Inscriptiones Graecae

II

2

3277). Thus, the most famous structure in all of Greece now served as a signboard to honor “the emperor supreme, Nero Caesar Claudius Augustus Germanicus, son of god.”

After winning his sham victories in Greece, Nero returned triumphantly to Rome and continued his performing career at the expense of other duties. The extent of Nero’s distraction is captured by Dio Cassius, who tells how Nero was responsible for the destructive fire that ravaged the city for nine days during the summer of 64

CE

. To emphasize his point, the historian describes Nero standing on the roof of the palace singing and playing a small harp, or cithara (Dio Cassius 62.18.1).

Nero was suspected of setting the fire to create open space for his building projects. The most striking part of the “new city” created in the aftermath of the fire was an extravagant palace complex. The Golden House, as it was called, was really a spacious country villa covering 50 hectares (125 acres) in the middle of the crowded city. Suetonius is both awed and disgusted by the structure that demonstrated how “ruinously prodigal” Nero was:

The courtyard was of such a size that a colossal image of Nero, 120 feet high, stood in it, and so wide that it had a triple colonnade a mile long. There was a pond, like a sea, with buildings representing cities surrounding it; and various landscapes with tilled fields, vineyards, pastures, and woodlands, and great numbers of every kind of domestic and wild animal.

Underlining his contempt, Suetonius reports that Nero dedicated his new structure by saying that “he was finally beginning to dwell like a human being” (

Nero

31).

Although the Golden House was never completed, Tacitus makes it clear that the building had a tremendous impact on the long-term development of Roman architecture (

Annales

15.43). The immediate impact on the city, however, was devastating, and the people of Rome held Nero responsible for the blaze. In the early second century Tacitus wrote that to deflect blame, Nero accused a group of people, “known for their shameful deeds, whom the public refers to as Christians” (

Annales

15.44).