The Oxford History of World Cinema (29 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

Frank Borzage (1894-1962)

The son of an Italian stone mason, Frank Borzage was born in Salt Lake City. One of

fourteen children, he left home at fourteen to join a travelling theatrical troupe and soon

became a member of Gilmour Brown's stock company, playing character parts in mining

camps throughout the West. In 1912 Borzage went to Los Angeles, where producer-

director Thomas Ince hired him as an extra, then leading man in two and three-reel

Westerns. In 1916, he began directing films in which he starred; two years later, he gave

up acting for directing.

Borzage's early films as actor/director explore characters and situations that recur in his

later work. As Hal, the dissolute son of a millionaire in Nugget Jim's Partner ( 1916), a

drunk Borzage argues with his father and hops a frieght car which bears him to a western

mining town. Here he encounters Nugget Jim, rescues Jim's daughter from her dreary life

as a dance hall girl, and creates with them an idylic world of their own. Slightly-built and

curly-headed, Borzage conveys the innocence, energy, and optimism that became the

trademark of Charles Farrell's performances for the director in 7th Heaven ( 1927), Street

Angel ( 1928), Lucky Star ( 1929) and The River ( 1929).

Charles Farrell ('I'm a very remarkable fellow') with Janet Gaynor in a scene from Seventh Heaven ( 1927)

Borzage's origins inform a number of his films set in lower and working class milieux.

His first major success was an adaptation of Fannie Hurst's

Humoresque

( 1920), which

describes the rise to fame of a young violinist from the teeming Jewish ghetto on New

York's lower east side and his efforts, as wounded war veteran, to recover his ability to

play again. The love story of Seventh Heaven which earned Borzage the first Academy

Award for Best Director and which

Variety

labelled the 'perfect picture,' involves the

rescue of a gamine of the Parisian streets by a sewer worker, Bad Girl ( 1931), another

Oscar winner, was a work of tenement realism, favourably compared to Vidor's Street

Scene ( 1931) by contemporary critics, exploring the mundane routines of courtship,

marriage, pregnancy, and birth, and celebrating the triumphs and tragedies of an average

young couple.

Borzage specialized in narratives dealing with couples beset by social, economic, and/or

political forces which threaten to disrupt their romantic harmony. The hostile

environments of war and social and economic turmoil function both as an obstacle to his

lovers' happiness and the very condition of their love, against which they must affirm

their feelings for one another. In many of his films, the context of war obstructs the efforts

of young lovers to establish a space for themselves apart from that of the more cynical

and worldly characters around them.

Throughout his career, Borzage denounced war and violence; Liliom ( 1930) condemns

domestic abuse; a profound pacifism underlies A Farewell to Arms ( 1932), and No

Greater Glory ( 1934); and he emerged as one of Hollywood's first and most confirmed

anti-fascists, dramatizing the evils of totalitarian movements in post-war Germany in

Little Man, What Now? ( 1934), and openly attacking fascism well before American entry

into World War II in The Mortal Storm ( 1940).

Borzage's vision is genuinely Romantic in its emphasis upon the primacy and

authenticity of feeling. His lovers emerge as nineteenth-century holdovers in a

dehumanized and nihilistic modern world. The form which Borzage's romanticism most

often takes is a secularized religious allegory. In 7th Heaven, Street Angel, Man's Castle

( 1933), and Little Man, What Now?, his edenic lovers transfrom their immediate space

into a virtual heaven on earth. Chico, the hero in 7th Heaven, dies and is mysteriously

reborn; Angela, the heroine in Street Angel, becomes an angel, a transformation mirrored

in the hero's madonna-like portrait of her. Strange Cargo ( 1940), which was banned by

the Catholic church in several American cities, provides perhaps the most overt religious

allegory. In it, a group of escaped convicts and other outcasts follow a map, written inside

the cover of a Bible, through a tropical jungle. Their 'exodus' concludes with a hazardous

sea voyage in a small open boat and with the miraculous apotheosis of their Christ-like

guide. Borzage's purest lovers appear in Till We Meet Again ( 1944) in which the director

fashions an unstated, repressed romantic liaison between an American aviator shot down

behind enemy lines and the novice from a French convent who poses as his wife in order

to escort him to safety.According to Hervé Dumont ( 1993), Borzage's basic narrative

pattern in his romantic melodramas was that of Mozart's Magic Flute, and involved a

symbolic struggle resembling the rites of passage embodied in the initiation ceremonies

of Freemasonry. Borzage joined the Masion in 1919, eventually rising to the 32nd grade

('Master of the Royal Secret') in 1941. Like Mozart's Sarastro, Borzage oversees the

passage of young lovers through a series of trials and ordeals to achieve a state of spiritual

enlightenment and transformation. Borzage's repudiation of contemporary reality in

favour of an emotional and spiritual inner world proved to be out of step with post-war

American culture. After 1945 he made only four films, and his attempt to retell the great

love story of 7th Heaven to a new generation of filmgoers in China Doll ( 1958) failed to

find a receptive audience. Though various revivals of his films in the United States,

Britain, and France in the 1970s attempted to re-establish his status as a major force in

film melodrama, his work, unlike the more sophisticated and 'modern' cinema of Douglas

Sirk, has yet to achieve the critical recognition it deserves.

JOHN BELTON

SELECT FILMOGRAPHY

Humoresque

( 1920); Lazybones ( 1925);

7th Heaven ( 1927); Street Angel ( 1928); Lucky Star ( 1929); Bad Girl ( 1931); A

Farewell to Arms ( 1932); Man's Castle ( 1933); Little Man, What Now? ( 1934); History

Is Made at Night ( 1937); Three Comrades ( 1938); Strange Cargo ( 1940); The Mortal

Storm ( 1940); I've Always Loved You ( 1946); Moonrise ( 1948); China Doll ( 1958);

The Big Fisherman ( 1959)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Belton, John ( 1974), The Hollywood Professionals.

Dumont, Hervé ( 1993), Frank Borzage: Sarastro à Hollywood.

Lamster, Frederick ( 1981), Souls Made Great Through Love and Adversity.

William S. Hart (1865-1946)

Although born in New York, William Surrey Hart spent his childhood in the Midwest, at a

time when it still retained much of the feel of the frontier. A career on the stage offered

him only a meagre living until he landed the part of Cash Hawkins, a cowboy, in Edwin

Milton Royle 's hit play The Squaw Man in 1905. Parts in other Western dramas followed,

among them the lead in the stage version of Owen Wister's The Virginian in 1907.

Touring California in 1913, he decided to look up an old acquaintance, Thomas Ince, who

was busy developing the studio at Santa Ynez which would soon be known as Inceville.

Ince recognised Hart's potential and offered him work at $175 a week. For the next two

years Hart appeared in a score of two-reel Westerns and a couple of features, working

with the script-writer C. Gardner Sullivan. Typically, as in The Scourge of the Desert,

Hart is cast as a 'Good Badman', frequently an outlaw moved to reform by the love of a

pure woman. In 1915 Ince and Hart joined Triangle Films, and Hart, by now a hugely

successful Western star, graduated finally to feature-length pictures.One of his most

successful Triangle films was Hell's Hinges, released in 1916. Hart plays Blaze Tracy, a

gunman hired by the saloon owner to ensure that the newly arrived preacher does not ruin

his trade by civilizing the town. But Blaze is moved by the radiance of the preacher's

sister. When a mob sets light to the church, he arrives to rescue the girl, and then takes on

the whole town single-handed and burns it to the ground. Hart's tall, lean figure and his

angular, melancholy face projected a persona imbued with all the moral certainties of the

Victorian age which formed him. To villians and to other races, especially Mexicans, he is

implacably hostile. But he is courteous, even diffident, around women. Hart is a loner, his

only companion his horse Fritz.In 1917 Hart moved to Famous Players-Lasky when

Adolph Zukor offered him $150,000 a picture. Distribution of his films under

Paramount's Artcraft label ensured great success in the years immediately after the First

World War. Not all Hart's films were Westerns, but it was the Western to which he

returned time and again. Of Hart's later films still extant, Blue Blazes Rawden ( 1918),

Square Deal Sanderson ( 1919), and The Toll Gate ( 1920) are among the best. Production

budgets increased, and more time and trouble were taken. Those which Hart did not direct

himself were entrusted to the reliable Lambert Hillyer.But as the 1920s progressed, Hart's

films began to appear dated. The pace grew ponderous; Hart, never one for the lighter

touch, took himself more and more seriously, and his tendency towards sentimentality

grew more pronounced. Hart liked to think that his films presented a realistic picture of

the West, and Wild Bill Hickok ( 1923) was an attempt at a serious historical

reconstruction. But Paramount were unhappy with it. Hart was by now 57 years old, and

could no longer present a convincing action hero to the Jazz Age audience. His next

picture, Singer Jim McKee ( 1924), was a flop and his contract was terminated.His last

film, Tumbleweeds ( 1925), released through United Artists, had $100,000 of his own

money in it. It contained some spectacular land rush scenes, but it was another failure and

Hart was forced to retire. Tumbleweeds was reissued a decade later, with a sound-track on

which Hart delivered a spoken introduction: 'My friends, I loved the art of making motion

pictures. It is, as the breath of life to me . . . .' It is an extraordinary moment, fascinating

for the glimpse it offers of a Victorian stage actor in full, faintly ludicrous rhetorical

flight, yet undeniably moving in its evocation of the world of the silent Western which

Hart embodied.

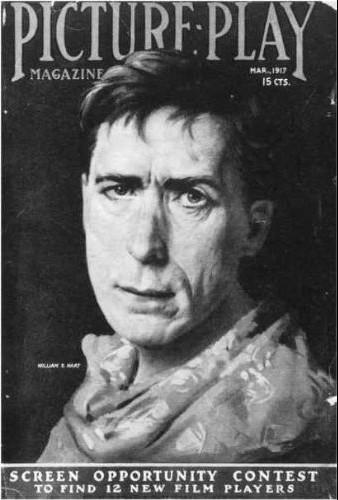

W. S. Hart featured on the cover of

Picture-Play

magazine in 1917

EDWARD BUSCOMBE

SELECT FILMOGRAPHY

In the Sage Brush Country

( 1914); The Scourge of the Desert ( 1915); Hell's Hinges ( 1916); The Return of Draw

Egan ( 1916); The Narrow Trail ( 1917); Blue Blazes Rawden ( 1918); Selfish Yates

( 1918); Square Deal Sanderson ( 1919); The Toll Gate ( 1920); Wild Bill Hickok ( 1923);

Tumbleweeds ( 1925)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Koszarski, Diane Kaiser ( 1980), The Complete Films of William S. Hart: A Pictorial

Record.

Tom Mix (1880-1940)

The most popular Western star of the 1920s, Tom Mix was the epitome of a Jazz Age

movie hero. In place of the moral fervour of William S. Hart, a Tom Mix picture provided

non-stop entertainment, a high-speed melange of spectacular horse-riding, fist-fights,

comedy, and chases. Usually the stunts were performed by Mix himself. In his early

twenties he had worked as a wrangler at the famous Miller Brothers 101 Ranch, a Wild

West show based in Oklahoma. Mix was working with another show in 1909 when the

Selig Company used its facilities to make a film entitled Ranch Life in the Great

Southwest, in which he was featured briefly as a bronco-buster. Over the next seven years

Mix appeared in nearly a hundred Selig oneand two-reel Western, shot first in Colorado

and then in California.In 1917 the Fox sutdio promoted Mix to feature-length films, with

high-quality production values, much of the filming being done on location at spectacular

western sites such as the Grand Canyon. Mix's star persona was a fun-loving free spirit,

adept at rescuing damsels in distress. On screen Tom was clean-living, with no smoking

or drinking, and little actual gun-play. Villains were more likely to be captured by a clever

ruse than dispatched by a bullet. Mix made the occasional foray outside the Western for

example in Dick Turpin ( 1925), but it was the Western that made him, and he in turn

made the Fox sutdio the most successful Western producer of the age. Many of his sixty