The Plantagenets: The Kings That Made Britain (16 page)

Read The Plantagenets: The Kings That Made Britain Online

Authors: Derek Wilson

Tags: #HISTORY / Europe / Great Britain, #Fiction

Prince Edward wintered in Bordeaux and set out the following summer to link up with a force on its way from Normandy that was led by the veteran commander, Henry, Duke of Lancaster (England’s first non-royal duke). However, John the Good had mustered his army at Chartres and prevented the two English contingents from converging. The prince turned back, intending to reach the safety of Gascony, but John intercepted him some 4 miles from Poitiers. The battle fought here on 19 September 1356 pitted Prince Edward’s force of 7,000 men against, probably, a French army of 35,000, and it took place in a difficult terrain of woodland, vineyards, hedges and marsh. It began about eight o’clock in the morning and was all over by midday, save for the pursuit of fleeing horsemen. The English were completely victorious, and the French losses were enormous. More

importantly, however, Edward’s men took a large number of noble prisoners, who would be forced to pay ransom. Just how important ransom was in 14th-century warfare is indicated by Froissart’s account of the capture of King John. The prince sent out riders to a hilltop to see what they could discover about King John: ‘They saw a great host of men-at-arms coming towards them very slowly on foot. The King of France was in the middle of them, and in some danger. For the English and the Gascons … were arguing and shouting out: “

I

have captured him,

I

have.” But the king, to escape from this danger, said: “Gentlemen, gentlemen, take me quietly to my cousin, the Prince, and my son with me: do nor quarrel about my capture, for I am such a great knight that I can make you all rich.”’

4

1357–68

With two rival kings in captivity, Edward III was in an excellent bargaining position, but either he overplayed his hand or he had no intention of reaching a negotiated settlement. He demanded a ransom of 4 million écus and control of all of western France, from the Channel to the Pyrenees, in return for renouncing his title to the throne. His terms having been rejected, he invaded France again in 1359 and made straight for Rheims in order to be crowned in the traditional coronation place of French kings. Finding the city too well defended, he lifted the siege in January 1360 and went instead on a raid through Burgundy. He was hoping for another decisive battle, but a severe winter took

so much toll on his army that he was obliged to open talks again. After much haggling, King John’s ransom was reduced to 3 million écus and Edward renounced his claim to all French territory except Calais and Aquitaine and neighbouring territory, but the issue of sovereignty over disputed lands was left on hold. This vague settlement was ratified by parliament in January 1361.

This year the plague returned, although not as seriously as 13 years previously, and from this point a noticeable change in Edward’s behaviour was noticed. The vigour and decisiveness of earlier years was gone, and it seems that the king’s mental faculties were failing. His decline coincided with the accession of a new and talented king in France. Charles V ascended to the throne in April 1364 on the death of his father, and he was bent on reversing the humiliation Edward had inflicted on his country and his family.

Edward was now more inclined to pursue peaceful means to obtain control of Scotland. David II had been released in 1357 on agreeing to pay a large ransom in annual instalments. This was a great burden on the Scots, and Edward hoped to negotiate acceptance of his sovereignty in return for cancelling the debt. In November 1363 David, who was still childless, agreed to try to persuade his countrymen to convey the crown to Edward and his heirs after his own death. In return, Edward would cancel the ransom and restore those parts of Scotland he controlled. But the Scottish nobles would have none of this deal, and at the same time Charles V, instead of formally relinquishing his claim to Aquitaine, as required

by the vague 1361 treaty, looked for a reason to occupy the territory. The ageing king could see no end to his two major problems.

1369–77

The summer of 1369 was disastrous for Edward III. Charles devised an excuse to renew the war and sent troops into Aquitaine. In response, Edward hurriedly summoned parliament and secured a vote of taxes. That done, he revived his claim to the French crown and began assembling his troops. It was at this point, just as he was preparing to cross the Channel at the head of his army, that personal tragedy struck. ‘The good queen of England that so many good deeds had done in her time, and so many knights succoured, and ladies and damosels comforted, and had so largely departed of her goods to her people, and naturally loved always the nation of Hainault where she was born; she fell sick in the Castle of Windsor, the which sickness continued in her so long that there was no remedy but death.’

5

The king had already formed an attachment for a mistress, Alice Perrers, but there is no evidence of a serious estrangement between Edward and Queen Philippa. From this point, Alice exercised a growing and disastrous influence over the monarch. In 1370 the Prince of Wales, who was organizing the defence of Aquitaine, fell ill. From a litter he oversaw the long siege of Limoges, and when it fell he ordered the execution of 3,000 inhabitants – men, women and children – then fired the city. But such fearsome demonstrations could not

stave off defeat. The year 1372 was one of military disasters. Charles V overran much of Aquitaine, and an English fleet was defeated in the Channel. Edward’s fourth son, John of Gaunt, who had been created Duke of Lancaster in 1361, was sent to aid England’s ally, the Duke of Brittany, but instead went on a looting expedition in eastern France. He and the Black Prince were at loggerheads and vying for influence with their father. In August King Edward took ship with his army for another campaign in France but weeks of foul weather prevented him making a landing and he was forced to return home. In 1375, Pope Gregory XII mediated a truce, agreed at Bruges, between Edward and Charles. It was a humiliating climb-down after years of spectacular success, and it was very unpopular with England’s leading men.

By 1376 the Treasury was drained dry, and the government was forced to summon parliament in April. This assembly, which was held from 28 April to 10 July, became known as the ‘Good Parliament’ because, in the name of the people, the Commons attacked court corruption and maladministration. The king no longer enjoyed the respect that he had had in his heyday because, as was widely known, he was now completely controlled by Alice Perrers and John of Gaunt, both of whom were unpopular. The new parliament was determined to clean up the government, and they stripped the council of those advisers they did not like and had Edward’s mistress sent away from court. By withholding funds they imposed new councillors on the king.

The only member of the royal inner circle who still commanded respect was the Black Prince, but in June he died.

Lancaster and his friends at court lost no time in dismissing the Good Parliament. They removed the new councillors from office and imprisoned one of the parliamentary ringleaders. Alice Perrers was allowed back to court.

By the end of September Edward’s body, like his mind, was failing. He survived through the autumn and winter and was able to attend the Garter ceremony in April 1377, but he died on 21 June, probably of a stroke.

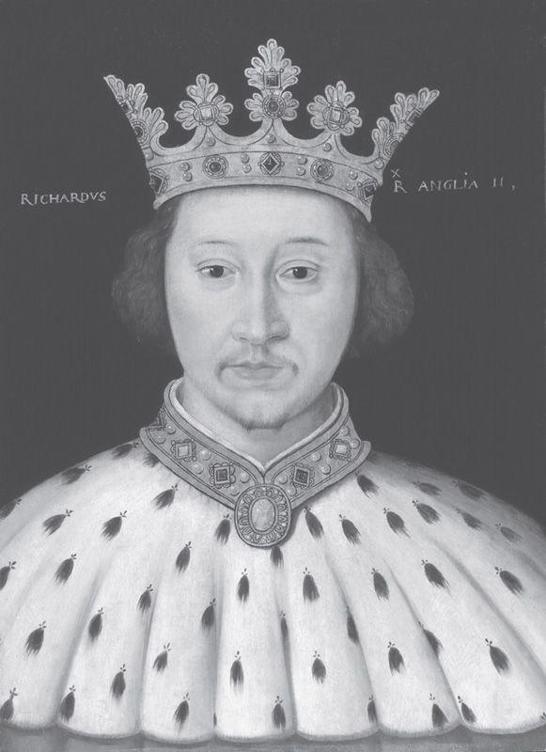

RICHARD II 1377–99

The social dislocation caused by repeated visitations of the plague provides the backdrop to this troubled reign. In 1400 the population was less than half what it had been before the Black Death, and the economic hardship and psychological malaise felt at all levels of society led to the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 and to the emergence of Lollardy, the ‘English heresy’, in the 1390s. To these disturbances were added unfinished business in Scotland and France, renewed conflict between king and parliament, and the challenge for the crown of John of Gaunt and, later, John’s son, Henry Bolingbroke. Richard’s fate – deposition and murder – echoed that of his great-grandfather.

1377–80

Richard became king at the age of ten because both his father, the Black Prince, and his elder brother, Edward, had died. On 16 July 1377 the boy king rode in a splendid procession through London to Westminster Abbey for his coronation, thus establishing a custom that was to be maintained for 300 years. The solemn and lengthy service may well have instilled into the boy a profound sense of the sacredness of monarchy, but he had inherited a country whose international reputation had declined over the previous decade and whose diminished population was weighed

down with war taxes and rising prices. In February 1377 a cash-strapped government had imposed, for the first time, a universal poll tax, which brought more people than ever before within the scope of revenue collection.

Only weeks after the coronation a French raid on the south coast from Rye to Plymouth demonstrated England’s vulnerability and military weakness. The attackers landed at several points, looting at will, and they burned Hastings and captured the prior of Lewes to hold him to ransom.

No official regent was appointed, though two of his father’s trusted companions, Sir Simon de Burley and Sir Aubrey de Vere, were appointed as knights of the household to guide the boy king. John of Gaunt, Richard’s uncle, who had dominated the political scene since the death of the Black Prince, took no official position in government, largely because of the opposition of parliament, but the king looked to him for support and guidance, and Lancaster was thought of – rightly – as the leading political figure in the country. Richard, though young, was regarded as possessing full royal power, but parliament claimed the right to appoint a council to assist him. Another factor in the dynamic of government was the king’s household. Richard was, in practice, dependent on his day-to-day companions, who came to be regarded with suspicion as ‘favourites’. Among them was Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford, who was probably introduced to the court by his uncle, Aubrey, and who later emerged as Richard’s closest friend. The supervisory councils were unable to exercise effective control over the expenditure of the royal household, which, from an early date, was regarded as excessive.

In 1380 parliament decreed an end to the councils that had been its own creations, and it was this muddled constitutional situation that contributed to Richard’s development of extreme opinions about the sacred nature of kingship and the absolute power wielded by the monarch.

1381

In the aftermath of the Black Death the ecclesiastical hierarchy had lost much of the respect traditionally accorded to it and widespread indignation was directed at every level of the priesthood. The papacy itself was in turmoil. From 1309 to 1378 the popes resided at Avignon as protégés of the French kings (with whom England was at war), and the following years, 1378–1417, were known as the ‘great schism’ because rival popes, based at Rome and Avignon, competed for the loyalty of Christian Europe. Wealthy bishops and abbots were resented for their ostentation and their unwillingness to share the financial burdens placed upon laymen, and many parish priests had not been forgiven for deserting their flocks during the plague years.

Fundamental to the general discontent was a widely held belief that the clergy were more interested in collecting their tithes and taxes than in fulfilling their responsibilities or setting a moral example. At the same time, there existed among many lay people a desire for a deeper, personal spirituality. John Wyclif (

c

.1330–84), an Oxford scholar and preacher, attacked the church hierarchy in his lectures and sermons and attracted the attention of John of Gaunt, who

was campaigning against the interference of Rome on English affairs. The duke found Wyclif a valuable ally and encouraged his anticlericalism. This was the background to the emergence of what has been called the ‘English heresy’, Wycliffism or Lollardy.

In February 1377 the Bishop of London ordered John Wyclif to be examined in St Paul’s Cathedral on the content of his recent sermons. The Duke of Lancaster turned up to support his preacher, got into a furious row with the bishop and threatened to drag him down from his throne by the hair. Thus protected, Wyclif developed his beliefs in greater detail. He began to consider the doctrinal basis of the church’s institutions and to question their validity. Fundamentally, Wycliffism was all about

authority

. The scholar began by reflecting on the relationship between church and state and ended by rejecting the claims of the church’s hierarchy not only to temporal authority but also to spiritual authority. The power wielded by the clergy over the laity was based on their sacerdotal function as mediators between man and God.

Priesthood set men apart from their neighbours by virtue of their ability to ‘make God’ in the mass, to hear confession and to pronounce absolution. Wyclif rejected these claims in a series of books. For the authority of the ‘Bishop of Rome’ (as Wyclif called the pope, to indicate that he had no authority in England) he substituted the Bible. ‘All Christians, and lay lords in particular, ought to know holy writ and to defend it,’ he wrote in his treatise

On the Truth of Holy Scripture

(1387). ‘No man is so rude a scholar but that he may learn the words of the Gospel.’ But the only Bible available

in England was the Vulgate, written in Latin and accessible only to scholars and a minority of educated clergy.