The Rape of Europa (37 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

The Tchaikovsky Museum: scores and motorcycles

By late summer the SS Special Commandos had visited Minsk and removed the cream of the city’s collections. The local Reichskommissar, Wilhelm Kube, a Rosenberg appointee, wrote to his chief expressing anger that “Sonderführer whose names have not yet been reported to me” had taken so much without his permission, and dismay that the SS, once their mission had been completed, had left what remained to “the Wehrmacht for further pillaging.” A handwritten notation on this letter by Rosenberg reveals that the order to remove the Minsk treasures had come from Hitler himself. So much for the Eastern occupation chief’s decree that everything should be left in place.

13

Rosenberg’s idea of preserving Ukrainian culture and nationalism in order to turn the people against Stalin was also no match for the suicidal racial fanaticism of Hitler and Himmler. Kiev would be proof of that. After its fall on September 17 its museums, scientific institutes, libraries, churches, and universities were taken over to be exploited and stripped. Everywhere in the USSR special attention was given to the trashing of the

houses and museums of great cultural figures: Pushkin’s house was ransacked, as was Tolstoy’s Yasnaya Polyana, where manuscripts were burned in the stoves and German war dead were buried all around Tolstoy’s solitary grave. The museums honoring Chekhov, Rimsky-Korsakov, and Tchaikovsky received similar attentions, the composer of the 1812 Overture being particularly honored by having a motorcycle garage installed in his former dwelling.

In early October 1941 Hitler, anxious to finish with the USSR, launched a great offensive toward Moscow and ordered simultaneous assaults on Leningrad and the Black Sea coast and oil fields. The Luftwaffe, from its forward bases, was now able to fly missions aimed at the destruction of Russian industrial targets far into the Soviet heartlands. One such target was Gorky, which sheltered not only part of the collections of Pavlovsk and Peterhof, but those of Leningrad’s Russian Museum and many others, all of which would have to be moved once more. The icons, pictures, and folk art of the Russian Museum went six hundred miles east to Perm by the undesirable method of river barge.

This time the Pavlovsk curators decided to be truly safe and remove their things to Tomsk in Siberia, fourteen hundred miles away. The final departure of the train, loaded amid air raids, was delayed for hours awaiting the arrival of the families and children of museum personnel who had been unable to find a passable route to the station. On November 8, in the midst of an air attack, the train, pulling twenty cars of works of art, crossed the Volga on the last remaining bridge and headed to the east. While the German offensive continued, railroad workers hid the art-laden cars on a siding deep in the forests for two weeks to wait out the bombings. Late one December night they arrived in Tomsk, where the temperature stood at −55 degrees centigrade. But there was no room in this frozen town, and the weary train went on to Novosibirsk, which also sheltered Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery. There the curators were given the town’s theater for storage.

The care of works of art in this climate presented unusual problems. The 402 crates were piled up outside the station, covered by tarpaulins and canvas scenery from the theater. Everything was moved to the new quarters on horse-drawn sleds guided by women from Leningrad still in their light city clothes and shoes. Once in the theater, the crates had to be gradually acclimatized in order to avoid condensation on the objects. This was done by first lowering and then gradually raising the temperature of the vestibule by alternately opening and closing windows and doors. The process took three weeks. The guardians and their families would live for two long years in the basement below. Despite the cold and the terrible

food, being museum people, they soon organized exhibitions from their holdings to maintain morale and pass the long months of waiting.

14

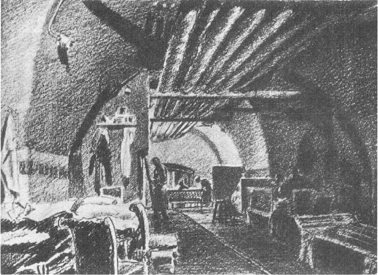

Life under siege in the basements of the Hermitage (Drawing by Alexander Nikolsky)

In Leningrad the wells of courage would be more deeply plumbed. After the rail lines had been cut, Hermitage curators continued to pack and move things into the vast cellars of the complex of palaces. Smaller museums brought their holdings in. And alongside the works of art in the bombproof cellars lived a colony of some two thousand souls. During the continuing siege these subterranean spaces became a center of intellectual resistance and survival. As the winter came on, half-frozen art historians, poets, and writers worked on their research projects. Architect Alexander Nikolsky kept a visual diary of the eerie empty spaces of the vast museum in which occasional candles flickered. Only one room had electricity and a little heat, supplied by the generators of the

Pole Star

, a large yacht, once the property of the Czars and now taken over by the Navy, which was tied up to the quay in front of the Winter Palace.

Hermitage director Orbeli was undaunted. Determined to carry on as usual, he refused to cancel a long-planned program to honor the Samarkand poet Alisher Navoi. Printed invitations went out, and half-starved

participants left their fortifications and trenches to make their way through deep snow and falling bombs to the event. It was a great success. But daily the terrible cold increased and the food supply diminished. Only a thin lifeline of supplies could be brought in to Leningrad’s 3 million residents on the “Road of Life,” which crossed the frozen waters of Lake Ladoga. It could not save them all: in December 1941 alone more than fifty thousand died of starvation. People ate remarkable things: in the Hermitage conservators produced a jellied soup made of carpenter’s glue. Soon the museum had its own infirmary for the starving and a mortuary below the library, where frozen corpses stayed for weeks until they could be removed for burial. And the shelling continued. Upstairs in the echoing palace, security was provided by a team of forty or so not-so-young ladies, who did their best to cover shell holes on the windswept roofs with sheets of plywood and deal with the snow which swirled through the shattered windows into the ice-coated galleries.

Spring brought some relief to human beings but only made things worse in the unheated museum, where thawed pipes burst and flooded the basements, forcing weakened curators to wade about to retrieve floating pieces of Meissen. Mildew blossomed on silk furniture which had to be moved out into the sun next to the vegetable gardens being planted in every available space. The only objects completely unaffected were the well-embalmed Egyptian mummies and the prehistoric remains taken from the Siberian permafrost. The siege did not end during this spring, but went on for nearly two more years. In the first three months of 1943 alone, as the bombing continued, the staff would remove, by hand, eighty tons of mixed glass, ice, and snow, much of which had to be chipped off the mosaics and parquet floors with crowbars. The thirtieth, and last, bomb would not fall on the Hermitage until January 2, 1944, twenty-five days before Leningrad was liberated.

15

Hitler was surprised that the Soviet Union did not succumb in the five months he had allocated for its conquest. By late November 1941, as the famous Russian winter took hold, his armies, still dressed in their summer uniforms, were being pushed back from Moscow by fresh, fur-clad troops from Siberia. The Führer had done better in the south, where he now held most of the Ukraine and the Crimean peninsula, and had laid siege to Sevastopol. It was impressive, but not enough for Hitler. No retreat was allowed in the Moscow region. He would not imitate Napoleon, but would hold the line, and finish the job in the spring.

While the miserable, freezing German armies, obeying their Commander in Chief, struggled to maintain their northern positions, their more

comfortable colleagues in the south were busily setting up an occupation government and the planned “cultural” institutes. Safeguarding efforts quickly expanded. Here they did not have to worry about clearing out the houses of the nobility. This Stalin had conveniently done for them, but there was still plenty to do. Objects in private hands were seized or easily obtained by intimidation or barter. One SS officer reported to Himmler that he was sending along “several antique finds (agate necklaces, bronze figures, pearls, etc.) bought from the widow of deceased archaeologist Prof. Belaschovski, Kiev, for 8 kilograms of millet.”

16

By now the SS Ahnenerbe and the ERR had joined the Special Commandos in gathering the spoils. Rosenberg, still determined to establish his ascendancy, had obtained a directive from Hitler on March 1, 1942, again ordering all agencies to cooperate with him in his confiscation of Jewish and Masonic items. Logistical support would be supplied by the Wehrmacht. This agreement left two large loopholes: it neither limited the powers of the SS nor gave the ERR any right to “safeguard” museum holdings or archaeological finds.

17

In these areas the Ahnenerbe had moved right in. As early as July 1941 this archaeological wing of the SS had urged “action in South Russia” by a group to be headed by SS Sturmbannführer Professor Herbert Jankuhn of Kiel. By February of the next year they had proposed such genteel activities as “research into the finds and monuments of the Gothic Empire of Southern Russia,” Jankuhn’s speciality. Somewhat less highbrow were projects to safeguard the holdings of the Museum of Prehistoric Art in the Lavra Monastery near Kiev, and those of “the destroyed museum at Berdichev.” Jankuhn later claimed to be acting in the spirit of the absent Kunstschutz; but the fact that he continually removed museum collections to SS Collecting Points and thence to Germany gives the lie to his claim of altruism. All this was approved by Himmler, who attached Jankuhn’s special detail to his Waffen SS Division “Viking,” which was to give it “every support possible.”

18

Other special details were proposed for the Crimea and the Caucasus. The Nazis had great plans for this sunny region. Himmler’s intellectuals envisioned the Crimea as suitable for resettlement by ethnic Germans. (Hitler, musing at his headquarters, said that although the newly conquered island of Crete was nice, it was not easily accessible, but that an autobahn could be built to the Black Sea resorts to assuage the eternal Germanic quest for the sun.

19

) Meanwhile, the Ahnenerbe began shipping valuables back not only for study in Berlin but to decorate Wewelsburg, Himmler’s own luxurious schloss and SS spa, where stressed officers were waited on by the inmates of a nearby concentration camp.

Rosenberg was very unhappy with these arrangements. During the spring and summer of 1942 he vainly sent out further directives ordering that all “safeguarding” be cleared with the ERR, and that all seizures which had already taken place be reported to his staff. It was not until the end of September 1942 that he managed to have museum collections added to his authorized field of activity. This only increased the competition. One SS operative who had cleared out a cache before the arrival of his compatriots triumphantly reported home that “a Dr. Brennecke of the ERR showed up at Armavir. As the museums had already been confiscated by the SS, his excursion had no results.” Himmler’s men were not good sports when outmaneuvered: arriving too late at another site, they complained that the ERR had “taken hold of the Crimea and confiscated everything” so that it was “impossible for the Ahnenerbe to work there.”

20

What was not removed by these specialists, despite Rosenberg’s imprecations, continued to be available to the Wehrmacht and its camp followers. Entrepreneurs brought in to make the conquered territories livable for their countrymen soon had a thriving black market under way. This was often too much even for their colleagues. A building contractor from Munich was formally accused by his co-workers of taking home paintings and sculpture from the Museum of Rovno, seat of the military government for the Ukraine. He had also falsified ration cards for food and tobacco and traded army gasoline for “eggs and cognac from the natives.”

21

This sort of grazing was rampant at all levels. Even Goebbels was shocked by the corruption, confiding to his diary, “Our Etappe [support] organizations have been guilty of real war crimes. There ought really to be a lot of executions to reestablish order. Unfortunately the Führer won’t agree to this.” The “war crimes” were not atrocities, but the action of the Etappe troops, who, when they retreated, had “abandoned tremendous quantities of food, weapons, and munitions” in favor of “carpets, desks, pictures, furniture, even Russian stenographers, claiming these were important war booty. One can imagine what an impression this made on the Waffen SS.”

22

Other books

Erotic Deception by Karen Cote'

The Last Magician by Janette Turner Hospital

Blood Moon by Ellen Keener

Queen of Hearts (The Crown) by Oakes, Colleen

Lost Light by Michael Connelly

Pure Blooded by Amanda Carlson

Furever: BBW Paranormal Shapeshifter Romance by Kate Kent

CLOSE TO YOU: Enhanced (Lost Hearts) by Dodd, Christina

Lady Viper by Marteeka Karland

The Knife That Killed Me by Anthony McGowan