The Rape of Europa (41 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

Clark and Maclagan were correct in thinking that the British Army would handle any monuments problems by itself. But in pooh-poohing the usefulness of “an official archaeologist at GHQ” they proved less than clairvoyant, for it was none other than the famous archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley, excavator of the tombs of the Sumerian kings at Ur in Iraq, who would eventually be appointed Archaeological Adviser to the War Office—but not until October 1943. The evolution of this post took some years, and was in the best British tradition of muddling through.

British forces had occupied Cyrene, on the coast of Libya, for several months in early 1941. At the time Libya was one of the jewels of Mussolini’s new Roman Empire. The Duce had spent a great deal to restore classical ruins at Leptis Magna, Cyrene, Sabratha, and other sites all along the Mediterranean. This was not always done with archaeological accuracy in mind. Woolley later commented that “scientific research was throughout made subordinate to, or more often was altogether abandoned in favor of, theatrical display; but no visitor could fail to be struck by the imposing effect of the excavations, and to the Italian Fascist they did indeed symbolise the glories of his traditional ancestry.”

The Italians retook the area late in the spring of 1941, and by summer had produced a pamphlet with the accusatory title

What the English Did in Cyrenaica

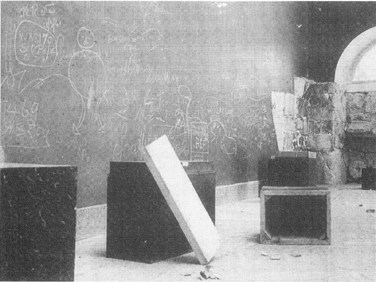

, illustrated with pictures of smashed statues, empty pedestals, and rude Anglo-Saxon graffiti, all allegedly the work of Commonwealth troops. These later turned out to be falsifications—the statues were in the Italians’ own repair shops, and the graffiti, though authentic, were not on monuments. But the propaganda effects were unpleasant, and resulted in an “anxious interchange of messages between the War Office in London and GHQ, Middle East.” After the nearest available archaeologist—who happened to be Woolley, stationed at the War Office on quite unrelated duty—was consulted, orders were sent to Montgomery’s forces, just beginning the campaign for El Alamein, to preserve “any archaeological monuments which might come into their possession.”

How exactly this was to be done, and where the monuments were located,

was not specified. Taking this to heart, British soldiers quickly secured the museums and sites in Cyrene when it was recaptured. But control was more difficult at remoter sites, where, as soon as the fighting stopped, off-duty troops began carving their names in the stones, chipping away at bas-reliefs for souvenirs, and obliterating fragile mosaics by driving vehicles across them.

Italian propaganda photograph showing alleged Allied vandalism in Cyrene: Only the graffiti is genuine.

Fortunately for posterity, one of the first officers on the scene was Lieutenant Colonel Mortimer Wheeler, archaeologist and director of the London Museum, who reported these problems to his superiors and was immediately put in charge of protection. Equally lucky was the presence of another former London Museum curator, Major J. B. Ward-Perkins, who was able to help Wheeler supervise this enormous area. Totally in their element, the two officers soon had the Italian custodians and Arab guards, who had been found hiding in the museum at Sabratha, back at work under the watchful eye of a British NCO.

A little guidebook was printed up and both informative and warning signs were posted in the ruins. There were lectures and tours. Woolley wrote that this educational effort had been so successful that “when troops

digging a gun position in the sandhills east of Leptis came upon a Roman villa with well preserved frescoes they carefully cleared out the ruins, made a plan of the building, photographed the frescoes and filled the site in with sand, to secure its protection, before shifting their gun pit to a new position.” The archaeologists surveyed all the sites and straightened out the Italian photo archives. For their own later use they carefully saved the aerial photographs utilized by Intelligence officers. All this activity was formalized in the ex post facto tradition of occupying armies by a “Proclamation on Preservation of Antiquities” issued on November 24, 1943, which defined the rights over antiquities vested in the British Military Administration, and forbade “the excavation, removal, sale, concealment or destruction of antiquities without license.” A British Monuments officer remained in North Africa until occupation troops departed.

23

Woolley at home and the officers in the field were supported in these activities by consultations with the private sector. Experts from such institutions as the Greco-Roman Museum in Alexandria and the Institute of Archaeology in London were called in to inspect sites or offer advice. There seemed no need for anything more, and American urgings for a high-level commission met with little enthusiasm. Indeed, the “establishment strength” of the Archaeological Adviser’s branch consisted, rather cosily, of “the Adviser himself, Lady Woolley, and a clerk.” Its motto, suitably classical, was taken from Pericles’ funeral oration, and, roughly translated, read, “We protect the arts at the lowest possible cost.” Woolley soon learned to avoid Army channels: “The Adviser might have his own views as to how something ought to be done and though aware that those views might not be well adapted to local conditions, wished that they might at least be taken into consideration; or he might require information not contained in the reports sent to him. For the most part, this could only be done by an interchange of demi-official letters, and whereas official communications passed through regular channels were relatively few, the ‘D.O.’ letter file was voluminous.”

24

The need for a detailed scenario for Sicily, the establishment of an office specifically designed to respond to civil affairs initiatives, the lobbying efforts of all parties, and the actual example of a British operation, all suddenly combined in the spring of 1943 to make the idea of the protection of monuments and works of art acceptable on the American home front. The problem would now be to weave the strands together into a single line of action; the lack of communication among the interested parties would make this unbelievably difficult and contrast vividly with the German confiscation effort so carefully directed from the pinnacles of Nazi power.

The first spark of response on art protection in Washington came on March 10, 1943, when Colonel James H. Shoemaker wrote to American Defense Harvard that he could guarantee that “information covering this area will be included in the data to be used by Military Administrative officials in occupied areas.” He would, “therefore, appreciate the cooperation of Dr. G. L. Stout in providing us with information covering this matter. It would be helpful if, in the more important cases, we could have a paragraph indicating the significance of the item in question to the local population. Without this it would be difficult to exercise judgment in respect to the importance of action in any given case.”

25

What this innocuous-sounding request meant to art historians was a series of lists of every important church, statue, building, and work of art for each country likely to be occupied, with justifications for the preservation of same. And it was wanted by July.

Within days the gap between academe and the military began to show. Colonel Shoemaker, responding to a rather flowery draft for the introduction of the proposed manual and lists, diplomatically suggested that “long range concepts” might be “pushed into the background” by “the pressure of immediate considerations.” The Army, in other words, was not interested in art for art’s sake.

In the same letter he wrote that research laboratories might be included in the lists of museums and libraries, as it “would focus attention on this subject more sharply if all of these items could be presented together in a well integrated way.” Shoemaker had clearly foreseen that the U.S. government would make great efforts to obtain and preserve technology and research which might be of future use. Personnel officers, he indicated, would also respond more easily to assigning men with special expertise to such work if “research laboratories” were included—he could not very well say that most of the federal government did not give a hoot about art. This hint of cooperation with the scientific community was ignored by the art group, a bit of chauvinism which would cost them dearly.

As to the exact areas to be covered by the monuments lists, the wily Colonel, following Combined Chiefs of Staff orders to keep plans very general, merely said that he did not think the committee should feel “any restrictions,” as “we wish to avoid arousing any critical reactions on the part of friendly governments in exile.” The material should be “in distinctly separate units by countries.” Anything which might reveal where the armies were headed next would be disastrous.

26

In early April, Shoemaker again wrote to American Defense Harvard to say that approval had been given for “the commissioning of a few men with special competence in this field for training in military government.”

27

By now the technical manual compiled with the collaboration of Stout was virtually complete, and work had begun on the lists of monuments and collections and general cultural background material for the handbooks on each country, which were to be given to units in the field.

Within days of receiving Shoemaker’s first letter, American Defense Harvard had sent out a barrage of letters asking for such information from prominent exiles living in the United States. Among them were Sigrid Undset, the Nobel Prize-winning novelist, for Norway; Jakob Rosenberg, the eminent Rembrandt scholar, for Holland and Belgium; and Georges Wildenstein for France. Paul Sachs was not pleased at the last choice, but Wildenstein so strongly resisted efforts to limit him to making lists only of art-oriented refugees—not objects—that Sachs discreetly dropped his objections. Now letters were sent to institutions all over the country asking the whereabouts of already drafted personnel suited to “monuments” training. Shoemaker, perhaps unsettled by the speed of these efforts, wrote to warn that “very few persons will be needed in this field. The number would necessarily be limited. To overdo the matter would cause it to boomerang.”

28

Another, parallel approach, on March 15, by Taylor and Archibald MacLeish to Secretary of War Stimson had also fallen on fertile ground. Their memoranda had been referred to Colonel John Haskell, the acting director of the brand-new Civil Affairs Division, who considered the idea important enough to recommend that it immediately be studied by the Operations Division, the highest-level planning group of the War Department.

29

He was supported in this by General Wickersham, chief of the School of Military Government, who recommended on April 1 that “the Civil Affairs section of each theater commander include one or two experts to assist and advise in the matter of protecting and preserving historical monuments, art treasures and similar objects.” Haskell also recommended that a pool of thirty specialists and technicians in the field be formed to be available when needed, and that language on art protection be included in the Army field manual. On April 19 he met with the officers of the National Gallery, who also agreed to provide names of qualified experts. The Civil Affairs Division heard for the first time at this meeting of the proposal for a Presidential commission, and thought it sound. Four days later, over Marshall’s signature, a cable went to Eisenhower to ask if he would agree to the addition of two staff advisers on fine arts, one British and one American, to the table of organization for HUSKY. His affirmative reply was received on April 25.

30

By May the material for the handbooks had begun to reach Colonel Shoemaker. Sachs’s doubts about Wildenstein’s contribution were now

confirmed. Shoemaker, with the utmost delicacy, pointed out that there was a certain amount of talking down in the tone of the reports. In the French draft, for example, it appeared superfluous to say:

Occupying authorities should respect, and make their men respect, the

classé

buildings. They will

almost invariably

find a local savant willing to explain and arrange excursions to visit these buildings; and such visits can only have a good effect, by making the old buildings more interesting to officers and troops. Attackers should, if possible, avoid obliterating entire towns. The French naturally resent the German habit of destroying everything when they leave. They will equally resent any American habit of destroying everything before arrival, if such a habit develops.

With American armies massing in North Africa for the invasion of Sicily after the grueling campaign in the desert, Shoemaker dryly noted that there would doubtless come a time for sightseeing, but that under present conditions “instructions in respect to this will appear rather ironic to officers … the advice in the remainder of the paragraph will also appear gratuitous to them.” He concluded, with some irritation, “A line should also be drawn between practical instructions for the conservation of objects and general instructions regarding the conduct of the Army (which should be excluded).”

31

Stout gleefully reported that he had heard rumors that “the [art] historians have been going a little pedagogical with the U.S. Army. That of course is a waste of time.”

32

The Cambridge Committee quickly sent off a firm set of rules urging moderation on its compilers, hoping to soothe any ruffled academic feathers with the comment that “the Committee is sure you will understand that the preparation of this material is in some degree experimental.”

33

Other books

Love You Better by Martin, Natalie K

Changed by His Son's Smile by Gianna, Robin

Jack Pierce - The Man Behind the Monsters by Essman, Scott

A Wilder Rose: A Novel by Susan Wittig Albert

Angel Train by Gilbert Morris

The Love Killings by Robert Ellis

Just A Woman (Marina: Part Two: Naughty Nookie Series) by Akeroyd, Serena

The Last Christmas by Druga, Jacqueline

After Hannibal by Barry Unsworth

The Jungle Books by Rudyard Kipling, Alev Lytle Croutier